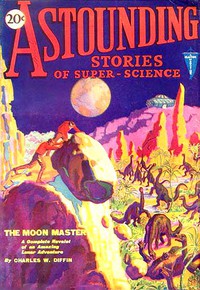

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930 by Various (novels for teenagers TXT) 📖

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930 by Various (novels for teenagers TXT) 📖». Author Various

"Hardly. They're not quite the apparel for so long a stroll. You haven't seen all the marvels yet. Come along!"

e led the way through the patio, beside the pool in which our strange visitor from the depths had lived during her brief stay with us, and out into the open again. As we neared the sea, I became aware, for the first time, of a faint, muffled hammering sound, and I glanced at Mercer inquiringly.

"Just a second," he smiled. "Then—there she is, Taylor!"

I stood still and stared. In a little cove, cradled in a cunning, spidery structure of wood, a submarine rested upon the ways.

"Good Lord!" I exclaimed. "You're going into this right, Mercer!"

"Yes. Because I think it's immensely worth while. But come along and let me show you the Santa Maria—named after the flagship of Columbus' little fleet. Come on!"

Two men with army automatics strapped significantly to their belts nodded courteously as we came up. They were the only men in sight, but from the hammering going on inside there must have been quite a sizeable crew busy in the interior. A couple of raw pine shacks, some little distance away, provided quarters for, I judged, twenty or thirty men.

"Had her shipped down in pieces," explained Mercer. "The boat that brought it lay to off shore and we lightered the parts ashore. A tremendous job. But she'll be ready for the water in a week; ten days at the latest."

"You're a wonder," I said, and I meant it.

ercer patted the red-leaded side of the submarine affectionately. "Later," he said, "I'll take you inside, but they're busy as the devil in there, and the sound of the hammers fairly makes your head ring. You'll see it all later, anyway—if you feel you'd like to share the adventure with me?"

"Listen," I grinned as we turned back towards the house, "it'll take more than those two lads with the pop-guns to keep me out of the Santa Maria when she sails—or dives, or whatever it is she's supposed to do!"

Mercer laughed softly, and we walked the rest of the way in silence. I imagine we were both pretty busy with our thoughts; I know that I was. And several times, as we walked along, I looked back over my shoulder towards the ungainly red monster straddling on her spindling wooden legs—and towards the smiling Atlantic, glistening serenely in the sun.

ercer was so busy with a thousand and one details that I found myself very much in the way if I followed him around, so I decided to loaf.

For weeks after we had put our strange girl visitor back into the sea from whence Mercer had taken her, I had watched from a comfortable seat well above the high-water mark that commanded that section of shore. For I had felt sure by that last strange gesture of hers that she meant to return.

I located my old seat, and I found that it had been used a great deal since I had left it. There were whole winnows of cigarette butts, some of them quite fresh, all around. Mercer, cold-blooded scientist as he was, had hoped[155] against hope that she would return too.

It was a very comfortable seat, in the shade of a little cluster of palms, and for the next several days I spent most of my time there, reading and smoking—and watching. No matter how interesting the book, I found myself, every few seconds, lifting my eyes to search the beach and the sea.

I am not sure, but I think it was the eighth day after my arrival that I looked up and saw, for the first time, something besides the smiling beach and the ceaseless procession of incoming rollers. For an instant I doubted what I saw; then, with a cry that stuck in my throat, I dropped my book unheeded to the sand and raced towards the shore.

he was there! White and slim, her pale gold hair clinging to her body and gleaming like polished metal in the sun, she stood for a moment, while the spray frothed at her thighs. Behind her, crouching below the surface, I could distinguish two other forms. She had returned, and not alone!

One long, slim arm shot out toward me, held level with the shoulder: the well-remembered gesture of greeting. Then she too crouched below the surface that she might breathe.

As I ran out onto the wet sand, the waves splashing around my ankles all unheeded, she rose again, and now I could see her lovely smile, and her dark, glowing eyes. I was babbling—I do not know what. Before I could reach her, she smiled and sank again below the surface.

I waded on out, laughing excitedly, and as I came close to her, she bobbed up again out of the spray, and we greeted each other in the manner of her people, hands outstretched, each gripping the shoulder of the other.

She made a quick motion then, with both hands, as though she placed a cap upon the shining glory of her head, and I understood in an instant what she wished: the antenna of Mercer's thought-telegraph, by the aid of which she had told us the story of herself and her people.

nodded and smiled, and pointed to the spot where she stood, trying to show her by my expression that I understood, and by my gesture, that she was to wait here for me. She smiled and nodded in return, and crouched again below the surface of the heaving sea.

As I turned toward the beach, I caught a momentary glimpse of the two who had come with her. They were a man and a woman, watching me with wide, half-curious, half-frightened eyes. I recognized them instantly from the picture she had impressed upon my mind nearly a year ago. She had brought with her on her journey her mother and her father.

