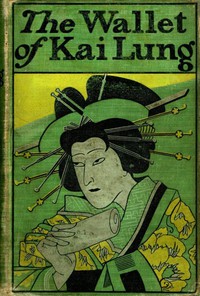

The Wallet of Kai Lung by Ernest Bramah (books successful people read .TXT) 📖

- Author: Ernest Bramah

Book online «The Wallet of Kai Lung by Ernest Bramah (books successful people read .TXT) 📖». Author Ernest Bramah

In the morning Yin’s spirit came back to the earth amid the sound of music of a celestial origin, which ceased immediately he recovered full consciousness. Accepting this manifestation as an omen of Divine favour, Yin journeyed towards the centre of the island where the rock stood, at every step passing the bones of innumerable ones who had come on a similar quest to his, and perished. Many of these had left behind them inscriptions on wood or bone testifying their deliberate opinion of the sacred rock, the island, their protecting deities, and the entire train of circumstances, which had resulted in their being in such a condition. These were for the most part of a maledictory and unencouraging nature, so that after reading a few, Yin endeavoured to pass without being in any degree influenced by such ill-judged outbursts.

“Accursed be the ancestors of this tormented one to four generations back!” was prominently traced upon an unusually large shoulder-blade. “May they at this moment be simmering in a vat of unrefined dragon’s blood, as a reward for having so undiscriminatingly reared the person who inscribes these words only to attain this end!” “Be warned, O later one, by the signs around!” Another and more practical-minded person had written: “Retreat with all haste to your vessel, and escape while there is yet time. Should you, by chance, again reach land through this warning, do not neglect, out of an emotion of gratitude, to burn an appropriate amount of sacrifice paper for the lessening of the torments of the spirit of Li-Kao,” to which an unscrupulous one, who was plainly desirous of sharing in the benefit of the requested sacrifice, without suffering the exertion of inscribing a warning after the amiable manner of Li-Kao, had added the words, “and that of Huan Sin.”

Halting at a convenient distance from one side of the rock which, without being carved by any person’s hand, naturally resembled the symmetrical countenance of a recumbent dragon (which he therefore conjectured to be the chief point of the entire mass), Yin built his fire and began an unremitting course of sacrifice and respectful ceremony. This manner of conduct he observed conscientiously for the space of seven days. Towards the end of that period a feeling of unendurable dejection began to possess him, for his stores of all kinds were beginning to fail, and he could not entirely put behind him the memory of the various well-intentioned warnings which he had received, or the sight of the fleshless ones who had lined his path. On the eighth day, being weak with hunger and, by reason of an intolerable thirst, unable to restrain his body any longer in the spot where he had hitherto continuously prostrated himself nine-and-ninety times each hour without ceasing, he rose to his feet and retraced his steps to the boat in order that he might fill his water-skins and procure a further supply of food.

With a complicated emotion, in which was present every abandoned and disagreeable thought to which a person becomes a prey in moments of exceptional mental and bodily anguish, he perceived as soon as he reached the edge of the water that the boat, upon which he was confidently relying to carry him back when all else failed, had disappeared as entirely as the smoke from an extinguished opium pipe. At this sight Yin clearly understood the meaning of Li-Kao’s unregarded warning, and recognized that nothing could now save him from adding his incorruptible parts to those of the unfortunate ones whose unhappy fate had, seven days ago, engaged his refined pity. Unaccountably strengthened in body by the indignation which possessed him, and inspired with a virtuous repulsion at the treacherous manner of behaving on the part of those who guided his destinies, he hastened back to his place of obeisance, and perceiving that the habitually placid and introspective expression on the dragon face had imperceptibly changed into one of offensive cunning and unconcealed contempt, he snatched up his spear and, without the consideration of a moment, hurled it at a score of paces distance full into the sacred but nevertheless very unprepossessing face before him.

At the instant when the presumptuous weapon touched the holy stone the entire intervening space between the earth and the sky was filled with innumerable flashes of forked and many-tongued lightning, so that the island had the appearance of being the scene of a very extensive but somewhat badly-arranged display of costly fireworks. At the same time the thunder rolled among the clouds and beneath the sea in an exceedingly disconcerting manner. At the first indication of these celestial movements a sudden blindness came upon Yin, and all power of thought or movement forsook him; nevertheless, he experienced an emotion of flight through the air, as though borne upwards upon the back of a winged creature. When this emotion ceased, the blindness went from him as suddenly and entirely as if a cloth had been pulled away from his eyes, and he perceived that he was held in the midst of a boundless space, with no other object in view than the sacred rock, which had opened, as it were, revealing a mighty throng within, at the sight of whom Yin’s internal organs trembled as they would never have moved at ordinary danger, for it was put into his spirit that these in whose presence he stood were the sacred Emperors of his country from the earliest time until the usurpation of the Chinese throne by the devouring Tartar hordes from the North.

