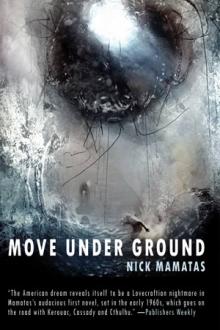

Move Under Ground by Nick Mamatas (books to read romance .TXT) 📖

- Author: Nick Mamatas

- Performer: 0809556731

Book online «Move Under Ground by Nick Mamatas (books to read romance .TXT) 📖». Author Nick Mamatas

“Last requests?” It was the waitress. Behind her, a scattering of townsfolk, all human and oh so sad for it. None of them could stand to even give me a decent look; they all either cast their eyes at the ground, or turned to check out the setting sun. It couldn’t sink too soon for them.

“Whiskey ought to do it,” I told the girl. Neal just smiled like a saint and said, “Peace.”

“Sorry,” she said, then sighed. “Goodland is a dry town.” The creak and whirl of a sharpening stone started up behind me. In my mind’s eye I could see the cook pedaling with one foot, and maybe raising one of his steely knives up to the sky to see it glint, perhaps chuckling at the thought that this town was dry. His basset hound eyes told a different story; in basements, at night, ‘round stills or poker tables full of beer bottles driven in from the next town over by the sheriff’s son, he drank his fill more often than not. He drank just enough, I hoped, to keep him from crying too much after he killed us. He didn’t drink so much, I prayed, because I didn’t want his hand to shake when he laid the blade against my neck. Car tires squealed in the wind, someone escaping with a school kid bundled up in the back, or just another tourist who’d curse an empty diner and drive right on past our scene and find the highway. “Dry town, that’s so funny!” Neal suddenly said, and he laughed with a stutter. “Oh yes, it’ll be wet in a minute though, wet with blood!” His eyes were wild, and his tongue flicked across his lips. Behind us, the cook said, “Settle down, son” and the scrape of his wheeled stone died down to nothing. Even the waitress turned away from us now. She didn’t see a thing when the shooting started, but fell right over, the top half of her head beating her to the ground by an even half-second. The cook went next. I knew because I felt his blood hit my hands and hair and I heard him thump down like a pig he’d just stuck. Most of the others managed to run off, but a few got picked away, heads blooming with blood, legs managing to run a step or two before getting the news that they were already dead and finally folding like a marionette with cut strings. The streets of Goodland echoed with the reports of gunfire; my old friend of a thug ran the wrong way and into a bullet, one that sunk right into his forehead. He fell cross-eyed, trying to see what just did him in.

Finally, after the crack and thunder of guns stopped ringing in the street, Bill Burroughs walked up to us, his face still hangdog and sallow like I remembered. His hair was swooped over and damp from sweat, the peculiar sweat of the junky that Burroughs always looked like he had just been dipped in. In his hands, he carried a pair of long pistols. Bill hadn’t shaved in a few days and didn’t smile when he saw us. He U-turned and said “Fellas?” More a question than anything else.

Neal smiled. “The Old Bull! I knew you’d make it. I tried to tell these fine upstanding—well, they’re downbleeding now—but I tried to tell these citizens that they were going to die. They just didn’t believe me. Not even old cookie.”

“Burroughs, untie us please,” I said. Haven’t had much use for Bill lately, but I was ready to hug the old queen. He shrugged and tucked his guns into his waistband like an old movie cowboy (or like someone who wants to be sure that he shoots his pecker off—if one don’t get it, the other gun will) and untied us silently, like he was waiting. Neal was just pleased as punch, as happy that Bill came in and blew away seven people who were ready to carve us to pieces as he’d be if he just saw old Bill half on the nod and staggering down the streets of Frisco.

So I asked, “Damn, how did you know? How did you know to come out all the way to Goodland, armed for bear, just in time to save us from some sort of sacrifice.” My binds fell and Bill threw the ropes to the ground. “Neal wrote me a letter a few weeks ago, telling me to meet him here. He said there was something important for me to shoot. Doesn’t seem like it, really,” he said, his voice just like a frog who can’t swing. He took it slow, wandering more than walking over to Neal, and untied him too. I looked around for the old lady; she wasn’t among the bodies. I guess she got away somehow—did Bill even aim at her, or was she lucky? Real lucky, yeah, like all God-fearing folk of Goodland, who just want to live their little lives under the spiked and hooved boots of their horrible alien overlords. “How’d you like the old William Tell routine?” he asked, but if he meant that question in dark humor his voice didn’t betray it. Bill really wanted to know. I didn’t want to tell him, I wanted to think of something else—anything other than those poor fools falling to the power of the gun.

