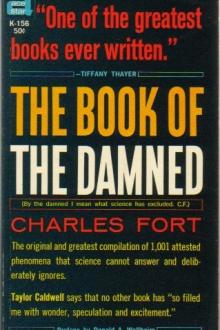

The Book of the Damned by Charles Fort (reading women TXT) 📖

- Author: Charles Fort

- Performer: -

Book online «The Book of the Damned by Charles Fort (reading women TXT) 📖». Author Charles Fort

Something poured electricity upon them.

The stones of these forts exist to this day, vitrified, or melted and turned to glass.

The archaeologists have jumped from one conclusion to another, like the "rapid chamois" we read of a while ago, to account for vitrified forts, always restricted by the commandment that unless their conclusions conformed to such tenets as Exclusionism, of the System, they would be excommunicated. So archaeologists, in their medieval dread of excommunication, have tried to explain vitrified forts in terms of terrestrial experience. We find in their insufficiencies the same old assimilating of all that could be assimilated, and disregard for the unassimilable, conventionalizing into the explanation that vitrified forts were made by prehistoric peoples who built vast fires—often remote from wood-supply—to melt externally, and to cement together, the stones of their constructions. But negativeness always: so within itself a science can never be homogeneous or unified or harmonious. So Miss Russel, in the Journal of the B.A.A., has pointed out that it is seldom that single stones, to say nothing of long walls, of large houses that are burned to the ground, are vitrified.

If we pay a little attention to this subject, ourselves, before starting to write upon it, which is one of the ways of being more nearly real than oppositions so far encountered by us, we find:

That the stones of these forts are vitrified in no reference to cementing them: that they are cemented here and there, in streaks, as if special blasts had struck, or played, upon them.

Then one thinks of lightning?

Once upon a time something melted, in streaks, the stones of forts on the tops of hills in Scotland, Ireland, Brittany, and Bohemia.

Lightning selects the isolated and conspicuous.

But some of the vitrified forts are not upon tops of hills: some are very inconspicuous: their walls too are vitrified in streaks.

Something once had effect, similar to lightning, upon forts, mostly on hills, in Scotland, Ireland, Brittany, and Bohemia.

But upon hills, all over the rest of the world, are remains of forts that are not vitrified.

There is only one crime, in the local sense, and that is not to turn blue, if the gods are blue: but, in the universal sense, the one crime is not to turn the gods themselves green, if you're green.

13One of the most extraordinary of phenomena, or alleged phenomena, of psychic research, or alleged research—if in quasi-existence there never has been real research, but only approximations to research that merge away, or that are continuous with, prejudice and convenience—

"Stone-throwing."

It's attributed to poltergeists. They're mischievous spirits.

Poltergeists do not assimilate with our own present quasi-system, which is an attempt to correlate denied or disregarded data as phenomena of extra-telluric forces, expressed in physical terms. Therefore I regard poltergeists as evil or false or discordant or absurd—names that we give to various degrees or aspects of the unassimilable, or that which resists attempts to organize, harmonize, systematize, or, in short, to positivize—names that we give to our recognitions of the negative state. I don't care to deny poltergeists, because I suspect that later, when we're more enlightened, or when we widen the range of our credulities, or take on more of that increase of ignorance that is called knowledge, poltergeists may become assimilable. Then they'll be as reasonable as trees. By reasonableness I mean that which assimilates with a dominant force, or system, or a major body of thought—which is, itself, of course, hypnosis and delusion—developing, however, in our acceptance, to higher and higher approximations to realness. The poltergeists are now evil or absurd to me, proportionately to their present unassimilableness, compounded, however, with the factor of their possible future assimilableness.

We lug in the poltergeists, because some of our own data, or alleged data, merge away indistinguishably with data, or alleged data, of them:

Instances of stones that have been thrown, or that have fallen, upon a small area, from an unseen and undetectable source.

London Times, April 27, 1872:

"From 4 o'clock, Thursday afternoon, until half past eleven, Thursday night, the houses, 56 and 58 Reverdy Road, Bermondsey, were assailed with stones and other missiles coming from an unseen quarter. Two children were injured, every window broken, and several articles of furniture were destroyed. Although there was a strong body of policemen scattered in the neighborhood, they could not trace the direction whence the stones were thrown."

"Other missiles" make a complication here. But if the expression means tin cans and old shoes, and if we accept that the direction could not be traced because it never occurred to anyone to look upward—why, we've lost a good deal of our provincialism by this time.

London Times, Sept. 16, 1841:

That, in the home of Mrs. Charton, at Sutton Courthouse, Sutton Lane, Chiswick, windows had been broken "by some unseen agent." Every attempt to detect the perpetrator failed. The mansion was detached and surrounded by high walls. No other building was near it.

The police were called. Two constables, assisted by members of the household, guarded the house, but the windows continued to be broken "both in front and behind the house."

Or the floating islands that are often stationary in the Super-Sargasso Sea; and atmospheric disturbances that sometimes affect them, and bring things down within small areas, upon this earth, from temporarily stationary sources.

