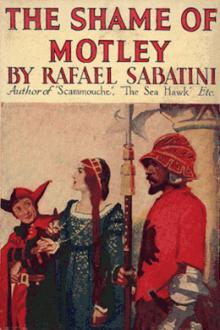

The Shame of Motley by Rafael Sabatini (the reading strategies book txt) 📖

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: -

Book online «The Shame of Motley by Rafael Sabatini (the reading strategies book txt) 📖». Author Rafael Sabatini

Anon an elephantine trumpeting of laughter seemed to set the air a-quivering. Ramiro was lying back in his chair a prey to such a passion of mirth that it swelled the veins of his throat and brow until I thought that they must burst—and, from my soul, I hoped they would. Adown his rugged cheeks two tears were slowly trickling. The Lord Filippo, as presently transpired, had been telling him of the epic I had written in praise of the Lord Giovanni’s prowess. Naught would now satisfy that ogre but he must have the epic read, and Filippo, who had retained a copy of it, went in quest of it, and himself read it aloud for the delight of all assembled and the torture of myself who saw in Madonna Paola’s eyes that she accounted the deception I had practised on her a thing beyond pardon.

Filippo had a taste for letters, as I think I have made clear, and he read those lines with the same fire and fervour that I, myself, had breathed into them two years ago. But instead of the rapt and breathless attention with which my reading had been attended, the present company listened with a smile, whilst ever and anon a short laugh or a quiet chuckle would mark how well they understood to-night the subtle ironies which had originally escaped them.

I crept away, sick at heart, while they were still making sport over my work, cursing the Lord Giovanni, who had forced me to these things, and my own mad mood that had permitted me in an evil hour to be so forced. Yet my grief and bitterness were little things that night compared with what Madonna was to make them on the morrow.

She sent for me betimes, and I went in fear and trembling of her wrath and scorn. How shall I speak of that interview? How shall I describe the immeasurable contempt with which she visited me, and which I felt was perhaps no more than I deserved.

“Messer Biancomonte,” said she coldly, “I have ever accounted you my friend, and disinterested the motives that inspired a heart seemingly noble to do service to a forlorn and helpless lady. It seems that I was wrong. That the indulging of a warped and malignant spirit was the inspiration you had to appear to befriend me.”

“Madonna, you are over-cruel,” I cried out, wounded to the very soul of me.

“Am I so?” she asked, with a cold smile upon her ivory face. “Is it not rather you who were cruel? Was it a fine thing to do to trick a lady into giving her affection to a man for gifts which he did not possess? You know in what manner of regard I held the Lord Giovanni Sforza so long as I saw him with the eyes of reason and in the light of truth. And you, who were my one professed friend, the one man who spoke so loudly of dying in my service, you falsified my vision, you masked him—either at his own and at my brother’s bidding, or else out of the malignancy of your nature—in a garb that should render him agreeable in my eyes. Do you realise what you have done? Does not your conscience tell you? You have contrived that I have plighted my troth to a man such as I believed the Lord Giovanni to be. Mother of Mercy!” she ended, with a scorn ineffable; “when I dwell upon it now, it almost seems that it was to you I gave my heart, for yours were the deeds that earned my regard—not his.”

Such was the very argument that I had hugged to my starving soul, at the time the things she spoke of had befallen, and it had consoled me as naught in life could have consoled me. Yet now that she employed it with such a scornful emphasis as to make me realise how far beneath her I really was, how immeasurably beyond my reach was she, it was as much consolation to me as confession without absolution may be to the perishing sinner. I answered nothing. I could not trust myself to speak. Besides, what was there that I could say?

“I summoned you back to Pesaro,” she continued pitilessly, “trusting in your fine words and deeming honest the offer of services you made me. Now that I know you, you are free to depart from Pesaro when you will.”

Despite my shame, I dared, at last, to raise my eyes. But her face was averted, and she saw nothing of the entreaty, nothing of the grief that might have told her how false were her conclusions. One thing alone there was might have explained my actions, might have revealed them in a new light; but that one thing I could not speak of.

I turned in silence, and in silence I quitted the room; for that, I thought, was, after all, the wisest answer I could make.

Despite Madonna Paola’s dismissal, I remained in Pesaro. Indeed, had I attempted to leave, it is probable that the Lord Filippo would have deterred me, for I was much grown in his esteem since the disclosures that had earned me the disfavour of Madonna. But I had no thought of going. I hoped against hope that anon she might melt to a kinder mood, or else that by yet aiding her, despite herself, to elude the Borgia alliance, I might earn her forgiveness for those matters in which she held that I had so gravely sinned against her.

The epithalamium, meanwhile, was forgotten utterly and I spent my days in conceiving wild plans to save her from the Lord Ignacio, only to abandon them when in more sober moments their impracticable quality was borne in upon me.

In this fashion some six weeks went by, and during the time she never once addressed me. We saw much during those days of the Governor of Cesena. Indeed his time seemed mainly spent in coming and going ‘twixt Cesena and Pesaro, and it needed no keen penetration to discern the attraction that brought him. He was ever all attention to Madonna, and there were times when I feared that perhaps she had been drawn into accepting the aid that once before he had proffered. But these fears were short-lived, for, as time sped, Madonna’s aversion to the man grew plain for all to see. Yet he persisted until the very eve, almost, of her betrothal to Ignacio.

