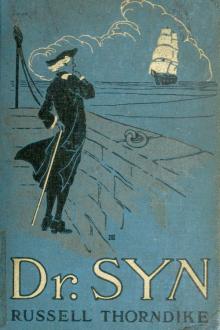

Doctor Syn by Russell Thorndyke (10 best novels of all time .txt) 📖

- Author: Russell Thorndyke

- Performer: -

Book online «Doctor Syn by Russell Thorndyke (10 best novels of all time .txt) 📖». Author Russell Thorndyke

[Signed] Scarecrow.

With this useful letter tucked away in her blouse in company with one of Mrs. Waggetts’ pistols, Imogene, after bidding farewell to the two fishermen, struck out from the beach across the mile or so of flat country that lies in front of the little rising town of Rye. It is a fortified town, an ancient stronghold against whose walls the sea at one time used to beat but has long since receded. Her heart beat high as she looked up at the great battlements and the quaint little houses that clustered in all shapes and sizes around them, higher and higher, until they reached the church tower, the highest point of all.

She did not enter the town by the north gate, but skirted the wall and ascended the long irregular stepway that rises from the river wharf—a long ladder of stone that climbs the surface of rock zigzag till you find yourself at the top of the wall and standing upon the cobbled roadway of Watchbell Street—a thoroughfare made green with moss and with rank grass and rendered vastly attractive by the picturesque houses that flank its little pavements. To one of these little houses

Imogene made her way, a little white house with a quaint little white front door. She pulled the brass chain, and in response to the bell a serving-maid announced that Mr. Whyllie was not then at home, having gone to church with his wife. So perforce she had to wait until the master and mistress returned from the morning service. A quaint old lady was the wife of the starchy old law^^er. She was dressed in highly flowered brocades, with a curious bonnet, under which her round little face shone out with much animation. A clever little face it was, with a queer little pursed-up mouth, and a tiny little nose with an upward tilt, and her eyes were lively. It was the face of a clever eccentric. Imogene saw them coming and gave them a profound courtesy as they drew near to their front door.

“Lord love you, Mister Whyllie,” the old lady exclaimed, “and what’s the pretty wench bobbing at us for?”

“It may be that she would speak to you, my dear,” replied the lawyer to his wife.

“Then why doesn’t she, sir?” answered the little lady, raising her glasses and quizzing Imogene from head to foot. “A handsome face she has, Mister Whyllie, a handsome face indeed, refined yet rough, but then again rough yet refined, take it how you will, but Lord love you again, Mister Whyllie, she has positively the most obnoxious clothes you could wish for to meet, and no shoes, neither has she stockings, sir, but shapely legs, sir, good legs indeed, though you need not embarrass the child by quizzing them, Mister Whyllie.”

Mr. Whyllie looked away awkwardly and, raising his hat, inquired whether Imogene wished to speak to them.

“I have come to speak to you, sir, on most grave business.”

“To do with one of my cases, I suppose,” he answered, by way of explanation, to his wife, for he had no wish that she should suspect him of having any dealings with such a handsome wench.

“Which case?” snapped the suspicious little wife.

“Well, really, now, I cannot say off hand,” faltered the lawyer. “Probably the Appledore land claims, but I wouldn’t swear to it, for it could quite equally be something to do with the Canver squabble. In fact, more likely to be, quite likely to be. Probably is, probably is. It might so very well be that, mightn’t it, my love?”

“Yes, and it might not be that,” returned his wife with scorn. “Why don’t you ask the girl if you want to know, instead of standing there like the town idiot? Being a lawyer, I naturally suppose you to have a tongue in your head.”

“I have, my dear,” exclaimed the lawyer desperately, “but dang it, ma’am, you will not let me wag it.”

“You blasphemous horror!” screamed the lady, sweeping past him into the house, for the serving-maid was holding the front door open for them.

It was, by the way, a good thing for Antony Whylie that his house was situated in a quiet corner of Watchbell Street, a very good thing, for these sudden squalls would repeatedly burst from his wife, regardless altogether of publicity.

With a sigh the attorney begged Imogene to follow him, and led the way into a little breakfast-room whose latticed windows looked out upon the street. It was a panelled room, but the panels were enamelled with white paint, which gave to the place a most cheerful aspect. Upon each panel hung a mahogany framed silhouette portrait of some worthy relative and over each panel was hung a brass spoon or brazen chestnut roaster, each one polished like gold and affording a bright contrast to the black portraits below, which stood out so very severely against the white panelling. There was in one corner of the room an embrasure filled with shelves, the shelves in their turn being filled with china. A round mahogany table, mahogany chairs, and a heraldic mantelpiece made up the rest of the furniture of this altogether delightful little room into which Imogene followed the lawyer, who placed a chair for her and shut the door. He then sat down by the fire and awaited her pleasure to address him. Imogene handed him the paper which had been prepared for her, and as he began to read she drew the silver pistol from her blouse and held it ready beneath a fold of her dress. That the lawyer was greatly startled was only too plain, for as he read the letter he turned a terribly pallid colour in the face.

