The Bungalow Boys Along the Yukon by John Henry Goldfrap (red white royal blue txt) 📖

- Author: John Henry Goldfrap

- Performer: -

Book online «The Bungalow Boys Along the Yukon by John Henry Goldfrap (red white royal blue txt) 📖». Author John Henry Goldfrap

"Look out there, Sandy!" warned Tom, knowing the boy's remarkable faculty for getting into trouble.

"Hoot toot! Dinna fash yersel' aboot me," returned Sandy easily, and set another rock rolling and bounding down the glacier.

As if in bravado, he clambered right up on the smooth cliff before his companions could check him. But at that instant his foot caught on a rock and he stumbled and fell.

Tom jumped forward to save him, but the lad's clothes tore from his grasp, as Sandy shot downward at a terrific speed, at the same time emitting a wild shriek of terror.

At the same instant his cry was echoed by Jack, for Tom, who had in vain sought to save his chum, now shared Sandy's misfortune and went chuting downward to the river on the smooth rock chute at lightning speed.

"Help!" cried Jack, as if human aid could accomplish anything, "help! They'll both be killed."

"Ki-i-i-i-i-l-l-e-d!" flung back the mocking echoes from the cliffs.

CHAPTER XX.DOWN THE GLACIER.

Sandy's wild shout of alarm caused the gentlemen on the deck of the Yukon Rover to start up in affright.

They looked above them and what they saw was sufficiently alarming. Two boys, rolling and tumbling down the smooth rock slope, bound straight for the river! So swiftly did it all happen that they had hardly time to realize the catastrophe that had overtaken the boys, before the two victims of this double disaster struck the water with a splash and vanished from view.

"Quick, Chillingworth! The life preservers!" cried Mr. Dacre running to where they were kept. He flung all he could lay his hands on far out toward the spot where the glacier dipped into the water. In another instant, to the unspeakable relief of both men, they saw two heads come to the surface.

But on Sandy's head was a broad cut, and though he struck out toward the nearest life preserver, his efforts were feeble. It was evident that he had been injured in his fall, but how badly, of course, they could not tell. Tom was striking out with strong, swift movements. He had seized one of the life preservers, when he perceived Sandy's plight. Instantly dropping the ring, he struck out for the Scotch lad.

Just as he reached his chum's side, the rushing current caught both boys in its grip and hurtled them out toward the middle of the stream. So swiftly did it run that, despite Tom's strong strokes, he could not gain an inch on the body of his chum, which was being borne like something inanimate down the stream.

The gentlemen on the deck of the Yukon Rover watched this scene with fascinated horror. Powerless to aid, all they could do was to watch the outcome of this drama.

In the meantime, Jack, pale with fright, was coming down the steep cliffside in leaps and bounds. He had not seen his brother and his comrade rise and did not know but that they had not reappeared at all.

Tom felt the current grip him like a giant's embrace. He had been partially stunned by the swiftness of his flight down the steep, precipitous glacier, but the plunge into the cold waters of the river had revived him. When he had risen to the surface after his plunge, he was in full possession of all his faculties. To his delight he was not injured, and almost the first thing he saw near him was Sandy's head.

As we know, he struck out for it, only to have his chum snatched almost out of his very arms by the mighty sweep of the current.

Like those on the steamboat, he had seen the cut over Sandy's eye and knew that he was injured. This made Tom all the more feverishly anxious to catch up with him, for although Sandy was a strong and good swimmer and had plenty of presence of mind in the water, if he was seriously hurt it was not probable he could stay long above the surface.

But Tom speedily found that, try as he would, he could make no gain on his chum. He heard Sandy cry out despairingly as the current swept him round a bend. The next instant Tom realized that not far below them lay some cruel rapids which the Yukon Rover had bucked that afternoon with the greatest difficulty. He knew that if something didn't happen before they got into the grip of that boiling, seething mass of water, their doom was sealed.

He almost fancied as he drifted along, allowing the current to carry him and saving his strength for the struggle he knew must come, that he could already hear the roaring voice of the rapids and see the white water whipping among the jagged black rocks, contact with which would mean death.

It was at this instant that he spied something that gave him a gleam of hope. Right ahead of them there loomed up a possible chance that he had forgotten. It was one of those willowy islets that have been mentioned as dotting the Yukon for almost its entire length. If he could but gain that, if some lucky sweep of the current would but carry Sandy in among the trees, both their lives might be saved.

And now the river played one of those freaks that rapidly running streams containing a great volume of water frequently do. Sandy's body was swept off into a sort of side eddy, while Tom felt himself seized by an irresistible force and rushed forward in the grip of the tide as it roared down to the rapids.