One evening in early December I chanced, through the purest accident, to overhear her sharp repulsion of the suit that he had evidently been pressing.

“Madonna,” I heard him answer, with a snarl, “I may yet prove to you that you have been unwise so to use Ramiro del’ Orca.”

“If you so much as venture to address me again upon the subject,” she returned in the very chilliest accents, “I will lay this matter of your odious suit before your master Cesare Borgia.”

They must have caught the sound of my footsteps in the gallery in which they stood, and Ramiro moved away, his purple face pale for once, and his eyes malevolent as Satan’s.

I reflected with pleasure that perhaps we had now seen the last of him, and that before that threat of Madonna’s he would see fit to ride home to Cesena and remain there. But I was wrong. With incredible effrontery and daring he lingered. The morrow was a Sunday, and, on the Tuesday or Wednesday following, Cesare Borgia and his cousin Ignacio were expected. Filippo was in the best of moods, and paid more heed to the Governor of Cesena’s presence at Pesaro than he did to mine. It may be that he imagined Ramiro del’ Orca to be acting under Cesare’s instructions.

That Sunday night we supped together, and we were all tolerably gay, the topic of our talk being the coming of the bridegroom. Madonna’s was the only downcast face at the board. She was pale and worn, and there were dark circles round her eyes that did much to mar the beauty of her angel face, and inspired me with a deep and sorrowing pity.

Ramiro announced his intention of leaving Pesaro on the morrow, and ere he went be begged leave to pledge the beautiful Lady of Santafior, who was so soon to become the bride of the valiant and mighty Ignacio Borgia. It was a toast that was eagerly received, so eager and uproariously that even that poor lady herself was forced to smile, for all that I saw it in her eyes that her heart was on the point of breaking.

I remember how, when we had drunk, she raised her goblet—a beautiful chaste cup of solid gold—and drank, herself, in acknowledgment; and I remember, too, how, chancing to move my head, I caught a most singular, ill-omened smile upon the coarse lips of Messer Ramiro.

At the time I thought of it no more, but in the morning when the horrible news that spread through the Palace gained my ears, that smile of Ramiro del’ Orca recurred to me at once.

It was from the seneschal of the Palace that I first heard that tragic news. I had but risen, and I was descending from my quarters, when I came upon him, his old face white as death, a palsy in his limbs.

“Have you heard the news, Ser Lazzaro?” he cried in a quavering voice.

“The news of what?” I asked, struck by the horror in his face.

“Madonna Paola is dead,” he told me, with a sob.

I stared at him in speechless consternation, and for a moment I seemed forlorn of sense and understanding.

“Dead?” I remember whispering. “What is it you say?” And I leaned forward towards him, peering into his face. “What is it you say?”

“Well may you doubt your ears,” he groaned. “But, Vergine Santissima! it is the truth. Madonna Paola, that sweet angel of God, lies cold and stiff. They found her so this morning.”

“God of Heaven!” I cried out, and leaving him abruptly I dashed down the steps.

Scarce knowing what I did, acting upon an impulsive instinct that was as irresistible as it was unreasoning, I made for the apartments of Madonna Paola. In the antechamber I found a crowd assembled, and on every face was pallid consternation written. Of my own countenance I had a glimpse in a mirror as I passed; it was ashen, and my hollow eyes were wild as a madman’s.

Someone caught me by the arm. I turned. It was the Lord Filippo, pale as the rest, his affectations all fallen from him, and the man himself revealed by the hand of an overwhelming sorrow. With him was a grave, white-bearded gentleman, whose sober robe proclaimed the physician.

“This is a black and monstrous affair, my friend,” he murmured.

“Is it true, is it really true, my lord?” I cried in such a voice that all eyes were turned upon me.

“Your grief is a welcome homage to my own,” he said. “Alas, Dio Santo! it is most hideously true. She lies there cold and white as marble, I have just seen her. Come hither, Lazzaro.” He drew me aside, away from the crowd and out of that antechamber, into a closet that had been Madonna’s oratory. With us came the physician.

“This worthy doctor tells me that he suspects she has been poisoned, Lazzaro.”

“Poisoned?” I echoed. “Body of God! but by whom? We all loved her. There was not in Pesaro a man worthy of the name but would have laid down his life in her service. Who was there, then, to poison that dear saint?”

It was then that the memory of Ramiro del’ Orca, and the look that in his eyes I had

Nowadays a big variety of genres are exist. In our electronic library you can choose any book that suits your mood, request and purpose. This website is full of free ebooks. Reading online is very popular and become mainstream. This website can provoke you to be smarter than anyone. You can read between work breaks, in public transport, in cafes over a cup of coffee and cheesecake.

Nowadays a big variety of genres are exist. In our electronic library you can choose any book that suits your mood, request and purpose. This website is full of free ebooks. Reading online is very popular and become mainstream. This website can provoke you to be smarter than anyone. You can read between work breaks, in public transport, in cafes over a cup of coffee and cheesecake.

Comments (0)