As Yin gazed in fear-stricken amazement, a knowledge of the various Pure Ones who composed the assembly came upon him. He understood that the three unclad and commanding figures which stood together were the Emperors of the Heaven, Earth, and Man, whose reigns covered a space of more than eighty thousand years, commencing from the time when the world began its span of existence. Next to them stood one wearing a robe of leopard-skin, his hand resting upon a staff of a massive club, while on his face the expression of tranquillity which marked his predecessors had changed into one of alert wakefulness; it was the Emperor of Houses, whose reign marked the opening of the never-ending strife between man and all other creatures. By his side stood his successor, the Emperor of Fire, holding in his right hand the emblem of the knotted cord, by which he taught man to cultivate his mental faculties, while from his mouth issued smoke and flame, signifying that by the introduction of fire he had raised his subjects to a state of civilized life.

On the other side of the boundless chamber which seemed to be contained within the rocks were Fou-Hy, Tchang-Ki, Tcheng-Nung, and Huang, standing or reclining together. The first of these framed the calendar, organized property, thought out the eight Essential Diagrams, encouraged the various branches of hunting, and the rearing of domestic animals, and instituted marriage. From his couch floated melodious sounds in remembrance of his discovery of the property of stringed woods. Tchang-Ki, who manifested the property of herbs and growing plants, wore a robe signifying his attainments by means of embroidered symbols. His hand rested on the head of the dragon, while at his feet flowed a bottomless canal of the purest water. The discovery of written letters by Tcheng-Nung, and his ingenious plan of grouping them after the manner of the constellations of stars, was emblemized in a similar manner, while Huang, or the Yellow Emperor, was surrounded by ores of the useful and precious metals, weapons of warfare, written books, silks and articles of attire, coined money, and a variety of objects, all testifying to his ingenuity and inspired energy.

These illustrious ones, being the greatest, were the first to take Yin’s attention, but beyond them he beheld an innumerable concourse of Emperors who not infrequently outshone their majestic predecessors in the richness of their apparel and the magnificence of the jewels which they wore. There Yin perceived Hung-Hoang, who first caused the chants to be collected, and other rulers of the Tcheon dynasty; Yong-Tching, who compiled the Holy Edict; Thang rulers whose line is rightly called “the golden,” from the unsurpassed excellence of the composed verses which it produced; renowned Emperors of the versatile Han dynasty; and, standing apart, and shunned by all, the malignant and narrow-minded Tsing-Su-Hoang, who caused the Sacred Books to be burned.

Even while Yin looked and wondered, in great fear, a rolling voice, coming from one who sat in the midst of all, holding in his right hand the sun, and in his left the moon, sounded forth, like the music of many brass instruments playing in unison. It was the First Man who spoke.

“Yin, son of Yat Huang, and creature of the Lower Part,” he said, “listen well to the words I speak, for brief is the span of your tarrying in the Upper Air, nor will the utterance I now give forth ever come unto your ears again, either on the earth, or when, blindly groping in the Middle Distance, your spirit takes its nightly flight. They who are gathered around, and whose voices I speak, bid me say this: Although immeasurably above you in all matters, both of knowledge and of power, yet we greet you as one who is well-intentioned, and inspired with honourable ambition. Had you been content to entreat and despair, as did all the feeble and incapable ones whose white bones formed your pathway, your ultimate fate would have in no wise differed from theirs. But inasmuch as you held yourself valiantly, and, being taken, raised an instinctive hand in return, you have been chosen; for the day to mute submission has, for the time or for ever, passed away, and the hour is when China shall be saved, not by supplication, but by the spear.”

“A state of things which would have been highly unnecessary if I had been permitted to carry out my intention fully, and restore man to his prehistoric simplicity,” interrupted Tsin-Su-Hoang. “For that reason, when the voice of the assemblage expresses itself, it must be understood that it represents in no measure the views of Tsin-Su-Hoang.”

“In the matter of what has gone before, and that which will follow hereafter,” continued the Voice dispassionately, “Yin, the son of Yat-Huang, must concede that it is in no part the utterance of Tsin-Su-Hoang—Tsin-Su-Hoang who burned the Sacred Books.”

At the mention of the name and offence of this degraded being a great sound went up from the entire multitude—a universal cry of execration, not greatly dissimilar from that which may be frequently heard in the crowded Temple of Impartiality when the one whose duty it is to take up, at a venture, the folded papers, announces that the sublime Emperor, or some mandarin of exalted rank, has been so fortunate as to hold the winning number in the Annual State Lottery. So vengeance-laden and mournful was the combined and evidently preconcerted wail, that Yin was compelled to shield his ears against it; yet the inconsiderable Tsin-Su-Hoang, on whose account it was raised, seemed in no degree to be affected by it, he, doubtless, having become hardened by hearing a similar outburst, at fixed hours, throughout interminable cycles of time.

When the last echo

Comments (0)