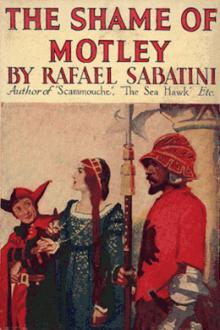

The Shame of Motley by Rafael Sabatini (the reading strategies book txt) 📖

- Author: Rafael Sabatini

- Performer: -

Book online «The Shame of Motley by Rafael Sabatini (the reading strategies book txt) 📖». Author Rafael Sabatini

Ramiro eyed him with cynical amusement.

“Your hand shakes, Mariani,” he derided him. “Are you cold? Go warm yourself,” he added, with a brutal laugh and a jerk of his thumb towards the fire.

My eyes have looked upon some gruesome sights, and I have heard such tales of ruthless cruelty as you would deem almost passing possibility. I have read of the awful doings of the Lord Bernabo Visconti at Milan in the olden time, but I believe that compared with this monster of Cesena that same Bernabo was no worse than a sucking dove. How it befell that men permitted him to live, how it was that none bethought him to put poison in his wine or a knife in his back, is something that I shall never wholly understand. Could it be that these robbers of whom he made a hedge for his protection were no better than himself, or was it that the man’s terrific brutality was on such a scale that it filled them with an almost supernatural awe of him? To men better versed than am I in the mysterious ways of human nature do I leave the answering of these questions.

The ogre turned his bloodshot eyes upon me, as with his hand he caressed his tawny beard. He seemed to have cooled a little now, and to have regained some mastery of his drunken self. Old Mariani tottered back to his buffet, and stood leaning against it, his eyes wandering, with the look of a man demented, to the fire that had devoured his child. There, indeed, if he escaped the madness with which the poignancy of his grief was threatening him, was a tool that might turn its edge against this inhuman monster, this devil, this bloody carnifex of a Governor.

“Chance,” said Ramiro, “has designed that you should see something of how we deal with clumsy knaves at Cesena, Boccadoro. To disobedient ones I can assure you that we are not half so merciful. There is no such short shrift for them. You have had more than the time I promised you for reflection. The garments await you yonder. Let us know—”

The door opened suddenly, and a servant entered.

“A courier from the Lord Vitellozzo Vitelli, Tyrant of Citt� di Castello,” he announced, unwittingly breaking in upon Ramiro’s words, “with urgent messages for the high and Mighty Governor of Cesena.”

On the instant Ramiro rose, the expression of his face changing from cynical amusement to sober concern, the task upon which he was engaged forgotten.

“Admit him instantly,” he commanded. And whilst he waited he paced the chamber in long strides, his chin thrust slightly forward, suggestive of deep thought. And during that pause, I, too, was thinking. Not indeed of him, nor vainly speculating upon such matters as might be involved in the message, the announcement of which seemed so deeply to engage his mind, but chiefly of my own and Madonna Paola’s concerns.

It was not fear of what I had seen that now sent my thoughts into a new channel and inspired me with the wisdom of obeying Ramiro del’ Orca’s behest that I should don the hateful motley and play the Fool for his diversion. It was not that I feared death; it was that I feared what the consequences of my death might be to Paola di Santafior.

However desperate a position may seem, unlooked-for loopholes often present themselves, and so long as we live and have sound limbs to aid us to seize such opportunities as may offer, it is a weak thing utterly to abandon hope.

Was it, then, not better to submit to the shame of the motley once again for a little time, when by so doing I might perhaps live to work my own salvation, and Madonna’s should she suffer capture, rather than stubbornly to invite him to put me to death out of a feeling of false pride?

The very resolve seemed to lend me strength and to revive the hope that lay moribund in my breast. And then, scarce was it taken, when the door again opened, and a man, who was splashed from head to foot with mud, in earnest of how hard he had ridden, was ushered in.

He advanced to Meser Ramiro, bowed and presented a package. Ramiro broke the seal, and standing with his back to the fire, immediately in the light shed by one of the wax torches, he read the letter. Then his eyes wandered to the man who had brought it, and to me it seemed that they dwelt particularly upon the hat the courier was holding in his hand.

“Take this good fellow to the kitchen,” he bade the servant that had introduced him, “let him be fed and rested.” Then, turning to the man, himself, “I shall require you to set out at daybreak with my answer,” he said; and so, with a wave of the hand, he dismissed him. As the messenger departed Ramiro returned to the table, filled himself a cup of wine and drank.

“What says the Lord Vitelli?” Lampugnani ventured to ask him.

“If he knew you,” answered Ramiro, with a scowl, “he would counsel me to strangle some of the over-inquisitive rascals that surround me.”

“Over-inquisitive?” echoed Lampugnani boldly. “Body of God! It were enough to wake the curiosity of an ecstatic hermit to have a mud-splashed courier from Citta di Castello at Cesena three times within one little week.”

Ramiro looked at him, and by his glance it was plain to see that the words had jarred his temper. Whatever it was that Vitelli wrote to Ramiro, this gentleman was not minded to divulge it.

“If you have supped, Lampugnani,” said the Governor slowly, his eyes upon his offending officer, “perhaps you will find some duty to perform ere you seek your bed.”

