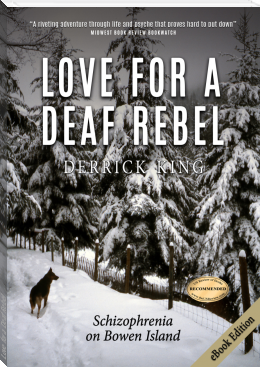

Love for a Deaf Rebel by Derrick King (romantic books to read txt) 📖

- Author: Derrick King

- Performer: -

Book online «Love for a Deaf Rebel by Derrick King (romantic books to read txt) 📖». Author Derrick King

“That’s not funny!” Pearl spat out seawater with a grin.

“Bring her up higher. Inflate her suit a bit more,” the instructor said to me.

I took her inflator hose, pressed the valve open, and blew a lungful of air into her suit.

Pearl screamed. “My tit!”

I had forgotten to start blowing air before I opened the valve, so I had blown a spoonful of cold seawater into her drysuit along with the air. We shared contagious laughter at the farce. Pearl was a good sport.

I looked forward to every day I spent with Pearl, my life partner. It felt like my early years with Eugénie, when being half of a couple had been as important to her as it was to me. I hoped our happiness would continue forever.

Guatemala by Motorcycle

Leo’s wedding, to a Mexican, was planned for September. I showed Pearl my map of Mexico.

“How about a month on a motorcycle? You will need a hard ass.”

“It will be romantic. But I only get three weeks’ vacation.”

“I can leave before you and return after you. I can reach Mazatlán in four or five days. Then you fly and meet me. We’ll ride to Tepic and stay there for two days for Leo’s wedding. From there, we can reach Guatemala in a week.”

“I saw on TV there is a war there.”

“The war is in the jungle. Tourists on the highway are safe. Is there a sign for Guatemala?” I fingerspelled Guatemala.

“Not in Canada. Just fingerspell it.”

“Maybe this?” To make a sign for Guatemala, I signed the sign for “nervous” but added a “G.”

Pearl chuckled. “Good—easy to remember!”

On departure day, I packed, put on my leathers and helmet, started the engine, and signed. “If you arrive in Mazatlán and I’m not there, go to the Holiday Inn and wait for me.”

Pearl nodded nervously. “I am happy your sister will stay with me while you ride to Mazatlán so you can telephone me through her.”

I kissed Pearl goodbye and rode off.

My friend Virgil’s house, just beyond the Canadian-American border, was my first stop. My bearded friend gave me a gift of a vial of cocaine.

“Two grams. Have the ride of your life.”

I started the engine. Virgil, a motorcyclist himself, hugged me; we knew each ride might be our last. I rode off. A few minutes later, I pulled over and snorted a capful.

On the third afternoon, I reached Tucson. I rented a locker to cache my leathers, warm clothing, and camping gear, and I checked into a motel. After two nights of camping rough, it felt good to shower off 3,000 kilometers of dirt. I called home from a payphone.

“Nadine, I’m in Tucson. Tomorrow I’ll be in Mexico. How’s Pearl?”

“She’s been waiting for your call. She says she loves you.”

“Tell her I love her. The day after tomorrow, I’ll be in Mazatlán before her plane arrives. She doesn’t have to worry. I won’t phone from Mexico. I hope you two had a good time.”

“I got writer’s cramp. I decided to take a sign language—beep!” Our connection dropped as the payphone money ran out.

I rode off at dawn in the chilly morning desert air. Tucson’s lights shrank in the mirrors as the suburbs and farms gave way to sagebrush, saguaro, and mesas. I enjoyed some of the most vivid painted landscapes in the world on the way through Calabasas to the Mexican border. I crossed the border and began riding to Mazatlán. On the two-lane road with no shoulders, disaster lurked around every corner: gravel, oil, potholes, livestock, dogs, trucks, and speed bumps. Vultures perched on roadside carrion.

