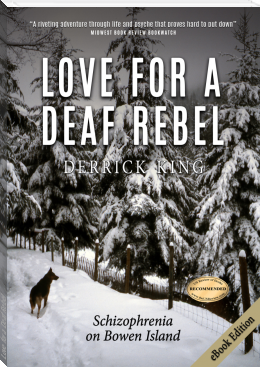

Love for a Deaf Rebel by Derrick King (romantic books to read txt) 📖

- Author: Derrick King

- Performer: -

Book online «Love for a Deaf Rebel by Derrick King (romantic books to read txt) 📖». Author Derrick King

“Water dripped on my back.” I turned on the utility light and stood on the bed. “Water is dripping from the skylight.”

I covered the blanket with plastic and let Whisky in. We slid under the blanket and the plastic sheet. Whisky lay down on the floor next to Pearl.

“Why does Whisky goes to your side?”

“Animals prefer deafies. I told you before. Is it quiet here?”

“Inside, I hear the firewood burning and the refrigerator motor. Outside, the wind moves the leaves, like this.” I rubbed her hands. “The leaves whisper.”

On our first night on Bowen Island, we made love while I listened to water dripping on the plastic sheet above my back, ticking like a time bomb.

At sunrise, Whisky’s barking jolted us awake. We looked out and saw two deer on the hill.

“One window is higher than the other,” signed Pearl.

“You are right. It looks strange. I will ask Frank to fix it.”

We dressed, made the bed, and covered it with plastic.

After breakfast, Whisky barked furiously. Frank and his family had arrived. Mrs. Schutt gave us a carrot cake as a housewarming gift. Frank showed her around the house. Then he and his son resumed sanding drywall while Pearl and I continued tidying up the property. Whisky, tied to a tree, barked and lunged at Frank whenever he came near.

That evening, when we returned from dinner at the Snuggler, fine white gypsum powder covered everything as if a blizzard had blown through the house. The dust was so fine it clogged the vacuum cleaner in minutes. We could only sweep with Dustbane and wet-mop. The dust filled our nostrils and made us as dirty as the house.

We showered in the night air by standing naked on a plank behind the house and taking turns aiming the hose. The water system had not yet been installed, so the hose blasted cold groundwater at firehose pressure. Then, wearing only sandals, we ran to the basement by flashlight to warm ourselves before the woodstove, like a sauna in reverse.

On Monday morning, we dressed in the basement, standing on a piece of plywood on the gravel floor. We drove to the cove, parked, and walked onto the ferry for our first commute, along with 200 neighbors. I shaved in the ferry washroom and was surprised to find other men shaving.

We commuted by ferry and bus together, ate dinner in the Snuggler together, and, during the week, showered downtown at the YMCA. Because vehicle fare was expensive, we drove the truck onto the ferry only once a week to buy supplies. We were becoming alarmed that progress had slowed when so much work was unfinished, especially Pearl.

“When are we going to have a toilet, lights, and a bath? My holiday starts next week. I have to paint.”

“Frank said he would finish sanding next Sunday. He’s waiting for the electrical inspector. Then an electrician will connect the house, and we will have power and water.”

I used a vacation day to meet the electrical inspector. Frank wasn’t licensed, so I had to attest that I, the homeowner, had done the wiring. I must have made a good impression on the inspector because he approved Frank’s wiring without entering the house. The next day, an electrician moved the power line to the house, so when we came home from work, we had electricity in the sockets and a few lights for the first time. The light fell on chaos, but we were thrilled that civilization had reached us.

On the weekend, Frank plumbed the wellhead to the house and switched on the water. Pearl flushed the toilet and cheered. After two weeks of camping, we had hot water and a toilet.

While Frank and his son sanded drywall, I filled in the pipe trench, which ran from the wellhead to the house. I discovered Frank had spliced two pieces of pipe for our water main, and his splice was leaking. When I examined it, Frank shouted at me to keep shoveling—to bury his defect under two feet of soil! I re-spliced the pipe and made sure the leak had stopped before I buried it.

When Frank left, we put on masks and swept and wet-mopped the new piles of dust. At bedtime, I reached under the mattress, took the pistol, unloaded it, and handed it to Pearl.

“For self-defense. Do you remember how a rifle works?”

Pearl nodded and mimed pulling the bolt and taking a shot.

“A pistol is the same. It fires when it is loaded, the bolt is pulled, and the safety is off.” I loaded the gun, cocked it, and turned the safety lever on. “Now it’s safe—try it.”

Pearl pulled the trigger. Nothing happened.

I turned the safety off. “Now, it’s not safe. The red dot means it will fire.” I turned the safety back on. “We will leave the safety on. Whisky is your alarm; the gun is your defense. If a stranger comes, lock the front door, come here in the bedroom, and close the door. Turn the safety off, stand in the corner, and wait. If a man walks into the bedroom, shoot him. Then call the police.”

“Will I go to jail?”

“No. When he’s inside, not invited, and you fear assault, you may shoot him. Leo keeps a pistol under the mattress for his wife, too.”

Pearl hugged me. “You protect me. I love you.”

The power failed. I took the flashlight from my pocket and used it to find the kerosene lamp in the kitchen and light it. The W-shaped flame cast an island of yellow light. It flickered as I carried it to the bedroom.

“I feel lost when the power goes off, like I am deaf-blind.”

Pearl stayed home and painted while I commuted to work.

When I came home, Pearl signed, “When I was painting, the ladder shook, so I looked down. Whisky was bumping it to call me. The kitten was in his mouth, dead. Whisky looked sad. His eyes said, ‘Please fix my friend.’ We were both sad. Tonight, your first job is to bury the cat.”

