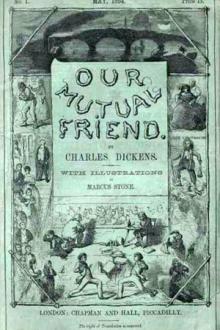

Our Mutual Friend by Charles Dickens (the chimp paradox .txt) 📖

- Author: Charles Dickens

- Performer: -

Book online «Our Mutual Friend by Charles Dickens (the chimp paradox .txt) 📖». Author Charles Dickens

This very exacting member of the fold appeared to be endowed with a sixth sense, in regard of knowing when the Reverend Frank Milvey least desired her company, and with promptitude appearing in his little hall. Consequently, when the Reverend Frank had willingly engaged that he and his wife would accompany Lightwood back, he said, as a matter of course: 'We must make haste to get out, Margaretta, my dear, or we shall be descended on by Mrs Sprodgkin.' To which Mrs Milvey replied, in her pleasantly emphatic way, 'Oh yes, for she is such a marplot, Frank, and does worry so!' Words that were scarcely uttered when their theme was announced as in faithful attendance below, desiring counsel on a spiritual matter. The points on which Mrs Sprodgkin sought elucidation being seldom of a pressing nature (as Who begat Whom, or some information concerning the Amorites), Mrs Milvey on this special occasion resorted to the device of buying her off with a present of tea and sugar, and a loaf and butter. These gifts Mrs Sprodgkin accepted, but still insisted on dutifully remaining in the hall, to curtsey to the Reverend Frank as he came forth. Who, incautiously saying in his genial manner, 'Well, Sally, there you are!' involved himself in a discursive address from Mrs Sprodgkin, revolving around the result that she regarded tea and sugar in the light of myrrh and frankincense, and considered bread and butter identical with locusts and wild honey. Having communicated this edifying piece of information, Mrs Sprodgkin was left still unadjourned in the hall, and Mr and Mrs Milvey hurried in a heated condition to the railway station. All of which is here recorded to the honour of that good Christian pair, representatives of hundreds of other good Christian pairs as conscientious and as useful, who merge the smallness of their work in its greatness, and feel in no danger of losing dignity when they adapt themselves to incomprehensible humbugs.

'Detained at the last moment by one who had a claim upon me,' was the Reverend Frank's apology to Lightwood, taking no thought of himself. To which Mrs Milvey added, taking thought for him, like the championing little wife she was; 'Oh yes, detained at the last moment. But as to the claim, Frank, I must say that I do think you are over-considerate sometimes, and allow that to be a little abused.'

Bella felt conscious, in spite of her late pledge for herself, that her husband's absence would give disagreeable occasion for surprise to the Milveys. Nor could she appear quite at her ease when Mrs Milvey asked:

'How is Mr Rokesmith, and is he gone before us, or does he follow us?'

It becoming necessary, upon this, to send him to bed again and hold him in waiting to be lanced again, Bella did it. But not half as well on the second occasion as on the first; for, a twice-told white one seems almost to become a black one, when you are not used to it.

'Oh dear!' said Mrs Milvey, 'I am SO sorry! Mr Rokesmith took such an interest in Lizzie Hexam, when we were there before. And if we had only known of his face, we could have given him something that would have kept it down long enough for so short a purpose.'

By way of making the white one whiter, Bella hastened to stipulate that he was not in pain. Mrs Milvey was so glad of it.

'I don't know HOW it is,' said Mrs Milvey, 'and I am sure you don't, Frank, but the clergy and their wives seem to cause swelled faces. Whenever I take notice of a child in the school, it seems to me as if its face swelled instantly. Frank never makes acquaintance with a new old woman, but she gets the face-ache. And another thing is, we DO make the poor children sniff so. I don't know how we do it, and I should be so glad not to; but the MORE we take notice of them, the more they sniff. Just as they do when the text is given out.—Frank, that's a schoolmaster. I have seen him somewhere.'

The reference was to a young man of reserved appearance, in a coat and waistcoat of black, and pantaloons of pepper and salt. He had come into the office of the station, from its interior, in an unsettled way, immediately after Lightwood had gone out to the train; and he had been hurriedly reading the printed bills and notices on the wall. He had had a wandering interest in what was said among the people waiting there and passing to and fro. He had drawn nearer, at about the time when Mrs Milvey mentioned Lizzie Hexam, and had remained near, since: though always glancing towards the door by which Lightwood had gone out. He stood with his back towards them, and his gloved hands clasped behind him. There was now so evident a faltering upon him, expressive of indecision whether or no he should express his having heard himself referred to, that Mr Milvey spoke to him.