Lampugnani turned crimson, and for a moment seemed to hesitate. Then he rose. He was a man of choleric aspect, and that he served under Ramiro del’ Orca was as much a danger to the Governor as to himself. He had not the air of one whom it was wise to threaten in however veiled a manner.

“Shall I fetch you this fellow’s hat ere I sleep?” he inquired, with contemptuous insolence.

Not a word did Ramiro answer him, but his glance fastened upon Lampugnani with an expression before which that impudent ruffian lowered his own bold eyes. Thus for a moment; then with an awkward laugh to cover the intimidation that he felt, Lampugnani walked heavily from the room and banged the door after him.

There was about it all a strangeness that set my wits to work in a mighty busy fashion. That work suffered interruption by the harsh voice of Ramiro.

“Are you resolved, Boccadoro?” he growled at me. “Have you decided for the motley or the cord?”

Instantly I fell into the part I was to play.

“Did I choose the latter,” said I, with an assumption of sudden airiness and such a grimace as was part and parcel of my old-time trade, “then were I truly worthy of the former, for I should have proved myself, indeed, a fool. Yet if I choose the former, I pray that you’ll not follow the same course of reasoning, and hold me worthy of the latter.”

When he had understood its subtleties; for his wits were of a quality that would have disgraced a calf, he roared at the conceit, and seemingly thrown into a better humour by the promise of more such entertainment, he bade my guards release me, and urged me to assume the motley without more delay.

What time I was obeying him my mind was returning to that matter of Lampugnani’s words, and it is not difficult to understand how I should arrive at the only possible conclusion they suggested. The hats of the other messengers from Vitelli, that the officer had mentioned, had been brought to Ramiro. The reason for this that at once arose in my mind was that within the messenger’s hat there was a second and more secret communication for the Governor.

This secrecy and Ramiro’s display of anger at seeing a hint of it betrayed by Lampugnani struck me, not unnaturally, as suspicious. What were these hidden communications that passed between Vitellozzo Vitelli and the Governor of Cesena? It was a matter of which I could not pretend to offer a solution, but, nevertheless, it was one, I thought, that promised to repay investigation.

Ramiro grew impatient, and my reflections suffered interruption by his rough command that I should hasten. One of the men-at-arms helped me to truss my points, and when that was done I stepped forward—Boccadoro the Fool once more.

For an hour or so that night I played the Fool for Messer Ramiro’s entertainment in a manner which did high justice to the fame that at Pesaro I had earned for the name of Boccadoro.

Beginning with quip and jest and paradox, aimed now at him, now at the officer who had remained to keep him company in his cups, now at the servants who ministered to him, now at the guards standing at attention, I passed on later to play the part of narrator, and I delighted his foul and prurient mind with the story of Andreuccio da Perugia and another of the more licentious tales of Messer Giovanni Boccacci. I crimson now with shame at the manner in which I set myself to pander to his mood that with my wit I might defend my life and limbs, and preserve them for the service of my Holy Flower of the Quince in the hour of her need.

One man alone of all those present did I spare my banter. This was the old seneschal, Miriani. He stood at his post by the buffet, and ever and anon he would come forward to replenish Messer Ramiro’s cup in obedience to the monsters imperious orders.

What fortitude was it, I wondered, that kept the old man outwardly so calm? His face was as the face of one who is dead, its features set and rigid, its colour ashen. But his step was tolerably firm, and his hand seemed to have lost the trembling that had assailed it under the first shock of the horror he had witnessed.

As I watched him furtively I thought that were I Ramiro I should beware of him. That frozen calm argued to me some terrible labour of the mind beneath that livid mask. But the Governor of Cesena appeared insensible, or else he was contemptuous of danger from that quarter. It may even have delighted his outrageous nature to behold a man whose son he had done to death with such brutality continue obedient and submissive to his will, for it may have flattered his vanity by the concession that bearing seemed to make to his grim power.

An hour went by, my second tale was done, and I was now entrancing Messer Ramiro with some impromptu verses upon the divorce of Giovanni Sforza, a theme set me by himself, when I was interrupted by the arrival of a soldier, who entered unannounced.

I paled and turned cold at the cry with which Ramiro rose to greet him, and the words he dropped, which told me that here was one of the riders of the party that, under Lucagnolo, had been ordered to search the country about Cattolica. Had they found Madonna?

“Messer Lucagnolo,” the fellow announced, has sent me to report to you the failure of his search to the west and north of Cattolica. He has beaten the country

Nowadays a big variety of genres are exist. In our electronic library you can choose any book that suits your mood, request and purpose. This website is full of free ebooks. Reading online is very popular and become mainstream. This website can provoke you to be smarter than anyone. You can read between work breaks, in public transport, in cafes over a cup of coffee and cheesecake.

Nowadays a big variety of genres are exist. In our electronic library you can choose any book that suits your mood, request and purpose. This website is full of free ebooks. Reading online is very popular and become mainstream. This website can provoke you to be smarter than anyone. You can read between work breaks, in public transport, in cafes over a cup of coffee and cheesecake.

Comments (0)