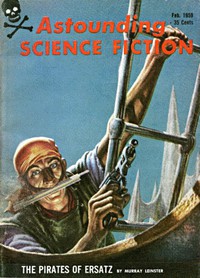

The Pirates of Ersatz by Murray Leinster (best business books of all time TXT) 📖

- Author: Murray Leinster

Book online «The Pirates of Ersatz by Murray Leinster (best business books of all time TXT) 📖». Author Murray Leinster

"This is a very bad business, my dear fellow," he said benevolently. "Has Fani told you of the people who arrived from Walden in search of you? They tell me terrible things about you!"

"Yes," said Hoddan. He prepared a roll for biting. He said: "One of them, I think, is named Derec. He's to identify me so good money isn't wasted paying for the wrong man. The other man's police, isn't he?" He reflected a moment. "If I were you, I'd start talking at a million credits. You might get half that."

He bit into the roll as Don Loris looked shocked.

"Do you think," he asked indignantly, "that I would give up the rescuer of my daughter to emissaries from a foreign planet, to be locked in a dungeon for life?"

"Not in those words," conceded Hoddan. "But after all, despite your deep gratitude to me, there are such things as one's duty to humanity as a whole. And while it would cause you bitter anguish if someone dear to you represented a danger to millions of innocent women and children—still, under such circumstances you might feel it necessary to do violence to your own emotions."

Don Loris looked at him with abrupt suspicion. Hoddan waved the roll.

"Moreover," he observed, "gratitude for actions done on Darth does not entitle you to judge of my actions on Walden. While you might and even should feel obliged to defend me in all things I have done on Darth, your obligation to me does not let you deny that I may have acted less defensibly on Walden."

Don Loris looked extremely uneasy.

"I may have thought something like that," he admitted. "But—"

"So that," said Hoddan, "while your debt to me cannot and should not be overlooked, nevertheless"—Hoddan put the roll into his mouth and spoke less clearly—"you feel that you should give consideration to the claims of Walden to inquire into my actions while there."

He chewed, and swallowed, and said gravely:

"And can I make deathrays?"

Don Loris brightened. He drew a deep breath of relief. He said complainingly:

"I don't see why you're so sarcastic! Yes. That is a rather important question. You see, on Walden they don't know how to. They say you do. They're very anxious that nobody should be able to. But while in unscrupulous hands such an instrument of destruction would be most unfortunate ... ah ... under proper control—"

"Yours," said Hoddan.

"Say—ours," said Don Loris hopefully. "With my experience of men and affairs, and my loyal and devoted retainers—"

"And cozy dungeons," said Hoddan. He wiped his mouth. "No."

Don Loris started violently.

"No, what?"

"No deathrays," said Hoddan. "I can't make 'em. Nobody can. If they could be made, some star somewhere would be turning them out, or some natural phenomenon would let them loose from time to time. If there were such things as deathrays, all living things would have died, or else would have adjusted to their weaker manifestations and developed immunity so they wouldn't be deathrays any longer. As a matter of fact, that's probably been the case, some time in the past. So far as the gadget goes that they're talking about, it's been in use for half a century in the Cetis cluster. Nobody's died of it yet."

Don Loris looked bitterly disappointed.

"That's the truth?" he asked unhappily. "Honestly? That's your last word on it?"

"Much," said Hoddan, "much as I hate to spoil the prospects of profitable skulduggery, that's my last word and it's true."

"But those men from Walden are very anxious!" protested Don Loris. "There was no ship available, so their government got a liner that normally wouldn't stop here to take an extra lifeboat aboard. It came out of overdrive in this solar system, let out the lifeboat, and went on its way again. Those two men are extremely anxious—"

"Ambitious, maybe," said Hoddan. "They're prepared to pay to overcome your sense of gratitude to me. Naturally, you want all the traffic will bear. I think you can get half a million."

Don Loris looked suspicious again.

"You don't seem worried," he said fretfully. "I don't understand you!"

"I have a secret," said Hoddan.

"What is it?"

"It will develop," said Hoddan.

Don Loris hesitated, essayed to speak, and thought better of it. He shrugged his shoulders and went slowly back to the flight of stone steps. He descended. The Lady Fani started to wring her hands. Then she said hopefully:

"What's your secret?"

"That your father thinks I have one," said Hoddan. "Thanks for the breakfast. Should I walk out the gate, or—"

"It's closed," said the Lady Fani forlornly. "But I have a rope for you. You can go down over the wall."

"Thanks," said Hoddan. "It's been a pleasure to rescue you."

"Will you—" Fani hesitated. "I've never known anybody like you before. Will you ever come back?"

Hoddan shook his head at her.

"Once you asked me if I'd fight for you, and look what it got me into! No commitments."

He glanced along the battlements. There was a fairly large coil of rope in view. He picked up his bag and went over to it. He checked the fastening of one end and tumbled the other over the wall.

Ten minutes later he trudged up to Thal, waiting in the nearby woodland with two horses.

"The Lady Fani," he said, "has the kind of brains I like. She pulled up the rope again."

Thal did not comment. He watched morosely as Hoddan made the perpetually present ship bag fast to his saddle and then distastefully climbed aboard the horse.

"What are you going to do?" asked Thal unhappily. "I didn't make a parting-present to Don Loris, so I'll be disgraced if he finds out I helped you. And I don't know where to take you."

"Where," asked Hoddan, "did those characters from Walden come down?"

Thal told him. At the castle of a considerable feudal chieftain, on the plain some four miles from the mountain range and six miles this side of the spaceport.