The telephone rang. As I put down the telephone, I laughed. “A man saw our advertisement and asked if he could rent our barn to live in—himself, with no toilet, heat, and light!”

“There are some weird people on Bowen Island.”

We decided to introduce ourselves to Fran Thaxter so that she would have no reason to surprise us with a visit. On a Saturday morning, we walked across the street to a graveled compound with a bungalow and pickup truck on one side and cinder-block sheds of machinery, construction materials, and fuel drums on the other. Smoke wafted from the chimney.

When I rang the doorbell, barking erupted inside. A woman about ten years older than us with blonde hair, jeans, and an intense face opened the door and held back a German Shepherd.

“I was wondering when you’d drop by. Come in! On Bowen, you can drop in on your neighbors and borrow a cup of sugar. Don’t mind Bear.”

The house smelled of wood smoke and cigarettes. A burly man dressed like a lumberjack shook my hand. “Morning. I’m Wayne.”

We accepted coffee but declined the cigarettes. Fran handed us mugs of Nescafé and we sat down. A wooden model of our house sat on top of their TV.

“I hope you’re not upset we bought your house,” I signed and said.

“No, that land wasn’t important. We own the land all around the lake, hundreds of acres. We’ll subdivide it when prices recover.” Fran pointed to the model. “My former husband and I had it designed for adults at one end and teenagers at the other so the kids wouldn’t hear us in our bedroom. That’s why the living and family rooms are in the middle. We planned how the sun and moon would shine through the windows and skylights. Take the model with you.”

“Keep it. We have the blueprints.”

“My husband wanted to eat in the dining room every day. That’s why the dining room has the best view. I’d love to see the house when you are finished.”

We didn’t want to owe Fran any favors, so we kept our visit brief.

I searched the property titles at the Land Titles Office. The land around the lake was owned by the Union Steamship Company, which had once owned much of Bowen Island. Fran’s lying only served to impress others or, perhaps, herself.

Trout Lake Farm

Our lives settled into a routine. We awoke at 6:30, we took the 7:30 ferry followed by the express bus, and we arrived downtown at 8:30. We enjoyed our commute, for we signed for ten hours a week, talking about everything. We shared the newspaper, and we read books. The ferry and bus were havens for bookworms, and we often talked to other commuters. Sometimes, post office shift changes forced us to travel separately and take turns picking each other up in the truck or take turns hitchhiking on the trunk road.

One afternoon, I sat on the express bus next to a man in a black cotton overcoat. Although his hair was thinning and tinged with gray, he appeared just a few years older than me. His aviator glasses magnified the twinkle in his eye. He looked up from reading Object Oriented Programming.

“Haven’t you anything more interesting to read than Guide to Being Your Own Contractor?” He laughed.

I couldn’t help but laugh, too. “I see you are in computers.”

“That’s my job. The commute gives me time to learn and think. In a month, you can sit on the top of the ferry and suntan while you commute. Take that, citysiders!”

“How long have you been living on Bowen Island?”

“Fifteen years.”

I smiled. “That’s a long time.”

“On Bowen, either you just got here, or you’ve been here forever. You love it, or you hate it. I came in the counterculture days—back-to-the-land, Jefferson Airplane, the sixties, all of it.”

“Where do you live?”

“In a house where I can walk to the ferry. But I used to live on a farm. I raised sheep for a decade.”

“Did it pay?”

“It’s a long story.”

“It’s a long commute.”

The man looked at his watch and smiled. “Then I’d love to share it with you. Once upon a time, there was a guy named Fernie, an engineer and investor who never lived on the island. Fernie bought twenty acres nestled in the hills back when land was cheap. It had a broken-down cabin built by the original settlers. It was lovely, but to Fernie, it was a tax deduction—provided it was worked as a farm. So I took care of Fernie’s place for free rent, a stipend, and a share. I became a sharecropper. There were only 500 people on Bowen Island in 1972.”

“How long had the cabin been abandoned?”

“Not long. A few years before me, a hippie couple approached Fernie and asked if they could squat in it if they fixed it up. Fernie agreed. By the third winter, they’d had enough. They told me about the place. I moved in, and I built the farm for Fernie.”

“Alone?”

“Most of the time. It was fabulous, as in living a fable. The stars were my friends. Living without human reinforcement purified my soul.”

“Why did you give it up?”

“I quit while I was ahead,” he said, with an enigmatic smile. “I moved to the cove and started a garage and machine shop.”

“What did you do for power and water?”

“I had no power, just a battery for the stereo that Fernie charged for me. Kerosene lighting, wood heating, water from a well.”

“What was the cabin like?”

“It had one room and a loft for storage. I hung my toilet seat on the wall behind the stove and carried it to the outhouse when I needed it. Nothing moves bowels better than a hot seat in cold air.”

“What a unique living room decoration that must have been.”

Our bus arrived, and we waited in the ferry departure lounge. He took a bottle of Karo out of his overcoat and took a swig. His breath smelled of ammonia.

“I was starting to fade. Want some?”

“Corn syrup? No, thanks. Diabetes?”

“Type One.”

“Is that why you quit?”

“No. I went blind.”

“I saw you reading!”

The man grinned. “I was driving, and then the world started to go dark—retinal hemorrhage. I stopped and waved for someone to take me to a hospital. I was blind for years, a member of the Canadian National Institute for the Blind. I learned to read Braille, walk with a white cane, and eat by putting my meat on the plate at six o’clock. I never mastered urinals, though. The CNIB gave me vocational training,

Comments (0)