Super-Sargasso Sea and the beaches of its floating islands from which I think, or at least accept, pebbles have fallen:

Wolverhampton, England, June, 1860—violent storm—fall of so many little black pebbles that they were cleared away by shoveling (La Sci. Pour Tous, 5-264); great number of small black stones that fell at Birmingham, England, August, 1858—violent storm—said to be similar to some basalt a few leagues from Birmingham (Rept. Brit. Assoc., 1864-37); pebbles described as "common water-worn pebbles" that fell at Palestine, Texas, July 6, 1888—"of a formation not found near Palestine" (W.H. Perry, Sergeant, Signal Corps, Monthly Weather Review, July, 1888); round, smooth pebbles at Kandahor, 1834 (Am. J. Sci., 1-26-161); "a number of stones of peculiar formation and shapes, unknown in this neighborhood, fell in a tornado at Hillsboro, Ill., May 18, 1883." (Monthly Weather Review, May, 1883.)

Pebbles from aerial beaches and terrestrial pebbles as products of whirlwinds, so merge in these instances that, though it's interesting to hear of things of peculiar shape that have fallen from the sky, it seems best to pay little attention here, and to find phenomena of the Super-Sargasso Sea remote from the merger:

To this requirement we have three adaptations:

Pebbles that fell where no whirlwind to which to attribute them could be learned of:

Pebbles which fell in hail so large that incredibly could that hail have been formed in this earth's atmosphere:

Pebbles which fell and were, long afterward, followed by more pebbles, as if from some aerial, stationary source, in the same place. In September, 1898, there was a story in a New York newspaper, of lightning—or an appearance of luminosity?—in Jamaica—something had struck a tree: near the tree were found some small pebbles. It was said that the pebbles had fallen from the sky, with the lightning. But the insult to orthodoxy was that they were not angular fragments such as might have been broken from a stony meteorite: that they were "water-worn pebbles."

In the geographical vagueness of a mainland, the explanation "up from one place and down in another" is always good, and is never overworked, until the instances are massed as they are in this book: but, upon this occasion, in the relatively small area of Jamaica, there was no whirlwind findable—however "there in the first place" bobs up.

Monthly Weather Review, August, 1898-363:

That the government meteorologist had investigated: had reported that a tree had been struck by lightning, and that small water-worn pebbles had been found near the tree: but that similar pebbles could be found all over Jamaica.

Monthly Weather Review, September, 1915-446:

Prof. Fassig gives an account of a fall of hail that occurred in Maryland, June 22, 1915: hailstones the size of baseballs "not at all uncommon."

"An interesting, but unconfirmed, account stated that small pebbles were found at the center of some of the larger hail gathered at Annapolis. The young man who related the story offered to produce the pebbles, but has not done so."

A footnote:

"Since writing this, the author states that he has received some of the pebbles."

When a young man "produces" pebbles, that's as convincing as anything else I've ever heard of, though no more convincing than, if having told of ham sandwiches falling from the sky, he should "produce" ham sandwiches. If this "reluctance" be admitted by us, we correlate it with a datum reported by a Weather Bureau observer, signifying that, whether the pebbles had been somewhere aloft a long time or not, some of the hailstones that fell with them, had been. The datum is that some of these hailstones were composed of from twenty to twenty-five layers alternately of clear ice and snow-ice. In orthodox terms I argue that a fair-sized hailstone falls from the clouds with velocity sufficient to warm it so that it would not take on even one layer of ice. To put on twenty layers of ice, I conceive of something that had not fallen at all, but had rolled somewhere, at a leisurely rate, for a long time.

We now have a commonplace datum that is familiar in two respects:

Little, symmetric objects of metal that fell at Orenburg, Russia, September, 1824 (Phil. Mag., 4-8-463).

A second fall of these objects, at Orenburg, Russia, Jan. 25, 1825 (Quar. Jour. Roy. Inst., 1828-1-447).

I now think of the disk of Tarbes, but when first I came upon these data I was impressed only with recurrence, because the objects of Orenburg were described as crystals of pyrites, or sulphate of iron. I had no notion of metallic objects that might have been shaped or molded by means other than crystallization, until I came to Arago's account of these occurrences (Œuvres, 11-644). Here the analysis gives 70 per cent. red oxide of iron, and sulphur and loss by ignition 5 per cent. It seems to me acceptable that iron with considerably less than 5 per cent. sulphur in it is not iron pyrites—then little, rusty iron objects, shaped by some other means, have fallen, four months apart, at the same place. M. Arago expresses astonishment at this phenomenon of recurrence so familiar to us.

Altogether, I find opening before us, vistas of heresies to which I, for one, must shut my eyes. I have always been in sympathy with the dogmatists and exclusionists: that is plain in our opening lines: that to seem to be is falsely and arbitrarily and dogmatically to exclude. It is only that exclusionists who are good in the nineteenth century are evil in the twentieth century. Constantly we feel a merging away into infinitude; but that this book shall approximate to form, or that our data shall approximate to organization, or that we shall approximate to intelligibility, we have to call ourselves back constantly from wandering off into infinitude. The thing that we do, however, is to make our own outline, or the difference between what we include and what we exclude, vague.

The crux here, and the limit beyond which we may not go—very much—is:

Acceptance that there is a region that we call the Super-Sargasso Sea—not yet fully accepted, but a provisional position that has received a great deal of support—

But is it a part of this earth, and does it revolve with and over this earth—

Or does it flatly overlie this earth, not revolving with and over this earth—

That this earth does not revolve, and is not round, or roundish, at all, but is continuous with the rest of its system, so that, if one could break away from the traditions of the geographers, one might walk and walk, and come to Mars, and then find Mars continuous with Jupiter?

I suppose some day such queries will sound absurd—the thing will be so obvious—

Because it is very difficult for me to conceive of little metallic objects hanging precisely over a small town in Russia, for

Comments (0)