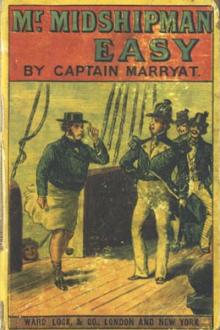

Mr. Midshipman Easy by Frederick Marryat (reading tree .TXT) 📖

- Author: Frederick Marryat

- Performer: -

Book online «Mr. Midshipman Easy by Frederick Marryat (reading tree .TXT) 📖». Author Frederick Marryat

After a long conversation Jack was graciously dismissed, Captain Wilson being satisfied from what he had heard that Jack would turn out a very good officer, and had already forgotten all about equality and the rights of man; but there Captain Wilson was mistaken tares sown in infancy are not so soon rooted out.

Jack went on deck as soon as the captain had dismissed him, and found the captain and officers of the Spanish corvette standing aft, looking very seriously at the Nostra Signora del Carmen. When they saw our hero, whom Captain Wilson had told them was the young officer who had barred their entrance into Carthagena, they turned their eyes upon him, not quite so graciously as they might have done.

Jack, with his usual politeness, took off his hat to the Spanish captain, and, glad to have an opportunity of sporting his Spanish, expressed the usual wish, that he might live a thousand years. The Spanish captain, who had reason to wish that Jack had gone to the devil at least twenty-four hours before, was equally complimentary, and then begged to be informed what the colours were that Jack had hoisted during the action. Jack replied that they were colours to which every Spanish gentleman considered it no disgrace to surrender, although always ready to engage, and frequently attempting to board. Upon which the Spanish captain was very much puzzled. Captain Wilson, who understood a little Spanish, then interrupted by observing-

“By-the-bye, Mr Easy, what colours did you hoist up? We could not make them out. I see Mr Jolliffe still keeps them up at the peak.”

“Yes, sir,” replied Jack, rather puzzled what to call them, but at last he replied, “that it was the banner of equality and the rights of man.”

Captain Wilson frowned, and Jack, perceiving that he was displeased, then told him the whole story, whereupon Captain Wilson laughed, and Jack then also explained, in Spanish, to the officers of the corvette, who replied, “that it was not the first time, and would not be the last, that men had got into a scrape through a petticoat.”

The Spanish captain complimented Jack on his Spanish, which was really very good (for in two months, with nothing else in the world to do, he had made great progress), and asked him where he had learnt it.

Jack replied, “At the Zaffarine Islands.”

“Zaffarine Isles,” replied the Spanish captain; “they are not inhabited.”

“Plenty of ground-sharks,” replied Jack.

The Spanish captain thought our hero a very strange fellow, to fight under a green silk petticoat, and to take lessons in Spanish from the ground-sharks. However, being quite as polite as Jack, he did not contradict him, but took a huge pinch of snuff, wishing from the bottom of his heart that the ground-sharks had taken Jack before he had hoisted that confounded green petticoat.

However, Jack was in high favour with the captain, and all the ship’s company, with the exception of his four enemies -the master, Vigors, the boatswain, and the purser’s steward. As for Mr Vigors, he had come to his senses again, and had put his colt in his chest until Jack should take another cruise. Little Cossett, at any insulting remark made by Vigors, pointed to the window of the berth and grinned; and the very recollection made Vigors turn pale, and awed him into silence.

In two days they arrived at Gibraltar-Mr Sawbridge rejoined the ship-so did Mr Jolliffe-they remained there a fortnight, during which Jack was permitted to be continually on shore-Mr Asper accompanied him, and Jack drew a heavy bill to prove to his father that he was still alive. Mr Sawbridge made our hero relate to him all his adventures, and was so pleased with the conduct of Mesty that he appointed him to a situation which was particularly suited to him,-that of ship’s corporal. Mr Sawbridge knew that it was an office of trust, and provided that he could find a man fit for it, he was very indifferent about his colour. Mesty walked and strutted about at least three inches taller than he was before. He was always clean, did his duty conscientiously, and seldom used his cane.

“I think, Mr Easy,” said the first lieutenant, “that as you are so particularly fond of taking a cruise,”-for Jack had told the whole truth,-“it might be as well that you improve your navigation.”

“I do think myself, sir,” replied Jack, with great modesty, “that I am not yet quite perfect.”

“Well, then, Mr Jolliffe will teach you; he is the most competent in this ship: the sooner you ask him the better, and if you learn it as fast as you have Spanish, it will not give you much trouble.’

Jack thought the advice good; the next day he was very busy with his friend Jolliffe, and made the important discovery that two parallel lines continued to infinity would never meet.

It must not be supposed that Captain Wilson and Mr Sawbridge received their promotion instanter. Promotion is always attended with delay, as there is a certain routine in the service which must not be departed from. Captain Wilson had orders to return to Malta after his cruise. He therefore carried his own despatches away from England-from Malta the despatches had to be forwarded to Toulon to the Admiral, and then the Admiral had to send to England to the Admiralty, whose reply had to come out again. All this, with the delays arising from vessels not sailing immediately, occupied an interval of between five and six months-during which time there was no alteration in the officers and crew of his Majesty’s sloop Harpy.

