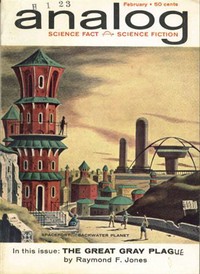

The Great Gray Plague by Raymond F. Jones (moboreader .txt) 📖

- Author: Raymond F. Jones

Book online «The Great Gray Plague by Raymond F. Jones (moboreader .txt) 📖». Author Raymond F. Jones

Baker smiled grimly as Wily stormed out. Then he picked up the phone and asked Doris to get Fenwick at Clearwater. When Fenwick finally came on, Baker said, "Wily was just here. I expected he would be the one. This is going to be it. Send me everything you've got for release. We're going to find out how right Sam Atkins was!"

He called the other maverick schools he'd given grants, and the penny ante commercial organizations he'd set on their feet. He gave them the same message.

It wasn't going to be easy or pleasant, he reflected. The biggest guns of Scientific Authority would be trained on him before this was over.

Drew Pearson had the word even before it reached Baker. Baker read it at breakfast a week after Wily's visit. The columnist said, "The next big spending agency to come under the fire of Congressional Investigation is none other than the high-echelon National Bureau of Scientific Development. Dr. William Baker, head of the Agency, has been accused of indiscriminate spending policies wholly unrelated to the national interest. The accusers are a group of elite universities and top manufacturing organizations that have benefited greatly from Baker's handouts in years past. This year, Baker is accused of giving upwards of five million dollars to crackpot groups and individuals who have no standing in the scientific community whatever.

"If these charges are true, it is difficult to see what Dr. Baker is up to. For many years he has had an enviable record as a tight-fisted, hard-headed administrator of these important funds. Congress intends to find out what's going on. The watchdog committee of Senator Landrus is expected to call an investigation early next week."

Baker was notified that same afternoon.

Senator Landrus was a big, florid man, who moved about a committee hearing chamber with the ponderous smoothness of a luxury liner. He was never visited by a single doubt about the rightness of his chosen course—no matter how erratic it might appear to an onlooker. His faith in his established legislative procedures and in the established tenets of Science was complete. Since he wore the shield of both camps, his confidence in the path of Senator Robert Landrus was also unmarred by questions.

Baker had faced him many times, but always as an ally. Now, recognizing him as the enemy, Baker felt some small qualms, not because he feared Landrus, but because so much was at stake in this hearing. So much depended on his ability to guide the whims and uncertainties of this mammoth vessel of Authority.

There was an unusual amount of press interest in what might have seemed a routine and unspectacular hearing. No one could recall a previous occasion when the recipients had challenged a Government handout agency regarding the size of the handouts. While Landrus made his opening statement several of the reporters fiddled with the idea of a headline that said something about biting the hand that feeds. It wouldn't quite come off.

Wily was invited to make his statement next, which he did with icy reserve, never once looking in Baker's direction. He was followed by two other university presidents and a string of laboratory directors. The essence of their remarks was that Russia was going to beat the pants off American researchers, and it was all Baker's fault.

This recital took up all of the morning and half the afternoon of the first day. A dozen or so corporation executives were next on the docket with complaints that their vast facilities were being hamstrung by Baker's sudden switch of R & D funds to less qualified agents. Baker observed that the ones complaining were some of those who had never spent a nickel on genuine research until the Government began buying it. He knew that Landrus had not observed this fact. It would have to be called to the senator's attention.

By the end of the day, Landrus looked grave. It was obvious that he could see nothing but villainy in Baker's recent performance. It had been explained to him in careful detail by some of the most powerful men in the nation. Baker was certainly guilty of criminal negligence, if not more, in derailing these funds which Congress had intended should go to the support of the nation's scientific leaders. Landrus felt a weary depression. He hadn't really believed it would turn out this bad for Baker, for whom he had had a considerable regard in times past.

"You have heard the testimony of these witnesses," Landrus said to Baker. "Do you wish to reply or make a statement of your own, Dr. Baker?"

"I most certainly do!" said Baker.

Landrus didn't see what was left for Baker to say. "Testimony will resume tomorrow at nine a.m.," he said. "Dr. Baker will present his statement at that time."

The press thought it looked bad for Baker, too. Some papers accused him openly of attempting to sabotage the nation's research program. Wily and his fellows, and Landrus, were commended for catching this defection before it progressed any further.

Baker was well aware he was in a tight spot, and one which he had deliberately created. But as far as he could see, it was the only chance of utilizing the gift that Sam Atkins had left him. He felt confident he had a fighting chance.

His battery of supporters had not even been noticed in the glare of Wily's brilliant assembly, but Fenwick was there, and Ellerbee. Fenwick's fair-haired boy, George, and a half dozen of his new recruits were there. Also present were the heads of the other maverick schools like Clearwater, and the presidents—some of whom doubled as janitors—of the minor corporations Baker had sponsored.

Baker took the stand the following morning, armed with his charts and displays. He looked completely confident as he addressed Landrus and the assembly.

"Gentlemen—and ladies—" he said. "The corner grocery store was one of America's most familiar and best loved institutions a generation or two ago. In spite of this, it went out of business because we refused to support it. May I ask why we refused to continue to support the corner grocery?