On the fifth day, I passed the Tropic of Cancer sign. I thought of the photo I had taken of it with Eugénie, when I believed that we would ride together forever.

The road became banked by cornfields, like riding through a slot in a maze. I rode faster to be sure I’d be at the airport before Pearl arrived.

I almost didn’t arrive at all.

A cow walked out from the corn and stood in the center of the road. My tires squealed as I halted, my front wheel just under the cow’s belly. It bellowed and disappeared into the corn on the other side. I rode the last fifty kilometers at a snail’s pace, shaking.

Pearl walked into the arrival hall. She carried the Samsonite holding our formals for the wedding and a bag with her travel gear. She looked nervous and frightened, but when she saw me, the tension drained from her body, and she drooped like a deflated doll. We were both exhausted.

“I was worried. Did you have any problems?”

“Only a cow. Let’s go. Leo and Maria must be waiting for us.”

We walked out of the air-conditioned terminal.

“My God, it’s so hot! Your bike is filthy. Look at the bugs on the front!”

I strapped the Samsonite onto the rack. Under the scorching sun, we put our helmets on and began the 300-kilometer ride to Tepic. The landscape shimmered in the heat, and mirages floated over the superheated asphalt. Up a hill, a black cloud of exhaust fumes blanketed the highway. As we passed through the smoke, I noticed the sign on the back of the truck belching it: Dios permite mi regreso—God allows my return.

An hour later, we pulled into a Pemex station and, after refueling, ate in a roadside café. Flypaper spiraled down from the ceiling over each table. Outside, children pelted a piñata. There was no air-conditioning. For music, we could drop a peso into a Wurlitzer.

“I will show you Mexico. This is my fifth trip.” I pointed to the huevos rancheros on the menu. “Real Mexican food.”

A girl served chillied eggs, refried beans, and Bimbo bread on stoneware. She laid a basket of tortillas wrapped in cloth on the red-and-white tablecloth and returned with mugs of steaming milk. I scooped a teaspoon of Nescafé into each mug. Pearl wiped a finger on her arm, showed me her black fingertip, and stuck out her tongue.

“We will be dirty every day,” I signed.

“You went far in five days.”

“They were long days, but Virgil gave me some cocaine.”

“Motorcycle riding makes me want to pee.”

I handed Pearl some tissue and pointed to a door. She came back a few minutes later.

“It stinks! I couldn’t sit. My legs are tired from squatting. Mexican woman must get constipated.”

“Never! Mexican food prevents constipation.”

We laughed. All eyes in the café followed our signing as we walked to the motorcycle for the final run to Tepic.

As we parked at the Hotel Fray Junipero Serra, I looked up to see McGuire, Leo’s colleague, sitting behind a window and drinking Tecate beer.

“When did you get in?” I shouted.

“Yesterday! I’ve been to Maria’s already. They’re waiting for you. I’m your police escort to the pre-nuptial feast. Delouse yourselves. Call room 314 when you’re done. I’ll try to be drunk by then.”

Pearl and I showered and joined McGuire in a taxi to Maria’s. I interpreted between English and ASL, while Maria interpreted between Spanish and English. Between drinks of brandy, beer, and Canadian Club, which Maria’s father thought wise to have on hand, there were questions about Canada, deafness, and motorcycles. The family and neighbors filled the house and spilled onto the sidewalk.

“¡Salud!” I toasted to Maria’s father.

“Salud, dinero, y amor,” he replied.

“Y el tiempo para gustarlos,” Maria added.

“To health, money, and love,” I said, “and the time to enjoy them.”

Pearl held up her glass. “I have all four.”

In the morning, the five of us went to the beach. We sat on the sand in our bathing suits.

Pearl looked at McGuire’s arm. “A tattoo, not like a cop.”

“McGuire’s a good cop, but he has to wear a long-sleeve shirt,” said Leo.