There had, however, been one alteration; the gunner, Mr Linus, who had charge of the first cutter in the night action in which our hero was separated from his ship, carelessly loading his musket, had found himself minus his right hand, which, upon the musket going off as he rammed down, had gone off too. He was invalided and sent home during Jack’s absence, and another had been appointed, whose name was Tallboys. Mr Tallboys was a stout dumpy man, with red face, and still redder hands; he had red hair and red whiskers, and he had read a great deal-for Mr Tallboys considered that the gunner was the most important personage in the ship. He had once been a captain’s clerk, and having distinguished himself very much in cutting-out service, had applied for and received his warrant as a gunner. He had studied the ‘Art of Gunnery,” a part of which he understood, but the remainder was above his comprehension: he continued, however, to read it as before, thinking that by constant reading he should understand it at last. He had gone through the work from the title-page to the finis at least forty times, and had just commenced it over again. He never came on deck without the gunner’s vade mecum in his pocket, with his hand always upon it to refer to it in a moment.

But Mr Tallboys had, as we observed before, a great idea of the importance of a gunner, and, among other qualifications, he considered it absolutely necessary that he should be a navigator. He had at least ten instances to bring forward of bloody actions, in which the captain and all the commissioned officers had been killed or wounded and the command of the ship had devolved upon the gunner.

“Now, sir,” would he say, ‘if the gunner is no navigator, he is not fit to take charge of his Majesty’s ships. The boatswain and carpenter are merely practical men; but the gunner, sir, is, or ought to be, scientific. Gunnery, sir, is a science-we have our own disparts and our lines of sight-our windage, and our parabolas, and projectile forces-and our point blank, and our reduction of powder upon a graduated scale. Now, sir, there’s no excuse for a gunner not being a navigator; for knowing his duty as a gunner, he has the same mathematical tools to work with.” Upon this principle, Mr Tallboys had added John Hamilton Moore to his library, and had advanced about as far into navigation as he had in gunnery, that is, to the threshold, where he stuck fast, with all his mathematical tools, which he did not know how to use. To do him justice, he studied for two or three hours every day, and it was not his fault if he did not advance-but his head was confused with technical terms; he mixed all up together, and disparts, sines and cosines, parabolas, tangents, windage, seconds, lines of sight, logarithms, projectiles, and traverse sailing, quadrature, and Gunter’s scales, were all crowded together, in a brain which had not capacity to receive the rule of three. “Too much learning,” said Festus to the apostle, “hath made thee mad. Mr Tallboys had not wit enough to go mad, but his learning lay like lead upon his brain: the more he read, the less he understood, at the same time that he became more satisfied with his supposed acquirements, and could not speak but in “mathematical parables.” “I understand, Mr Easy,” said the gunner to him one day, after they had sailed for Malta, “that you have entered into the science of navigation-at your age it was high time.”

“Yes,” replied Jack, “I can raise a perpendicular, at all events, and box the compass.”

“Yes, but you have not yet arrived at the dispart of the compass.”

“Not come to that yet,” replied Jack.

“Are you aware that a ship sailing describes a parabola round the globe?”

“Not come to that yet,” replied Jack.

“And that any propelled body striking against another flies off at a tangent?”

“Very likely,” replied Jack; “that is a ‘sine’ that he don’t like it.”

“You have not yet entered into ‘acute’ trigonometry?”

“Not come to that yet,” replied Jack.

“That will require very sharp attention.’

“I should think so,” replied Jack.

“You will then find out how your parallels of longitude and latitude meet.”

“Two parallel lines, if continued to infinity will never meet,” replied Jack.

“I beg your pardon,” said the gunner.

“I beg yours,” said Jack.

Whereupon Mr Tallboys brought up a small map of the world, and showed Jack that all the parallels of latitude met at a point at the top and the bottom.

“Parallel lines never meet,” replied Jack, producing Hamilton Moore.

Whereupon Jack and the gunner argued the point, until it was agreed to refer the case to Mr Jolliffe, who asserted, with a smile, “That those lines were parallels, and not parallels.”

As both were right, both were satisfied.

It was fortunate that Jack would argue in this instance: had he believed all the confused assertions of the gunner, he would have been as puzzled as the gunner himself. They never met without an argument and a reference, and as Jack was put right in the end, he only learnt the faster. By the time that he did know something about navigation, he discovered that his antagonist knew nothing. Before they arrived at Malta, Jack could fudge a day’s work.

But at Malta Jack got into another scrape. Although Mr Smallsole could not injure him, he was still Jack’s enemy; the more so as Jack had become very popular: Vigors also submitted, planning revenge; but the parties in this instance were the boatswain and purser’s steward. Jack still continued his forecastle conversations with Mesty: and the boatswain and purser’s steward, probably from their respective ill-will towards our hero, had become great allies. Mr Easthupp now put on his best Jacket to walk

Comments (0)