'I cannot recall your name,' he said, 'but I remember to have seen you in your school.'

'My name is Bradley Headstone, sir,' he replied, backing into a more retired place.

'I ought to have remembered it,' said Mr Milvey, giving him his hand. 'I hope you are well? A little overworked, I am afraid?'

'Yes, I am overworked just at present, sir.'

'Had no play in your last holiday time?'

'No, sir.'

'All work and no play, Mr Headstone, will not make dulness, in your case, I dare say; but it will make dyspepsia, if you don't take care.'

'I will endeavour to take care, sir. Might I beg leave to speak to you, outside, a moment?'

'By all means.'

It was evening, and the office was well lighted. The schoolmaster, who had never remitted his watch on Lightwood's door, now moved by another door to a corner without, where there was more shadow than light; and said, plucking at his gloves:

'One of your ladies, sir, mentioned within my hearing a name that I am acquainted with; I may say, well acquainted with. The name of the sister of an old pupil of mine. He was my pupil for a long time, and has got on and gone upward rapidly. The name of Hexam. The name of Lizzie Hexam.' He seemed to be a shy man, struggling against nervousness, and spoke in a very constrained way. The break he set between his last two sentences was quite embarrassing to his hearer.

'Yes,' replied Mr Milvey. 'We are going down to see her.'

'I gathered as much, sir. I hope there is nothing amiss with the sister of my old pupil? I hope no bereavement has befallen her. I hope she is in no affliction? Has lost no—relation?'

Mr Milvey thought this a man with a very odd manner, and a dark downward look; but he answered in his usual open way.

'I am glad to tell you, Mr Headstone, that the sister of your old pupil has not sustained any such loss. You thought I might be going down to bury some one?'

'That may have been the connexion of ideas, sir, with your clerical character, but I was not conscious of it.—Then you are not, sir?'

A man with a very odd manner indeed, and with a lurking look that was quite oppressive.

'No. In fact,' said Mr Milvey, 'since you are so interested in the sister of your old pupil, I may as well tell you that I am going down to marry her.'

The schoolmaster started back.

'Not to marry her, myself,' said Mr Milvey, with a smile, 'because I have a wife already. To perform the marriage service at her wedding.'

Bradley Headstone caught hold of a pillar behind him. If Mr Milvey knew an ashy face when he saw it, he saw it then.

'You are quite ill, Mr Headstone!'

'It is not much, sir. It will pass over very soon. I am accustomed to be seized with giddiness. Don't let me detain you, sir; I stand in need of no assistance, I thank you. Much obliged by your sparing me these minutes of your time.'

As Mr Milvey, who had no more minutes to spare, made a suitable reply and turned back into the office, he observed the schoolmaster to lean against the pillar with his hat in his hand, and to pull at his neckcloth as if he were trying to tear it off. The Reverend Frank accordingly directed the notice of one of the attendants to him, by saying: 'There is a person outside who seems to be really ill, and to require some help, though he says he does not.'

Lightwood had by this time secured their places, and the departure-bell was about to be rung. They took their seats, and were beginning to move out of the station, when the same attendant came running along the platform, looking into all the carriages.

'Oh! You are here, sir!' he said, springing on the step, and holding the window-frame by his elbow, as the carriage moved. 'That person you pointed out to me is in a fit.'

'I infer from what he told me that he is subject to such attacks. He will come to, in the air, in a little while.'

He was took very bad to be sure, and was biting and knocking about him (the man said) furiously. Would the gentleman give him his card, as he had seen him first? The gentleman did so, with the explanation that he knew no more of the man attacked than that he was a man of a very respectable occupation, who had said he was out of health, as his appearance would of itself have indicated. The attendant received the card, watched his opportunity for sliding down, slid down, and so it ended.

Then, the train rattled among the house-tops, and among the ragged sides of houses torn down to make way for it, and over the swarming streets, and under the fruitful earth, until it shot across the river: bursting over the quiet surface like a bomb-shell, and gone again as if it had exploded in the rush of smoke and steam and glare. A little more, and again it roared across the river, a great rocket: spurning the watery turnings and doublings with ineffable contempt, and going straight to its end, as Father Time goes to his. To whom it is no matter what living waters run high or low, reflect the heavenly lights and darknesses, produce their little growth of weeds and flowers, turn here, turn there, are

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)