McGuire pulled bottles of Dos Equis beer from the cooler and studied the labels. “No expiry date—we’d better test them.” He downed a bottle in one quaff. “That one passed.”

“Let me test.” Leo drank a bottle in one go. “You guys better test some, too.”

We swam, ate a picnic lunch, and “tested” the rest of the beer.

The next day, we put on our formals and walked to the cathedral. Leo handed me his camera and asked me to be their photographer. He was married to Maria in Spanish on 11 September, understanding neither the ceremony nor the documents. The reception was happy and drunken. We sat at the head table as guests of honor. The guests pinned money on Leo’s and Maria’s clothes while we danced to pop and mariachi music.

The sign over the bar reminded us Después de el Borracho Viene la Cruda—after the bender, the hangover comes.

In the morning, Pearl and I stored the Samsonite at Maria’s, bade farewell, and headed south. We rode along the coast through Barra de Navidad and stopped in a Playa Azul beachside hotel.

We swam, beachcombed, and sat on our towels on the sand. A waiter brought us margaritas.

“Five hundred kilometers today. Are you still afraid?”

“No. This is romantic. Don’t look—a man on the beach is watching.”

“Your radar is always scanning. Of course, he stares. He never sees sign language.”

“Did you come here before?”

“No. Eugénie and I turned around at Puerto Vallarta.”

“Do you still think about Eugénie?”

“No. At first, it was hard. Remember when you were small, and you didn’t recognize your house when you came home from vacation? I felt like that when Eugénie moved out.”

“I felt like that when I came home from boarding school.”

The man on the beach approached us. We were astonished when he started to sign.

“I don’t understand,” Pearl signed.

I borrowed a pencil and paper from the waiter. The man wrote in Spanish, “Good afternoon. Where are you from?”

“Canada,” I said, startling the man, who had assumed I was deaf.

“Are you going to Mexico City?” he said in Spanish.

“Yes, in two weeks if we have time,” I said in Spanish, then signed.

“There is a deaf café in Mexico City. Everyone there understands sign language. It’s near the Palace of Fine Arts. I recommend it.”

Pearl was excited. “Wonderful! We will look for it.”

“Will you visit my village? I invite you.”

“No, we can’t,” signed Pearl.

“Sorry,” I said in Spanish.

He bade us farewell and walked away.

“He was disappointed. I wanted to go.”

“He will ask for money or steal the motorcycle.”

We started early every morning because a late start would mean a short day, and we had to avoid riding at night. The roadside crucifixes where drivers had died were reminders of the risks we took. We stayed no more than one night in each town. The BMW attracted attention everywhere, as if we were a parade. Pearl amused herself by waving to children, and I often heard her laughing.

We rode to Acapulco, to a resort on the beach. As soon as we spread our towel on the sand, hawkers swarmed around us to sell serapes, towels, sandals, time-share condominiums, and marijuana.

“I feel like I am meat, and they are flies,” Pearl signed.

“They bother hearies and deafies exactly the same.”

She grinned. “Here, we are equal. There were so many children on the road today. My arms are tired from waving. I want to wave at every kid who waves at me.”

A ragged girl followed us as we walked around the town, begging in English, Spanish, and German. I interpreted, but I didn’t look at her. Each time she touched us, we swatted her hand away.

Finally, Pearl could take no more. “What do you want?” I did not interpret.

The girl held out her hand, palm up, with an irresistible smile. I put a coin in it. She walked away, thinking we were deaf.

“You should not give money,” Pearl signed.

“She may be beaten if she gets nothing. It’s just a peso. Let’s have dinner and eat well here. This is our last beach stop for a while.”

In Oaxaca, we were stopped at a military checkpoint. “Pasaporte,” demanded an officer. He thumbed through our passports and asked me if we had guns. I said no. We would be stopped at checkpoints every two hours for the next four days.

The state of Chiapas seemed like another country. We entered the rainforest. Women with naked breasts walked on the

Comments (0)