"The answer is obvious. We began to find better bargains elsewhere, in the supermarket. As much as we regret the passing of the oldtime grocer I'm sure that none of us would seriously suggest we bring him back.

"For the same reason I suggest that the time may have come to reconsider the bargains we have been getting in scientific developments and inventions. Americans have always taken pride in driving a good, hard, fair bargain. I see no reason why we should not do the same when we go into the open market to buy ideas.

"Some months ago I began giving fresh consideration to the product we were buying with the millions of dollars in grants made by NBSD. It was obvious that we were buying an impressive collection of shiny, glass and metal laboratories. We were buying giant pieces of laboratory equipment and monstrous machines of other kinds. We were getting endless quantities of fat reports—they fill thousands of miles of microfilm.

"Then I discovered an old picture of what I am sure all unbiased scientists will recognize as the world's greatest laboratory—greatest in terms of measurable output. I brought this picture with me."

Baker unrolled the first of his exhibits, a large photographic blowup. The single, whitehaired figure seated at a desk was instantly recognized. Wily and his group glanced at the picture and glared at Baker.

"You recognize Dr. Einstein, of course," said Baker. "This is a photograph of him at work in his laboratory at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton."

"We are all familiar with the appearance of the great Dr. Einstein," said Landrus. "But you are not showing us anything of his laboratory, as you claimed."

"Ah, but I am!" said Baker. "This is all the laboratory Dr. Einstein ever had. A desk, a chair, some writing paper. You will note that even the bookshelves behind him are bare except for a can of tobacco. The greatest laboratory in the world, a place for a man's mind to work in peace. Nuclear science began here."

Wily jumped to his feet. "This is absurd! No one denies the greatness of Dr. Einstein's work, but where would he have been without billions of dollars spent at Oak Ridge, Hanford, Los Alamos, and other great laboratories. To say that Dr. Einstein did not use laboratory facilities does not imply that vast expenditures for laboratories are not necessary!"

"I should like to reverse your question, Dr. Wily, and then let it rest," said Baker. "What would Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Los Alamos have done without Dr. Einstein?"

Senator Landrus floated up from his chair and raised his hands. "Let us be orderly, gentlemen. Dr. Baker has the floor. I should not like to have him interrupted again, please."

Baker nodded his thanks to the senator. "It has been charged," Baker continued, "that the methods of NBSD in granting funds for research have changed in recent times. This is entirely correct, and I should first like to show the results of this change."

He unrolled a chart and pinned it to the board behind him. "This chart shows what we have been paying and what we have been getting. The black line on the upper half of the chart shows the number of millions of dollars spent during the past five years. Our budget has had a moderately steady rise. The green line shows the value of laboratories constructed and equipment purchased. The red line shows the measure of new concepts developed by the scientists in these laboratories, the improvement on old concepts, and the invention of devices that are fundamentally new in purpose or function."

The gallery leaned forward to stare at the chart. From press row came the popping of flash cameras. Then a surge of spontaneous comment rolled through the chamber as the audience observed the sharp rise of the red line during the last six months, and the dropping of the green line.

Wily was on his feet again. "An imbecile should be able to see that the trend of the red line is the direct result of the previous satisfactory expenditures for facilities. One follows the other!"

Landrus banged for order.

"That's a very interesting point," said Baker. "I have another chart here"—he unrolled and pinned it—"that shows the output in terms of concepts and inventions, plotted against the size of the grants given to the institution."

The curve went almost straight downhill.

Wily was screaming. "Such data are absolutely meaningless! Who can say what constitutes a new idea, a new invention? The months of groundwork—"

"It will be necessary to remove any further demonstrators from the hearing room," said Landrus. "This will be an orderly hearing if I have to evict everyone but Dr. Baker and myself. Please continue, doctor."

"I am quite willing for my figures and premises to be examined in all detail," said Baker. "I will be glad to supply the necessary information to anyone who desires it at the close of this session. In the meantime, I should like to present a picture of the means which we have devised to determine whether a grant should be made to any given applicant.

"I am sure you will agree, Senator Landrus and Committee members, that it would be criminal to make such choices on any but the most scientific basis. For this reason, we have chosen to eliminate all elements of bias, chance, or outright error. We have developed a highly advanced scientific tool which we know simply as The Index."

Baker posted another long chart on the wall, speaking as he went. "This chart represents the index of an institution which shall remain anonymous as Sample A. However, I would direct Dr. Wily's close attention to this exhibit. The black median line indicates the boundary of characteristics which have been determined as acceptable or nonacceptable for grants. The colored areas on either side of the median line show strength of the various factors represented in any one institution. The Index is very simple. All that is required is that fifty per cent of the area above the line be colored in order to be eligible for a grant. You will note that in the case of Sample A the requirement is not met."

Fenwick couldn't believe his eyes. The chart was almost like the first one he had ever seen, the one prepared for Clearwater College months ago. He hadn't even known that Baker was still using the idiotic Index. Something was wrong, he told himself—all wrong.

"The Index is a composite," Baker was saying; "the final resultant of many individual charts, and it is the individual charts that will show you the factors which are measured. These factors are determined by an analysis of information supplied directly by the institution.

"The first of these factors is admissions. For a college, it is admission as a

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)