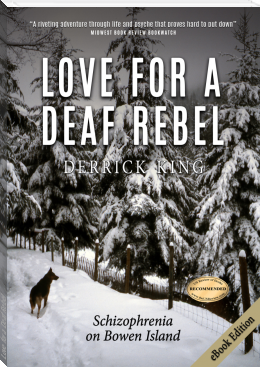

Love for a Deaf Rebel by Derrick King (romantic books to read txt) 📖

- Author: Derrick King

- Performer: -

Book online «Love for a Deaf Rebel by Derrick King (romantic books to read txt) 📖». Author Derrick King

“Where do you sleep?” signed Pearl.

“On cots. We put them near the stove at night.”

We took off our coats and slid onto benches on either side of the kitchen table. All of us wore quilted lumberjack shirts. Our bedroom was a resort compared to these Boy Scout conditions.

Stanley opened the wine, and I proposed a toast.

Pearl squeezed close to me. “I’m freezing.”

I put my hand on the window. “The glass is freezing! Where did you buy single-glazed windows?”

“I made them!” Stanley said proudly. “They’re cheaper than commercial windows.”

“Stanley, your heat is flying out the window! You’ll spend all summer cutting firewood. And single-glazed windows aren’t up to code, so you can’t get a Certificate of Occupancy, and you can’t connect electricity.”

After eating beef-and-potato stew, Pearl helped Gertrude wash the dishes. Stanley walked through the plastic sheets, and I followed him. We stood at the top of the stairs, under the stars, and urinated onto the ground.

“Derrick, to understand what you see, you need to know I’m bankrupt. When the garnishee order arrived, Eaton’s sacked me; Mrs. Rottweiler was their excuse. Now I, a debt collector, have no means to settle my debts, let alone finish our house.”

Pearl saw that although Frank had done a bad job and delayed us by a year, it was possible to do worse and for a wife to suffer more hardship with no end in sight. Frank had spoiled our house to make more money, while Stanley had spoiled his house because he had no money. Our best man and maid of honor were building an illegal, oversized shack.

We awoke to a white-and-green winter wonderland; a foot of snow had fallen during the night. The view in every direction, from every window, was majestic. Pearl looked at our frozen clothes on the clothesline and laughed; they looked like ghosts.

I walked to the barn to do the chores, savoring the morning air as the snow crystals sparkled. But the drinking water had frozen, splitting the pails, so the horses were thirsty. No water came from the barn tap, now frozen. I fed the animals and walked back to the house.

“The barn has no water. The barn pipes need electric heat, a new project. Now, we have to carry water until the ice thaws—two pails, fifteen kilograms each, twice a day. It’s good we have hay and grain in the barn and firewood in the basement because the truck can’t drive up the road now.”

“My uncle used to put ‘mol—’ in the water to keep it from freezing.”

“Molasses. I read about that. Let’s try it.”

Molasses didn’t work; the water still froze quickly. Each day, we watched the barn thermometer go lower, down to -15 Celsius. For weeks, we carried our groceries up the driveway in backpacks. We walked flashlight-in-hand, or when our hands were full, flashlight-in-teeth, for winter commuting was always dark. Sometimes, we slipped and slid down the driveway and slogged up again with snow in our boots.

Whisky loved the snow. When we threw sticks, he would chase the stick as fast as he could, then spin and slide while struggling to stop. We felt grateful to live so close to nature.

A week later, the pipes in the house froze.

“Ross was right! The pipes froze because Frank put them in the attic. We must warm them, or they will burst and water will ruin the house. And no water means no fire insurance.”

Pearl was livid. “Frank is preventing me from living like a woman!”

All we could do was heat the house to tropical temperatures, so hot that we could walk through it nude in the middle of winter, and our lips cracked from the desiccated air. After days of burning firewood at a stupendous rate, water returned to our taps.

The Undercurrent reported it was the coldest winter in a decade.

“Hello,” I said to two newborn lambs. An ewe looked up from the straw, her fleece thick with lanolin, the greasy smell hanging in the air. I ran to the house, told Pearl, and called Alan.

The driveway was impassible, so Alan and Rose parked by the road and trekked up the hill. Rose cleared the ewe’s teats by milking with two fingers while Alan disinfected the lambs’ navels with iodine. He took a tool from his pocket, put a rubber ring on it, and squeezed the handle to stretch it open. “This is an Elastrator, for docking and castration. It is painless.” He pulled each lamb’s tail through the tool and pressed a lever, so the rubber ring snapped tight. “The tail will fall off in two weeks. I’ll leave this with you to castrate your kids.”

Unlike sheep, which lamb at night, Mothergoat kidded on a spring afternoon, bellowing. She delivered one kid, a buck. Daughtergoat soon gave birth to two more bucks.

The barn and its paddock were like a petting zoo, with eight lambs, four ewes, three goats, three kids, two horses, two cats, a kitten, and a dog. We were a family, and we loved it, not least because it took our minds off the house. Alan or Rose, often with their children, visited the lambs frequently even though we had taken over all their daily feedings in return for vacation relief. It was an ideal arrangement.

Virgil drove to Bowen Island for what would be his only visit. At Trout Lake, he gazed at the vista and drew a deep breath. “You got a lake, and I got a river. You son of a bitch, man, this is great! Did you see that trout breach?”

We collected handfuls of fiddleheads, the greens of spring, from around the lake and walked back up the hill. Pearl threw a stick from the woodpile over Whisky’s head. He caught it and dropped it at her feet.

“This is a rich couple’s house,” said Virgil. “The windows face the sun, and the skylights face the stars. Perfect peace.”

Pearl pointed to the unfinished west wing. “But wait until you see inside. We have peace, but I get lonely.”

“But you work, don’t you?” said Virgil.