“God bless me! but it’s monstrous,” he said, starting up, with his eyes still on the paper. “Not content with holding up my coach, commandeering my horses, and making me look extremely ridiculous, they now force me, a lawyer, an honest lawyer, to break those very laws that I have sworn to defend. It’s monstrous! Utterly monstrous! What am I to do? What can I do? My wife must know of this! My wife must read this letter,” and accordingly he took a step toward the door. But Imogene was too quick for him. With her back against it and the pistol levelled at his head, the lawyer was entirely nonplussed.

“If you please, sir,” she said, “I had orders that you were not to leave the room, indeed that you were not to leave my sight, until I was quite satisfied that you would carry out the Scarecrow’s orders.”

“No, really?” exclaimed the lawyer.

“Yes, indeed, sir,” replied the girl, and then added in a frightened voice: “If you disobey the Scarecrow, it is just as well that I should shoot you here, for all the chance you will have to get away from the penalty, and for myself—well, the consequences would be as fatal to me in either case, so you see if you do not help me by obeying the letter you will not only be killing yourself but me, too.”

The lawyer looked blankly at Imogene, and then, retreating from the close and unpleasant proximity of the pistol, sank into his armchair.

“Put it down, girl! Put that pistol down for heaven’s sake, for how can I think whilst I am being made a target of?”

Imogene lowered the weapon.

“I really don’t know what to say,” went on the wretched old man. “I am entirely fogged out of all vision. Muddled, muddled—entirely muddled. I wish you would let my wife come in. Oh, how I do wish you would! Miatever her faults may be, she is really most excellent at thinking out difficulties of this kind. In fact, I must confess that she does all my thinking work for me. Women sometimes, you know, have most excellent brains—quick brains. They have, you know. Really they have. Quick tongues, too. My wife has. Oh, yes, really, you know, she’s got both, and the tongue part of her is developed to a most astonishing degree. But give her her due. Give her her due. So’s her brain. So’s her brain. A most clever brain—most clever. Very quick; exceptionally alert. As clever as a man, really she is. In fact, she’s absolutely cleverer than most. She’s cleverer than me. Oh, yes, she is. I confess it. I’m not conceited. Why, she does all my work for me—so there you are. It proves it, don’t it? Writes all my speeches for me. Really, you know, I am utterly useless without her. She guides me—absolutely guides me, she does. “VMiy, alone I’m hopeless. How on earth do you suppose that I can get a young man out of the hands of the Rye press gang? They’re the most desperate of ruffians. The most desperate set of good-for-noughts that you could possibly wish to meet.”

The handle of the door turned suddenly, but Imogene’s foot was not easily shifted.

“There’s something in the way of the door, you clumsy clodhopper!” called the voice of Mrs. Why Hie from outside.

“I know there is, my love,” faltered the husband, and then to Imogene he said: “Oh, please let her come in. She will be quiet, I’m sure.” Then in a louder tone: “You will be quiet, won’t you, my love?”

“Antony,” called the voice of the spouse, “are you addressing yourself to that handsome girl? Are you calling her your love?” Then in a tone of doom: “Wait till I get in!”

“Oh, dear, oh, dear, she’s misunderstanding me again. Don’t let her come in now, for heaven’s sake!” But Imogene had already opened the door and in had burst the little lady, and without heeding Imogene she rushed across the room and administered with her mittened hand a very resounding and sound box upon her husband’s ear.

“Now perhaps you will behave yourself like a respectable married man, like an old fogey that you are, like everything in fact that you ought to be, but aren’t and never will be! Will you behave yourself now, you truly terrible old man?”

“Certainly, my love,” meekly replied the lawyer, “but do look at this young lady.”

“Sakes alive!” she exclaimed when she did look at Imogene, “for if she hasn’t got a pistol in her hand, you’re no fool, Antony!”

“She has got a pistol in her hand, my love, and I’ll not only be a fool, but a dead fool, if you don’t find some way out of the difficulty.”

“And what is the difficulty, pray?” she asked, looking from her terrified husband to the extraordinary girl. “Oh, keep that pistol down, will you, my dear? for there is no immediate danger of my eating you. Just because I keep this fool of a husband of mine in his place, you mustn’t think me an utter virago.”

“I am afraid it is me that you will be thinking a virago,” answered the girl, still feigning fear in her voice, “but indeed I cannot help

Comments (0)