Horror at his utter incapacity to stem it or to do aught but yield to the rush of the stream, rendered him almost senseless for an instant. In his imagination his body was already being battered in the rapids and flung hither and thither in the boiling whirlpools.

But suddenly an abrupt collision that almost knocked the breath out of his body gave him something else to think of. Twigs brushed and scratched his face and he was held fast by branches. With a swift throb of thankfulness he realized the next instant that the impossible had happened.

A vagary of the current had swung him into the midst of the willow island and he was anchored safely in the branches of one of the trees. But he gave himself little time to think over this. His thoughts were of Sandy. Where was the Scotch boy?

Had he been swept on down the river to the rapids or had he sunk? Hardly had these questions time to flash through his mind, when he gave a gasp and felt his heart leap.

Coming toward him, and not more than a few feet away, was a dark object that he knew to be Sandy's head. The next instant he saw the boy's appealing eyes.

Sandy had seen him, too, as the same current that had caught Tom in its embrace hurtled his chum down the river.

"Tom!" he cried. "Tom!"

Tom made no reply.

It was no time for words. He quickly judged with his eye the spot where Sandy must be borne by him, and clambered out upon a branch overhanging the water. His object was to save his chum, but it must be confessed that his chances of doing so looked precarious.

The limb upon which he had climbed was, in the first place, not a branch in which much confidence could be consistently placed. It was to all appearances rotten, although it bore his weight. But it was no time to weigh chances. The stream was bearing Sandy down upon the willow island, and Tom realized that, unless the boy was carried into the midst of the clump as he had been, he would hardly have strength enough left to grab a projecting branch and thus save himself from the grip of the river.

He had hardly made up his mind to the plan he would pursue when Sandy was right upon him. But he was further out than Tom had calculated. However, Tom had anticipated this possibility and throwing himself flat on the limb, he twisted his legs around it and reached out, with an inward prayer that he might be successful in the struggle that was to ensue between himself and the mighty Yukon.

As Sandy shot by, Tom's arms enveloped him. The pull of the current was stronger than he thought, but he held on for dear life, his face almost touching the rushing waters. He was drawing Sandy in toward him and in another instant both would have been safe, when there was an ominous "crack!"

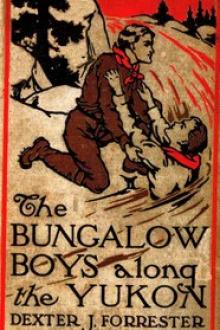

Throwing himself flat on the limb … he reached out. (Page 200)

The branch had parted under the double strain!

In a moment both boys were caught in the clutch of the current of the swiftly flowing "Golden River."

CHAPTER XXI.THE GRIP OF THE YUKON.

The moments that followed were destined to be burned for his lifetime into Tom's brain. Half choked, sputtering, blinded by spray and spume, he found himself in the water with Sandy, completely exhausted by this time, to care for as well as himself. The Scotch boy lay like a dead burden on Tom's arm, and it was all that he could do to keep him afloat and still keep his own head above water.

Suddenly something struck him on the back of the head. It was the branch that had snapped off and cast them into the wild waters. But Tom at that moment hailed it as an aid and caught hold of it with his free arm. It was a large limb and to his delight he found that it kept them afloat, aided by his skillful treading of water.

But barely had he time to rejoice in this discovery, when the roar of the rapids ahead of them caused his brain to swim dizzily with fear. He knew that in the center of the rapids was a comparatively wide, smooth channel through which they had ascended that afternoon in the Yukon Rover.

If the current shot them through this, there was still a chance that they might live, slender though that hope appeared to be. But on either side of this channel, if such it could be called, there uprose rocks like black, jagged fangs in and amongst which the water boiled and swirled and undersucked with the voice of a legion of witches. It was into one of these maelstroms that poor Tom was confident they were being borne.

Now the sound of the rapids grew louder. They roared and rumbled like the noise of a giant spinning factory in full operation. The noise was deafening and to Tom's excited ears it sounded like the shrill laughter of malign fates. Suddenly something dragged at his legs. It felt as if some monster of the river had risen from its depths and had seized him.

But Tom knew it was no living creature. It was something far more terrible,—the undertow.

He caught himself wondering if this were the end, as he was sucked under and the water closed over his head with a roar like that of a thousand cataracts.

His lungs seemed bursting, his ear drums felt as if an intolerable weight was pressing in upon them. Tom was sure he could not have lasted another second, when he was suddenly shot to the surface with the same abruptness with which he had been drawn under.

Ahead of him were two rocks between which the pent up river rushed like an express train. Tom had just time to observe this and figure in a dull way that he and Sandy would be dragged through that narrow passage to a miserable death, when something

Comments (0)