"We ride there," said Hoddan. "Liberty is said to be sweet, but the man who said that didn't have blisters from a saddle. Let's go."

They rode away. There would be no immediate pursuit, and possibly none at all. Don Loris had left Hoddan at breakfast on the battlements. The Lady Fani would make as much confusion over his disappearance as she could. But there'd be no search for him until Don Loris had made his deal.

Hoddan was sure that Fani's father would have an enjoyable morning. He would relish the bargaining session. He'd explain in great detail how valuable had been Hoddan's service to him, in rescuing Fani from an abductor who would have been an intolerable son-in-law. He'd grow almost tearful as he described his affection for Hoddan—how he loved his daughter—as he observed grievedly that they were asking him to betray the man who had saved for him the solace of his old age. He would mention also that the price they offered was an affront to his paternal affection and his dignity as prince of this, baron of that, lord of the other thing and claimant to the dukedom of something-or-other. Either they'd come up or the deal was off!

But meanwhile Hoddan and Thal rode industriously toward the place from which those emissaries had come.

All was tranquil. All was calm. Once they saw a dust cloud, and Thal turned aside to a providential wooded copse, in which they remained while a cavalcade went by. Thal explained that it was a feudal chieftain on his way to the spaceport town. It was simple discretion for them not to be observed, said Thal, because they had great reputations as fighting men. Whoever defeated them would become prominent at once. So somebody might try to pick a quarrel under one of the finer points of etiquette when it would be disgrace to use anything but standard Darthian implements for massacre. Hoddan admitted that he did not feel quarrelsome.

They rode on after a time, and in late afternoon the towers and battlements of the castle they sought appeared. The ground here was only gently rolling. They approached it with caution, following the reverse slope of hills, and dry stream-beds, and at last penetrating horse-high brush to the point where they could see it clearly.

If Hoddan had been a student of early terrestrial history, he might have remarked upon the re-emergence of ancient architectural forms to match the revival of primitive social systems. As it was, he noted in this feudal castle the use of bastions for flanking fire upon attackers, he recognized the value of battlements for the protection of defenders while allowing them to shoot, and the tricky positioning of sally ports. He even grasped the reason for the massive, stark, unornamented keep. But his eyes did not stay on the castle for long. He saw the spaceboat in which Derec and his more authoritative companion had arrived.

It lay on the ground a half mile from the castle walls. It was a clumsy, obese, flattened shape some forty feet long and nearly fifteen wide. The ground about it was scorched where it had descended upon its rocket flames. There were several horses tethered near it, and men who were plainly retainers of the nearby castle reposed in its shade.

Hoddan reined in.

"Here we part," he told Thal. "When we first met I enabled you to pick the pockets of a good many of your fellow-countrymen. I never asked for my split of the take. I expect you to remember me with affection."

Thal clasped both of Hoddan's hands in his.

"If you ever return," he said with mournful warmth, "I am your friend!"

Hoddan nodded and rode out of the brushwood toward the spaceboat—the lifeboat—that had landed the emissaries from Walden. That it landed so close to the spaceport, of course, was no accident. It was known on Walden that Hoddan had taken space passage to Darth. He'd have landed only two days before his pursuers could reach the planet. And on a roadless, primitive world like Darth he couldn't have gotten far from the spaceport. So his pursuers would have landed close by, also. But it must have taken considerable courage. When the landing grid failed to answer, it must have seemed likely that Hoddan's deathrays had been at work.

Here and now, though, there was no uneasiness. Hoddan rode heavily, without haste, through the slanting sunshine. He was seen from a distance and watched without apprehension by the loafing guards about the boat. He looked hot and thirsty. He was both. So the posted guard merely looked at him without too much interest when he brought his dusty mount up to the shadow the lifeboat cast, and apparently decided that there wasn't room to get into it.

He grunted a greeting and looked at them speculatively.

"Those two characters from Walden," he observed, "sent me to get something from this thing, here. Don Loris told 'em I was a very honest man."

He painstakingly looked like a very honest man. After a moment there were responsive grins.

"If there's anything missing when I start back," said Hoddan, "I can't imagine how it happened! None of you would take anything. Oh, no! I bet you'll blame it on me!" He shook his head and said "Tsk. Tsk. Tsk."

One of the guards sat up and said appreciatively:

"But it's locked. Good."

"Being an honest man," said Hoddan amiably, "they told me how to unlock it."

He got off his horse. He removed the bag from his saddle. He went into the grateful shadow of the metal hull. He paused and mopped his face and then went to the entrance port. He put his hand on the turning bar. Then he painstakingly pushed in the locking-stud with his other hand. Of course the handle turned. The boat port opened. The two from Walden would have thought everything safe because it was under guard. On Walden that protection would have been enough. On Darth, the spaceboat had not been looted simply because locks, there, were not made with separate vibration-checks to keep vibration from loosening them. On spaceboats such a precaution was usual.

"Give me two minutes," said Hoddan over his shoulder. "I have to get what they sent me for. After that everybody starts even."

He entered and closed the door behind him. Then he locked it. By the nature of things it is as needful to be able to lock a spaceboat from the inside as it is unnecessary to lock it from without.

He looked things over. Standard equipment everywhere. He checked everything, even to the fuel supply. There were knockings on the port. He continued to inspect. He turned on the visionscreens, which provided the control room—indeed, all the boat—with an unobstructed view in all directions. He was satisfied.

The knocks became bangings. Something approaching indignation could be deduced. The guards around the spaceboat felt that Hoddan was taking an unfair amount of time

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)