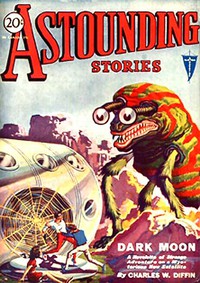

Astounding Stories, August, 1931 by Various (easy to read books for adults list .txt) 📖

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories, August, 1931 by Various (easy to read books for adults list .txt) 📖». Author Various

An ominous click sounded in his ears. Then silence.

"Hello! Hello there!" he shouted. "Can you hear me up on the boat?"

But no answer came back. The line remained dead. The strange fish had cut George Abbot's last contact with the upper world. The grapple-hooks could never find him now, for there was now not even a telephone cable to guide them down to his sphere.

The realization that he was hopelessly lost, and that he had not much longer to live, came as a real relief to him, after the last few moments of frantic uncertainty.

oping that his sphere would eventually be found, even though too late to do him any good, he set assiduously to work jotting down all the details which he could remember of those strange denizens of the deep, the man-handed sharks, which he was now firmly convinced were the cause of his present predicament.

He stared out through one of his windows into the brilliant blue darkness, but did not turn on his flashlight. How near were these enemies of his, he wondered?

The presence of those menacing man-sharks, just outside the four-inch-thick steel shell, which withstood a ton of pressure for each square inch of its surface, began to obsess young Abbot. What were they doing out there in the watery-blue midnight? Perhaps, having secured his sphere as a scientific specimen, they were already preparing to cut into it so as to see what was inside. That[153] these fish could cut through four inches of steel was not so improbable as it sounded, for had they not already succeeded in severing a rubber cable an inch and a half thick, containing two heavy copper wires, and also two inches of the finest, non-kinking steel rope!

The young scientist flashed his pocket torch out through the thick quartz pane, but his enemies were nowhere in sight. Then he fell to calculating his oxygen supply. His normal consumption was about half a quart per minute, at which rate his two tanks would be good for thirty-six hours. His chemical racks contained enough soda-lime to absorb the excess carbon dioxide, enough calcium chloride to keep down the humidity and enough charcoal to sweeten the body odors for much more than that period.

For a moment, the thought of these facts encouraged him. He had been down less than two hours. Perhaps the boat above him could affect his rescue in the more than thirty-four hours which remained!

ut then he realized that he had failed to take into consideration the near-freezing temperature of the ocean depths. This temperature he knew to be in the neighborhood of 39 degrees Fahrenheit—even though no thermometer hung outside his window, as none could withstand the frightful pressures at the bottom of the sea. For it is one of the remarkable facts of inductive science that man has been able to figure out a priori that the temperature at all deep points of the ocean, tropic as well as arctic, must always be stable at approximately 39 degrees.

Abbot was clad only in a light cotton sailor suit, and now that his source of heat had been cut off by the severing of his power lines, his prison was rapidly becoming unbearably chilly. His thick steel sphere constituted such a perfect transmitter of heat that he might almost as well have been actually swimming in water of 39 degrees temperature, so far as comfort was concerned.

Abbot's emotions ran all the gamut from stupefaction, through dull calmness, clear-headed thought, intense but aimless mental activity, nervousness, frenzy, and insane delirium, back to stupefaction again.

During one of his periods of calmness, he figured out what an almost total impossibility there was of the chance that his ship, one mile above him on the surface, could ever find his sphere with grappling hooks. Yet he prayed for that chance. A single chance in a million sometimes does happen.

everal hours had by now elapsed since the parting of the young scientist's cables. It was bitterly cold inside the sphere. In order to keep warm, he had to exercise during his calm moments as systematically as his cramped quarters would permit. During his frantic moments he got plenty of exercise automatically. And of course all this movement used up more than the normal amount of oxygen, so that he was forced to open the valves on his tanks to two or three times their normal flow. His span of further life was thereby cut to ten or twelve hours, if indeed he could keep himself warm for that long.

Why didn't the people on the boat do something!

He was just about to indulge in one of his frantic fits of despair, when he heard or felt—the two senses being strangely commingled in his present situation—a clank or thump upon the top of his bathysphere. Instantly hope flooded him. Could it be that the one chance in a million had actually happened, and that a grapple from the boat above had actually found him?

With feverish expectation, he pressed the button of his little electric[154] pocket flashlight, and sent its feeble beam out through one of the quartz-glass windows into the blue-black depths beyond.

No hooks in front of this window. He tried the others. No hooks there, either. But he did see plenty of the superhuman fish. Eighteen of them, he counted, in sight at one time. And also two huge snake-like creatures with crested backs and maned heads, veritable sea-serpents.

As there was nothing the young man could do to assist in the grappling of his sphere by his friends in the boat above, he devoted his time to jotting down a detailed description of these two new beasts and of their behavior.

