Genre Fairy Tale. Page - 10

es really did send for the doctor, who came briskly in, just as Elizabeth Ann had always seen him, with his little square black bag smelling of leather, his sharp eyes, and the air of bored impatience which he always wore in that house. Elizabeth Ann was terribly afraid to see him, for she felt in her bones he would say she had galloping consumption and would die before the leaves cast a shadow. This was a phrase she had picked up from Grace, whose conversation, perhaps on account of her asthma, was full of references to early graves and quick declines.

And yet--did you ever hear of such a case before?--although Elizabeth Ann when she first stood up before the doctor had been quaking with fear lest he discover some deadly disease in her, she was very much hurt indeed when, after thumping her and looking at her lower eyelid inside out, and listening to her breathing, he pushed her away with a little jerk and said: "There's nothing in the world the matter with that child. She's as sound as a nut! What sh

nough to tease.

'Look here,' said Anthea. 'Let's have a palaver.' This worddated from the awful day when Cyril had carelessly wished thatthere were Red Indians in England--and there had been. The wordbrought back memories of last summer holidays and everyonegroaned; they thought of the white house with the beautifultangled garden--late roses, asters, marigold, sweet mignonette,and feathery asparagus--of the wilderness which someone had oncemeant to make into an orchard, but which was now, as Father said,'five acres of thistles haunted by the ghosts of babycherry-trees'. They thought of the view across the valley, wherethe lime-kilns looked like Aladdin's palaces in the sunshine, andthey thought of their own sandpit, with its fringe of yellowygrasses and pale-stringy-stalked wild flowers, and the littleholes in the cliff that were the little sand-martins' littlefront doors. And they thought of the free fresh air smelling ofthyme and sweetbriar, and the scent of the wood-smoke from theco

said Polly, decidedly. "I'd have two hundred,all in a row!"

"Two hundred candles!" echoed Joel, in amazement. "Mywhockety! what a lot!"

"Don't say such dreadful words, Joel," put in Polly, nervously,stopping to pick up her spool of basting thread that was racingaway all by itself; "tisn't nice."

"Tisn't worse than to wish you'd got things you haven't," retortedJoel. "I don't believe you'd light 'em all at once," he added,incredulously.

"Yes, I would too!" replied Polly, reckessly; "two hundred of 'em,if I had a chance; all at once, so there, Joey Pepper!"

"Oh," said little Davie, drawing a long sigh. "Why, 'twould be justlike heaven, Polly! but wouldn't it cost money, though!"

"I don't care," said Polly, giving a flounce in her chair, whichsnapped another thread; "oh dear me! I didn't mean to, mammy;well, I wouldn't care how much money it cost, we'd have as muchlight as we wanted, for once; so!"

"Mercy!" said Mrs. Pepper, "you'd have the house afire! Twohundred candles! who

me may be rotten;

But if twenty for accidents should be detach'd,

It will leave me just sixty sound eggs to hatch'd.

"Well, sixty sound eggs--no; sound chickens, I mean;

Of these some may die--we'll suppose seventeen--

Seventeen!--not so many--say ten at the most,

Which will leave fifty chickens to boil or to roast.

"But then there's their barley; how much will they need?

Why they take but one grain at a time when they feed,

So that's a mere trifle; now then let us see,

At a fair market price, how much money there'll be?

"Six shillings a pair--five--four--three-and-six,

To prevent all mistakes, that low price I will fix;

Now what will that make? fifty chickens, I said,

Fifty times three-and-sixpence--_I'll ask brother Ned_.

"Oh! but stop--three-and-sixpence a _pair_ I must sell 'em; Well, a pair is a couple--now then let us tell 'em;

A couple in fifty will go--(my poor brain!)

Why just a score times, and five pair will remain.

How Benjamin Franklin Came to Philadelphia

After Penn left his colony there was frequent trouble between the Governors and the people. Some of the Governors were untrustworthy, some were weak, none was truly great. But about ten years after Penn's death a truly great man came to Philadelphia. This was Benjamin Franklin. Of all the men of colonial times Franklin was the greatest.

Benjamin was the fifteenth child of his father, a sturdy English Nonconformist who some years before had emigrated from Banbury in England to Boston in America. As the family was so large the children had to begin early to earn their own living. So at the age of ten Benjamin was apprenticed to his own father, who was a tallow chandler, and the little chap spent his days helping to make soap and "dips" and generally making himself useful.

