Genre Fairy Tale. Page - 20

call her superstitious. She has an odd belief in dreams and we have not been able to laugh it out of her. I must own, too, that some of her dreams--but there, it would not do to let Gilbert hear me hinting such heresy. What have you found of much interest, Susan?" Susan had given an exclamation. "Listen to this, Mrs. Dr. dear. 'Mrs. Sophia Crawford has given up her house at Lowbridge and will make her home in future with her niece, Mrs. Albert Crawford.' Why that is my own cousin Sophia, Mrs. Dr. dear. We quarrelled when we were children over who should get a Sunday-school card with the words 'God is Love,' wreathed in rosebuds, on it, and have never spoken to each other since. And now she is coming to live right across the road from us." "You will have to make up the old quarrel, Susan. It will never do to be at outs with your neighbours." "Cousin Sophia began the quarrel, so she can begin the making up also, Mrs. Dr. dear," said Susan loftily. "If she does I hope I am a good enough Christian to meet her ha

says it would hurt Aunt Martha's feelings. Anne dearie,believe me, the state of that manse is something terrible.Everything is thick with dust and nothing is ever in its place.And we had painted and papered it all so nice before they came."

"There are four children, you say?" asked Anne, beginning tomother them already in her heart.

"Yes. They run up just like the steps of a stair. Gerald's theoldest. He's twelve and they call him Jerry. He's a clever boy.Faith is eleven. She is a regular tomboy but pretty as apicture, I must say."

"She looks like an angel but she is a holy terror for mischief,Mrs. Dr. dear," said Susan solemnly. "I was at the manse onenight last week and Mrs. James Millison was there, too. She hadbrought them up a dozen eggs and a little pail of milk--a VERYlittle pail, Mrs. Dr. dear. Faith took them and whisked down thecellar with them. Near the bottom of the stairs she caught hertoe and fell the rest of the way, milk and eggs and all. You canimagine the re

are as much concerned as I; therefore, I propose that we should contrive measures and act in concert: communicate to me what you think the likeliest way to mortify her, while I, on my side, will inform you what my desire of revenge shall suggest to me." After this wicked agreement, the two sisters saw each other frequently, and consulted how they might disturb and interrupt the happiness of the queen. They proposed a great many ways, but in deliberating about the manner of executing them, found so many difficulties that they durst not attempt them. In the meantime, with a detestable dissimulation, they often went together to make her visits, and every time showed her all the marks of affection they could devise, to persuade her how overjoyed they were to have a sister raised to so high a fortune. The queen, on her part, constantly received them with all the demonstrations of esteem they could expect from so near a relative. Some time after her marriage, the expected birth of an heir gave great joy to the que

dently schoolrooms, for desks, maps, blackboards, and books were scattered about. An open fire burned on the hearth, and several indolent lads lay on their backs before it, discussing a new cricket-ground, with such animation that their boots waved in the air. A tall youth was practising on the flute in one corner, quite undisturbed by the racket all about him. Two or three others were jumping over the desks, pausing, now and then, to get their breath and laugh at the droll sketches of a little wag who was caricaturing the whole household on a blackboard.

In the room on the left a long supper-table was seen, set forth with great pitchers of new milk, piles of brown and white bread, and perfect stacks of the shiny gingerbread so dear to boyish souls. A flavor of toast was in the air, also suggestions of baked apples, very tantalizing to one hungry little nose and stomach.

The hall, however, presented the most inviting prospect of all, for a brisk game of tag was going on in the upper entry. One l

r, so that the little body presented a shapelessappearance, as, with its small feet shod in thick, nailedmountain-shoes, it slowly and laboriously plodded its way up inthe heat. The two must have left the valley a good hour's walkbehind them, when they came to the hamlet known as Dorfli, whichis situated half-way up the mountain. Here the wayfarers met withgreetings from all sides, some calling to them from windows, somefrom open doors, others from outside, for the elder girl was nowin her old home. She did not, however, pause in her walk torespond to her friends' welcoming cries and questions, but passedon without stopping for a moment until she reached the last ofthe scattered houses of the hamlet. Here a voice called to herfrom the door: "Wait a moment, Dete; if you are going up higher,I will come with you."

