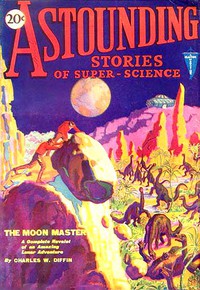

Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 by Various (red queen ebook TXT) 📖

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 by Various (red queen ebook TXT) 📖». Author Various

In the mind of Sarka the Second there still loomed a hellish doubt that would not down.

The men of Cleric were surrounding Jaska now, protecting her with their lives against the tentacles of that lone Aircar splashed with crimson—and all were flying a losing race with the Earth, which was still being forced outward from the Moon!

An Exciting Interplanetary Story

By R. F. Starzl EARTH, THE MARAUDERPart Two of the Thrilling Novel

By Arthur J. Burks THE FLYING CITYA Novelet Concerning an Amazing Aerial Metropolis

By H. Thompson Rich MURDER MADNESSThe Conclusion of the Gripping Continued Novel

By Murray Leinster——And Others!

[Pg 48]

From An Amber Block By Tom Curry Marable, in a desperate frenzy, hacked at the reptile's awful head.

Marable, in a desperate frenzy, hacked at the reptile's awful head.

"

These should prove especially valuable and interesting without a doubt, Marable," said the tall, slightly stooped man. He waved a long hand toward the masses of yellow brown which filled the floor of the spacious workrooms, towering almost to the skylights, high above their heads.

"Is that coal in the biggest one with the dark center?" asked an attractive young woman who stood beside the elder of the men.

"I am inclined to believe it will prove to be some sort of black liquid," said Marable, a big man of thirty-five.

There were other people about the immense rooms, the laboratories of the famous Museum of Natural History. Light streamed in from the skylights and windows; fossils of all kinds, some immense in size, were distributed about. Skilled specialists were chipping away at matrices other artists were reconstructing, doing a thousand things necessary to the work.

A hum of low talking, accompanied by the irregular tapping of chisels on stone, came to their ears, though they took no heed of this, since they worked here day after day, and it was but the usual sound of the paleontologists' laboratory.

Marable threw back his blond head. He glanced again toward the dark haired, blue eyed young woman, but when he caught her eye, he looked away and spoke to her father, Professor Young.

"I think that big one will turn out to be the largest single piece of amber ever mined," he said. "There were many difficulties in getting it out, for the workmen seemed afraid of it, did not want to handle it for some silly reason or other."

Professor Young, curator, was an expert in his line, but young Marable had charge of these particular fossil blocks, the amber being pure because it was mixed with lignite. The particular block which held the interest of the three was a huge yellow brown mass of irregular shape. Vaguely, through the outer shell of impure amber, could be seen the heart of ink. The chunk weighed many tons, and its crate had just been removed by some workmen and was being taken away, piece by piece.

The three gazed at the immense mass, which filled the greater part of one end of the laboratory and towered almost to the skylights. It was a small mountain, compared to the size of the room, and in this case the mountain had come to man.

"Miss Betty, I think we had better begin by drawing a rough sketch of the block," said Marable.

Betty Young, daughter of the curator, nodded. She was working as assistant and secretary to Marable.

"Well—what do you think of them?"

The voice behind them caused them to turn, and they looked into the face of Andrew Leffler, the millionaire paleontologist, whose wealth and interest in the museum had made it possible for the institution to acquire the amber.[Pg 49]

Leffler, a keen, quick moving little man, whose chin was decorated with a white Van Dyke beard, was very proud of the new acquisition.

"Everybody is talking about the big one," he continued, putting his hand on Marable's shoulder. "Orling is coming to see, and many others. As I told you, the workmen who handled it feared the big one. There were rumors about some unknown devil which lay hidden in the inklike substance, caught there like the proverbial fly in the amber. Well, let us hope there is something good in there, something that will make worth while all our effort."

Leffler wandered away, to speak to others who inspected the amber blocks.

"Superstition is curious, isn't it?" said Marable. "How can anyone think that a fossil creature, penned in such a cell for thousands and thousands of years, could do any harm?"

Professor Young shrugged. "It is just as you say. Superstition is not reasonable. These amber blocks were mined in the Manchurian lignite deposits by Chinese coolies under Japanese masters. They believe anything, the coolies. I remember working once with a crew of them that thought—"

The professor stopped suddenly, for his daughter had uttered a little cry of alarm. He felt her hand upon his arm, and turned toward her.

"What is it, dear?" he asked.

She was pointing toward the biggest amber block, and her eyes were wide open and showed she had seen something, or imagined that she had seen something, that frightened her.

Professor Young followed the direction of her finger. He saw that she was staring at the black heart of the amber block; but when he looked he could see nothing but the vague, irregular outline of the inky substance.

"What is it, dear?" asked Young again.

"I—I thought I saw it looking out, eyes that stared at us—"

The girl broke off, laughed shortly, and added, "I suppose it was Mr. Leffler's talking. There's nothing there now."

"Probably the Manchurian devil shows itself only to you," said her father jokingly. "Well, be careful, dear. If it takes a notion to jump out at you, call me and I'll exorcise it for you."