“Yes, but I have few friends at the post office. They only gossip.”

“When people don’t have much to talk about, they gossip,” I signed and said. “Not only deaf.”

Virgil took his vial from his pocket and passed it around. “A guy on a BMW was on the ferry, a bike like yours but with a green tank. Get to know him, Derrick—he’s your neighborhood dealer.”

“How do you know?”

“His bike! The bugs were like a yellow-and-black paint job. I asked if he was coming back from Mexico. He said from California—but his bike was too dirty for that, the way a bike gets when you are too busy to stop. I know he was lying.”

“Great analysis. Would you like a tour?”

We sat three abreast in Virgil’s F250 pickup. He popped a cassette of Cuban music into the stereo, and I gave directions. After touring the island, we returned to the house.

“Help us with chores. We need to castrate and disbud the kids. You can help by holding them.”

Virgil took a joint from his pocket and lit it. “I like to smoke a joint before I castrate.” We passed the joint around.

I lit a propane torch and propped a piece of copper pipe over the flame. While the pipe warmed, Pearl and Virgil cradled each kid while I pulled its scrotum through the open rubber ring of the Elastrator and pushed the lever to close it. The kids felt nothing, but after a few minutes, they hopped silently in circles, in some discomfort but not in pain.

While Pearl and Virgil held a kid, I pressed the red-hot pipe onto one of its horn buds. Smoke curled up as the kid cried out, the bud charred, and the stench of burned hair filled the barn.

“I’ll go and cook dinner,” signed Pearl, leaving the barn.

Virgil and I cauterized the other bud. The kid ran to its mother and suckled, now silent. We disbudded the other kids.

In the house, I opened some beer, and Pearl served pasta with goat cheese.

“You steamed the fiddleheads perfectly, just like asparagus,” said Virgil. “Pearl, how do you like living in an unfinished house while your animals live in a finished barn?”

“I like it here. Many oral deafies prefer city life, but many signing deafies prefer a country life because city life has too many problems.”

“Like what?”

“I went into an elevator. It moved and stopped but didn’t open. I pounded on the door. Then someone tapped my shoulder! That elevator had doors at the back, too, but I didn’t hear the door open behind me. Sometimes, stores give you a number and call that number over the speaker. The deafie-hearie difference is smaller in the country.”

We enjoyed an evening of conversation, marijuana, cocaine, and laughter. Virgil left on the last ferry.

The days grew longer. As the kids were weaned, our milk and cheese production peaked. Pearl sold goat cheese to her colleagues. I sold it to a delicatessen. It was illegal to sell it, but we didn’t care.

We spread pasture seed with a Cyclone spreader. I installed electric heat tapes and automatic watering bowls for the barn, ending the need to carry water in winter.

The farrier came to shoe Mouse and Senator. Pearl and I watched him remove the worn horseshoes and heat new ones on a forge. When the new shoes glowed red hot, he pounded them to size on his anvil, reheated them, and nailed them to the hooves. I complimented the farrier on his medieval performance.

“I wouldn’t do anything else,” said the farrier. “Coming here doesn’t pay, though.”

“Where do you earn money?”

“At the racetrack. The owner of a $100,000 horse doesn’t care what horseshoes cost.” He handed the old horseshoes to Pearl. “For good luck. Hang them pointing up because if they turn down, your luck will spill out.”

“Tom and his family are coming,” I signed as I hung up the telephone. “They’ll stay a week while they visit Expo ‘86.”

“You didn’t tell me about Tom.”

“He is a BMW-riding friend from Saskatchewan. They are coming on two motorcycles: Tom, with his fifteen-year-old son, and his wife, with their fourteen-year-old daughter. They can take the water taxi to Expo. That will be fun for them.”

“You take them to Expo. I will go with Jodi so you won’t have to interpret.” I was disappointed Pearl didn’t want to join us.

Our visitors visited Expo nearly every day, once with me and the rest on their own. They loved Bowen Island. The children were fascinated by signing, especially by how Whisky obeyed sign language commands. They enjoyed writing to Pearl, and they loved the barn.

Tom said, “What could be finer than living in a forest by a lake, working in an office, and commuting on the sea? I walked to the lake, and I saw a naked woman dive into the water! What a place you have. Don’t ever give it up.”

“It is our dream home, except for the construction problems,” signed Pearl. “It is safe and peaceful.”

“Peaceful? Surely, noise never bothers a deaf person.”

“That’s true, but I will tell you a story. A deafie was cleaning her house. When she got to the attic, she cleaned an old lamp. A spirit popped out and signed, ‘You have three wishes. What do you want?’ The deafie signed, ‘Clean the house.’ The spirit blinked, and the house was clean. ‘You have two wishes left.’ ‘Give me hearing,’ signed the deafie. The spirit blinked, and the woman could hear. ‘You have one wish left.’ ‘Wait,’ she said, amazed to hear her voice. She shouted, ‘I can hear!’ She heard her kids fighting and yelling. She called to them, but they ignored her. She heard the TV blasting and her hearie husband’s friends shouting and swearing as they watched football. She walked to the store and heard traffic, music from the ceiling, people, machines, everything! She went home and saw the house was a mess again. ‘I wish for a peaceful house,’ she said. The spirit reappeared, and she was deaf again. ‘Thank you,’ she signed. Sometimes it is better to be deaf.”

Tom smiled. “By the way, did you know your kids are ready to eat? They can grow larger, but the feed will cost more than the meat is worth.”

“Shall we slaughter them together?”

“I’d love to! My friend and I do a hog every year. We collect scraps from the Co-op and feed our hog for nothing.”

The next day, while Pearl and Jodi went to Expo and Tom’s family went swimming in Bowen Bay, Tom and I slaughtered the kids.

Comments (0)