Stumbling, my legs shaking with excitement, I ran through the water. With my wet trousers flapping against my ankles, I sprinted towards the house.

I found Mercer in the laboratory. He looked up as I came rushing in, wet from the shoulders down, and I saw his eyes grow suddenly wide.

opened my mouth to speak, but I was breathless. And Mercer took the words from my mouth before I could utter them.

"She's come back!" he cried. "She's come back! Taylor—she has?" He gripped me, his fingers like steel clamps, shaking me with his amazing strength.

"Yes." I found my breath and my voice at the same instant. "She's there, just where we put her into the sea, and there are two others with her—her mother and her father. Come on, Mercer, and bring your thought gadget!"

"I can't!" he groaned. "I've built an improvement on it into the diving armor, and a central instrument on the sub, but the old apparatus is strewn all over the table, here, just as it was[156] when we used it the other time. We'll have to bring her here."

"Get a basin, then!" I said. "We'll carry her back to the pool just as we took her from it. Hurry!"

And we did just that. Mercer snatched up a huge glass basin used in his chemistry experiments, and we raced down to the shore. As well as we could we explained our wishes, and she smiled her quick smile of understanding. Crouching beneath the water, she turned to her companions, and I could see her throat move as she spoke to them. They seemed to protest, dubious and frightened, but in the end she seemed to reassure them, and we picked her up, swathed in her hair as in a silken gown, and carried her, her head immersed in the basin of water, that she might breathe in comfort, to the pool.

It all took but a few minutes, but it seemed hours. Mercer's hands were shaking as he handed me the antenna for the girl and another for myself, and his teeth were chattering as he spoke.

"Hurry, Taylor!" he said. "I've set the switch so that she can do the sending, while we receive. Quickly, man!"

leaped into the pool and adjusted the antenna on her head, making sure that the four electrodes of the crossed curved members pressed against the front and back and both sides of her head. Then, hastily, I climbed out of the pool, seated myself on its edge, and put on my own antenna.

Perhaps I should say at this time that Mercer's device for conveying thought could do no more than convey what was in the mind of the person sending. Mercer and I could convey actual words and sentences, because we understood each other's language, and by thinking in words, we conveyed our thoughts in words. One received the impression, almost, of having heard actual speech.

We could not communicate with the girl in this fashion, however, for we did not understand her speech. She had to convey her thoughts to us by means of mental pictures which told her story. And this is the story of her pictures unfolded.

First, in sketchy, half-formed pictures, I saw her return to the village, of her people; her welcome there, with curious crowds around her, questioning her. Their incredulous expressions as she told them of her experience were ludicrous. Her meeting with her father and mother brought a little catch to my throat, and I looked across the pool at Mercer. I knew that he, too, was glad that we bad put her back into the sea when she wished to go.

hese pictures faded hastily, and for a moment there was only the circular swirling as of gray mist; that was the symbol she adopted to denote the passing of time. Then, slowly, the picture cleared.

It was the same village I had seen before, with its ragged, warped, narrow streets, and its row of dome-shaped houses, for all the world like Eskimo igloos, but made of coral and various forms of vegetation. At the outskirts of the village I could see the gently moving, shadowy forms of weird submarine growths, and the quick darting shapes of innumerable fishes.

Some few people were moving along the streets, walking with oddly springy steps. Others, a larger number, darted here and there above the roofs, some hovering in the water as gulls hover in the air, lazily, but the majority apparently on business or work to be executed with dispatch.

Suddenly, into the midst of this peaceful scene, three figures came darting. They were not like the people of the village, for they were smaller, and instead of being gracefully slim they were short and powerful in build. They were not white like the people of the girl's village, but swarthy, and they were dressed in a sort of tight-fitting shirt of gleaming leather—shark-skin, I learned later. They carried, tucked[157] through a sort of belt made of twisted vegetation, two long, slim knives of pointed stone or bone.

ut it was not until they seemed to come close to me that I saw the great point of difference. Their faces were scarcely human. The nose had become rudimentary, leaving a large, blank expanse in the middle of their faces that gave them a peculiarly hideous expression. Their eyes were almost perfectly round, and very fierce, and their mouths huge and fishlike. Beneath their sharp, jutting jaws, between the angle of the jaws and a spot beneath the ears, were huge, longitudinal slits, that intermittently showed blood-red, like fresh gashes cut in the sides of their throats. I could see even the hard, bony cover that protected these slits, and I realized that these were gills! Here were representatives of a people that had gone back to the sea ages before the people of the girl's village.

Their coming caused a sort of panic in the village, and the three noseless creatures strode down the principal street grinning hugely, glancing from right to left, and showing their sharp pointed teeth. They looked more like sharks than like human beings.

A committee of five gray old men met the visitors, and conducted them into one of the larger houses. Insolently, the leader of the three shark-faced creatures made demands, and the scene changed swiftly to make clear the nature of those demands.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)