Betty blushed and laughed again. She looked at Marable, expecting to see a smile of derision on the young man's face, but his expression was grave.

The light from above was diminishing; outside sounded the roar of home-going traffic.

"Well, we must go home," said Professor Young. "There's a hard and interesting day ahead of us to-morrow, and I want to read Orling's new work on matrices before we begin chipping at the amber."

Young turned on his heel and strode toward the locker at the end of the room where he kept his coat and hat. Betty, about to follow him, was aware of a hand on her arm, and she turned to find Marable staring at her.

"I saw them, too," he whispered. "Could it have been just imagination? Was it some refraction of the light?"

The girl paled. "I—I don't know," she replied, in a low voice. "I thought I saw two terrible eyes glaring at me from the inky heart. But when father laughed at me, I was ashamed of myself and thought it was just my fancy."

"The center is liquid, I'm sure," said Marable. "We will find that out soon enough, when we get started."

"Anyway, you must be careful, and so must father," declared the girl.

She looked at the block again, as it towered there above them, as though she expected it to open and the monster of the coolies' imagination leap out.

"Come along, Betty," called her father.[Pg 50]

She realized then that Marable was holding her hand. She pulled away and went to join her father.

It was slow work, chipping away the matrix. Only a bit at a time could be cut into, for they came upon many insects imbedded in the amber. These small creatures proved intensely interesting to the paleontologists, for some were new to science and had to be carefully preserved for study later on.

Marable and her father labored all day. Betty, aiding them, was obviously nervous. She kept begging her father to take care, and finally, when he stopped work and asked her what ailed her, she could not tell him.

"Be careful," she said, again and again.

Her father realized that she was afraid of the amber block, and he poked fun at her ceaselessly. Marable said nothing.

"It's getting much softer, now the outside shell is pierced," said Young, late in the day.

"Yes," said Marable, pausing in his work of chipping away a portion of matrix. "Soon we will strike the heart, and then we will find out whether we are right about it being liquid. We must make some preparations for catching it, if it proves to be so."

The light was fading. Outside, it was cold, but the laboratories were well heated by steam. Close by where they worked was a radiator, so that they had been kept warm all day.

Most of the workers in the room were making ready to leave. Young and Marable, loath to leave such interesting material, put down their chisels last of all. Throughout the day various scientific visitors had interrupted them to inspect the immense amber block, and hear the history of it.

All day, Betty Young had stared fascinatedly at the inky center.

"I think it must have been imagination," she whispered to Marable, when Young had gone to don his coat and hat. "I saw nothing to-day."

"Nor did I," confessed Marable. "But I thought I heard dull scrapings inside the block. My brain tells me I'm an imaginative fool, that nothing could be alive inside there, but just the same, I keep thinking about those eyes we thought we saw. It shows how far the imagination will take one."

"It's getting dark, Betty," said her father. "Better not stay here in the shadows or the devil will get you. I wonder if it will be Chinese or up-to-date American!"

The girl laughed, said good night to Marable, and followed her father from the laboratory. As they crossed the threshold a stout, red-faced man in a gray uniform, a watchman's clock hanging at his side, raised his hat and smiled at the young woman and her father.

"Hello, Rooney," cried Betty.

"How d'ye do, Miss Young! Stayin' late this evenin'?"

"No, we're leaving now, Rooney. Good night."

"G' night, Miss Young. Sleep happy."

"Thanks, Rooney."

The old night watchman was a jolly fellow, and everybody liked him. He was very fond of Betty, and the young woman always passed a pleasant word with him.

Rooney entered the room where the amber blocks were. The girl walked with her father down the long corridor. She heard Marable's step behind them.

"Wait for me a moment, father," she said.

She went back, smiling at Marable as she passed him, and entered the door, but remained in the portal and called to Rooney, who was down the laboratory.

He came hurrying to her side at her nervous hail.

"What is it, ma'am?" asked Rooney.

"You'll be careful, won't you, Rooney?" she asked in a low voice.

"Oh, yes, ma'am. I'm always careful. Nobody can get in to harm anything while Rooney's about."[Pg 51]

"I don't mean that. I want you to be careful yourself, when you're in this room to-night."

"Why, miss, what is there to be wary of? Nothin' but some funny lookin' stones, far as I can see."

The young woman was embarrassed by her own impalpable fears, and she took leave of Rooney and rejoined her father, determined to overcome them and dismiss them from her mind.

All the way home and during their evening meal and afterwards, Professor Young poked fun at Betty. She took it good-naturedly, and laughed to see her father in such fine humor. Professor Young was a widower, and Betty was housekeeper in their flat; though a maid did the cooking for them and cleaned the rooms, the young woman planned the meals and saw to it that everything was homelike for them.

After a pleasant evening together, reading, and discussing the new additions to the collection, they went to bed.

Betty Young slept fitfully. She was harassed by dreams, dreams of huge eyes that came closer and closer to her, that at last seemed to engulf her.

She awakened finally from a nap, and started up in her bed. The sun was up, but the clock on the bureau said it was only seven o'clock, too early to arise for the day's work. But then the sound of

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)