The girl thus addressed stood still, and the child immediatelylet go her hand and seated herself on the ground.

"Are you tired, Heidi?" asked her companion.

"No, I am hot," answe

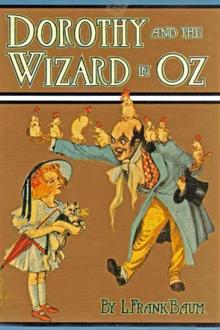

d at Zeb, whose face was blue and whose hair was pink, and gave a little laugh that sounded a bit nervous.

"Isn't it funny?" she said.

The boy was startled and his eyes were big. Dorothy had a green streak through the center of her face where the blue and yellow lights came together, and her appearance seemed to add to his fright.

"I--I don't s-s-see any-thing funny--'bout it!" he stammered.

[Illustration: HORSE, BUGGY AND ALL FELL SLOWLY.]

Just then the buggy tipped slowly over upon its side, the body of the horse tipping also. But they continued to fall, all together, and the boy and girl had no difficulty in remaining upon the seat, just as they were before. Then they turned bottom side up, and continued to roll slowly over until they were right side up again. During this time Jim struggled frantically, all his legs kicking the air; but on finding himself in his former position the horse said, in a relieved tone of voice:

"Well, that's better!"

Dorothy and Z

Another scholar would greet "the stranger," lead him around the room, and introduce him.

One day it was Abe's turn to do the introducing. He opened the door to find his best friend, Nat Grigsby, waiting outside. Nat bowed low, from the waist. Abe bowed. His buckskin trousers, already too short, slipped up still farther, showing several inches of his bare leg. He looked so solemn that some of the girls giggled. The schoolmaster frowned and pounded on his desk. The giggling stopped.

"Master Crawford," said Abe, "this here is Mr. Grigsby. His pa just moved to these parts. He figures on coming to your school."

Andrew Crawford rose and bowed. "Welcome," he said. "Mr. Lincoln, introduce Mr. Grigsby to the other scholars."

[Illustration]

The children sat on two long benches made of split logs. Abe led Nat down the length of the front bench. Each girl rose and made a curtsy. Nat bowed. Each boy rose and bowed. Nat returned the bow. Abe kept saying funny things under his breath that

"So much pettiness," he explained; "so much intrigue! And really, when one has an idea--a novel, fertilising idea--I don't want to be uncharitable, but--"

I am a man who believes in impulses. I made what was perhaps a rash proposition. But you must remember, that I had been alone, play-writing in Lympne, for fourteen days, and my compunction for his ruined walk still hung about me. "Why not," said I, "make this your new habit? In the place of the one I spoilt? At least, until we can settle about the bungalow. What you want is to turn over your work in your mind. That you have always done during your afternoon walk. Unfortunately that's over--you can't get things back as they were. But why not come and talk about your work to me; use me as a sort of wall against which you may throw your thoughts and catch t

t on the river?'

'Toad's out, for one,' replied the Otter. 'In his brand-new wager-boat; new togs, new everything!'

The two animals looked at each other and laughed.

'Once, it was nothing but sailing,' said the Rat, 'Then he tired of that and took to punting. Nothing would please him but to punt all day and every day, and a nice mess he made of it. Last year it was house-boating, and we all had to go and stay with him in his house-boat, and pretend we liked it. He was going to spend the rest of his life in a house-boat. It's all the same, whatever he takes up; he gets tired of it, and starts on something fresh.'

'Such a good fellow, too,' remarked the Otter reflectively: 'But no stability--especially in a boat!'

From where they sat they could get a glimpse of the main stream across the island that separated them; and just then a wager-boat flashed into view, the rower--a short, stout figure--splashing badly and rolling a good deal, but working his hardest. The Rat stood up a