But he did not like it at all. So after a time he was apprenticed to his elder brother James, who had a printing press, and published a little newspaper called the Courant. Benjamin liked that much better. He soon became a good printer, he was able to get hold of books easily, and he spent his spare time reading such books as the "Pilgrim's Progress" and the "Spectator." Very soon too he took to writing, and became anxious to have an article printed in his brother's paper.

But as he was only a boy he was afraid that if his brother knew he had written the article he would never print it. So he disguised his handwriting, and slipped his paper under the

a handsome man of twenty-eight or thirty, with anattractive hint of wickedness in his manner that was sure to make himadorable with good young women. The large dark eyes that lit hispale face expressed this wickedness strongly, though such was theadaptability of their rays that one could think they might haveexpressed sadness or seriousness just as readily, if he had had amind for such.

An old and deaf lady who was present asked Captain Maumbry bluntly:'What's this we hear about you? They say your regiment is haunted.'

The Captain's face assumed an aspect of grave, even sad, concern.'Yes,' he replied, 'it is too true.'

Some younger ladies smiled till they saw how serious he looked, whenthey looked serious likewise.

'Really?' said the old lady.

'Yes. We naturally don't wish to say much about it.'

'No, no; of course not. But--how haunted?'

'Well; the--THING, as I'll call it, follows us. In country quartersor town, abroad or at home, it's just the same.'

'How do you account

gave Tom a hug and greeted Bud warmly. Over the delicious dinner, the conversation turned to the mysterious thief missile.

"Who on earth could have fired it?" Sandy asked.

Tom shrugged. "No telling--yet. There's more than one unfriendly country which would give a lot for the data picked up on our Jupiter shot."

"You aren't expecting more trouble, are you?" Phyl put in uneasily.

Tom passed the question off lightly in order not to alarm his mother and the two girls. But inwardly he was none too sure of what his survey expedition might encounter in trying to locate the lost probe missile.

Ever since his first adventure in his Flying Lab, the youthful inventor had been involved in many daring exploits and thrilling situations. Time and again, Tom had had to combat enemy spies and vicious plotters bent on stealing the Swifts' scientific secrets.

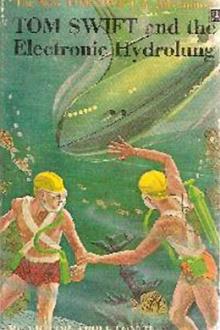

His research projects had taken him far into outer space and into the depths of the ocean. With his atomic earth blaster, Tom ha

tion.

This was because of the promises he had made to his father, andthey had been the first thing he remembered. Not that he hadever regretted anything connected with his father. He threw hisblack head up as he thought of that. None of the other boys hadsuch a father, not one of them. His father was his idol and hischief. He had scarcely ever seen him when his clothes had notbeen poor and shabby, but he had also never seen him when,despite his worn coat and frayed linen, he had not stood outamong all others as more distinguished than the most noticeableof them. When he walked down a street, people turned to look athim even oftener than they turned to look at Marco, and the boyfelt as if it was not merely because he was a big man with ahandsome, dark face, but because he looked, somehow, as if he hadbeen born to command armies, and as if no one would think ofdisobeying him. Yet Marco had never seen him command any one,and they had always been poor, and shabbily dressed, and oftenenou

e blue wavesof the great Pacific. A little way behind them was the house, a neatframe cottage painted white and surrounded by huge eucalyptus andpepper trees. Still farther behind that--a quarter of a mile distantbut built upon a bend of the coast--was the village, overlooking apretty bay.

Cap'n Bill and Trot came often to this tree to sit and watch theocean below them. The sailor man had one "meat leg" and one "hickoryleg," and he often said the wooden one was the best of the two. OnceCap'n Bill had commanded and owned the "Anemone," a trading schoonerthat plied along the coast; and in those days Charlie Griffiths, whowas Trot's father, had been the Captain's mate. But ever since Cap'nBill's accident, when he lost his leg, Charlie Griffiths had beenthe captain of the little schooner while his old master livedpeacefully ashore with the Griffiths family.

This was about the time Trot was born, and the old sailor becamevery fond of the baby girl. Her real name was Mayre, but when shegrew big