The kids, I thought, and that surprised me, because I thought it the same time Neal said it: “The kids!” And in the space of one horrible breath, another gong sounded in the distance and I saw the truth. There were no hostages, just a school full of little bodies, all wrinkled and thin from the rot. They’d just been locked away and starved, wailing and whining for mama. Then they got nasty with each other, the boys holding down the girls and eating their hair and biting their skin, just to have something to eat. The beetlemen didn’t have to torture the little tykes, those sweet cherubs with their cheeks rosy and slick with tears. They already knew the tango of life and death. They ate their own crap, and the paper, and chalk, and drank pee and then just upped and died, bodies so little and so desperate to grow that they burned themselves out.

“We have to save them!” Neal said, frantic again with the wave of a new idea. “They took my pistol, Bill, give me one of yours.” He reached for Bill’s pants, but Bill sidestepped and held up his hands, “Neal, really. I passed by the school. Remember? It was in your letter too. You already know.”

I knew too, thanks to the buzz of Marie-bee, the demon who told me everything she felt I needed to know just days ago in Big Sur. The Goodland cult got no pleasure from those kids; they didn’t torture the third-graders for secrets, they didn’t drink sweet young blood like nectar; the mayor and the fire chief, the banker and the librarian, they just surrendered their souls to the Dark Dream and forgot. They forgot that babes need to eat, that they need hugs and baseball and to be told to wash behind their ears or else they won’t do it. Some demon impulse told them to collect the kids and trap them behind a spell that could turn the air to a wall of whips. And then, nothing. The cult knew its place was in the stars; they spent their days dancing under the writhing invisible tentacles that filled the sky in their offices—every paper pushed a celebration. And their nights, oh the nights. Evenings the cult spent in their homes, puppets acting out a shadow life, just to make sure everything looked normal. Act natural, the bleary-eyed god from the sea told them, and the good folks of Goodland don’t step outdoors at night. So they stayed in, and nobody even thought to bring the children food, and the kids burned with hunger and then with rage, then they howled and died.

Neal knew too, once, in a burst of ecstatic prophecy, but now, back in the mundane world, he had to go see for himself. Bill and I just stood around, not saying much, while Neal yipped and ran off, collapsing in a heap, and then running off around the corner to where he thought the school was. A minute later, just as Bill was opening his mouth to say something or other, Neal ran by again like Harpo Marx, heading in the opposite direction. Bill shut up at that. I rubbed my wrists raw and waited—Neal would be fine. His special sight would show him the whirling blades that surrounded the school and he could pick his way through them, ducking and hopping and rolling, as easy as you please.

The looks on the corpses’ faces were just unbearable. It wasn’t even the fear that lasted like rubber cooling in a man-shaped mold with eyes and a nose, it was the disappointment. The cultists had told them, after all, they it would all be okay. No more empty spaces at the dinner table, no more empty Sunday School (heck, their prayers would be answered in a way they could point to for years later—“Yep, and then Clem was returned to us, just in time for chores, hale and happy as you please”) and all they’d have to do is find two strangers and butcher them. That’s what they were disappointed in, these bodies, the hard fact that life wasn’t fair. One woman, Bill had shot her in the neck, so I could still see that her mouth was a line of desperate consternation, she had a novel written in her expression. Come on, Cookie, I could see her screaming in her mind, even as the bullets rained down and the other members of the Ladies’ Auxilliary fell on either side of her. Kill them! Kill them with your blessed butcher’s knife and the bullets will stop. Kill them and Alice will be home by the time I run back there, and we can all have supper like a family again. Life isn’t fair, she finally realized as a bullet ate its way through her in a split-second. Life wasn’t fair, and not because Neal and poor old me were trussed up and about to be skinned alive either. Life wasn’t fair because even the soul-raped slaves of the Dreamer In The Darkness couldn’t be counted on to keep their promises, and to let their babies go free, safe and sound.

Soon Neal came back eventually, when the moon was bright and high and his head low, hands in his pockets. He walked up without saying the word, and I swear, that was the first time I’d ever seen Neal sober and speechless at the same time. Even his head, when he lifted it, even his chin that drooped just a little more than usual, were sad. He was sad, his eyes that no longer reflected the cosmic madness he sought in the starry belly of Azathoth were sad. “I can’t put that in my book,” he told me. Bill scratched his nose and looked on.

“I just can’t,” Neal said. “It

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)