One of the sharks appeared to be leading or driving them up to the bathysphere; and when they got close enough, Abbot was surprised to see that they wore what appeared to be a harness!

he clanking upon the bathysphere continued, and now the young man learned its cause. It was not the grapple hooks from his ship, but chains—chains which the man-armed sharks were wrapping around the bathysphere.

Two more of the harnessed sea-serpents swam into view, and these two were hitched to a flat cart: an actual cart with wheels. The chains were attached to the harness of the original two beasts; they swam upward and disappeared from view; and the sphere slowly rose from the mucky bottom of the sea, to be lowered again squarely on top of the cart. The cart jerked forward, and a journey over the ocean floor began.

Then the little pocket torch dimmed to a dull red glow, and the scene outside faded gradually from view. Abbot switched off the now useless light and set to work with scientific precision to record all these unbelievable events.

In his interest and excitement, he had forgotten the ever-increasing cold; but gradually, as he wrote, the frigidity of his surroundings was forced on his consciousness. He turned on more oxygen, and exercised frantically. Meanwhile the cart, carrying his bathysphere, bumped along over an uneven road.

From time to time, he tried his almost exhausted little light, but its dim red beam was completely absorbed by the blue of the ocean depths, and he could make out nothing except two bulking indistinct shapes, writhing on ahead of him. Finally even this degree of visibility failed, and he could see absolutely nothing outside.

He was now so chilled and numb that he could no longer write. With a last effort, he noted down that fact, and then put the book away in its rack.

He began to feel drowsy. Rousing himself, he turned on more oxygen. The effect was exhilaration and a feeling of silly joy. He began to babble drunkenly to himself. His head swam. His mind was in a daze.

t seemed hours later when he awoke. Ahead of him in the distance there was a dim pale-blue light, against which there could be seen, in silhouette, the forms of the two serpentine steeds and their fish-like drivers. Abbot's hands and feet were completely numb, but his head was clear.

As they drew nearer to the light, it gradually took form, until it turned out to be the mouth of a cave. The cart entered it.

Down a long tunnel they progressed, the light getting brighter and brighter as they advanced. The color of the light became a golden green. The rough stone walls of the tunnel could now be seen; and finally there appeared, ahead, two semicircular doors, swung back against the sides of the passage.[155]

Beyond these doors, the tunnel walls were smooth and exactly cylindrical, and on the ceiling there were many luminous tubes, which lit up the place as brightly as daylight. The cart came to a stop.

The young scientist could now see with surprising distinctness his captors and their serpentine steeds, and even the details of the chains and the harness. He tried to pick up his diary, so as to jot down some points which he had theretofore missed; but his hands were too numb. But at least he could keep on observing; so he glued his eyes to the thick quartz window-pane once more.

A short distance ahead in the passage there was another pair of doors. Presently these swung open and the cavalcade moved forward. Five or six successive pairs of doors were passed in this manner, and then the sea-serpents began to thrash about and become almost unmanageable. It was evident that some change not to their liking had taken place in their surroundings.

t last, as one of the portals swung open, young Abbot saw what appeared to be four deep-sea diving-suits. Could these suits contain human beings? And if so, who? It seemed incredible, for no diving-suit had ever been devised in which a man could descend to the depth of one mile, and live.

These four figures, whatever they were, came stolidly forward and took charge of the cart. One of the sharks swam up to them and appeared to talk to them with its hands. Then the sharks unhitched the two sea-serpents and led them to the rear, and Abbot saw them no more.

The four divers picked up the chains, and slowly towed the cart forward, their clumsy, ponderous movements contrasting markedly with the swift and sure swishings which had characterized the man-sharks and their snake-like steeds.

Several more pairs of doors were passed, and then there met them four figures in less cumbersome diving-suits, like those ordinarily used by men just below the surface of the sea. One of the deep-sea divers then pressed his face close to the outside of one of the windows of the bathysphere, as though to take a look inside; but the four newcomers waved him away, and hurriedly picked up the chains. Nevertheless, in that brief instant, Abbot had seen within the head-piece of the diver what appeared to be a bearded human face.

Several more pairs of doors were passed. The four deep-sea divers floundered along beside the cart, quite evidently having more and more difficulty of locomotion as each successive doorway was passed, until finally they lay down and were left behind.

At last the procession entered a section of tunnel which was square, instead of circular, and in which there was a wide shelf along one side about three feet above the floor. The four divers then dropped the chains, and one by one took a look at Abbot through his window.

And he at the same time took a most interested look at them.

They had unmistakable human faces!

e must be dreaming! For even if Osborne was right about his supposed super-race at the bottom of the sea, this race could not be human, for the pressures here would be entirely too great. No human being could possibly stand two thousand pounds per square inch!

Having satisfied their curiosity, the four divers pulled themselves up onto the shelf, and sat there in a row with their legs hanging over.

Abbot glanced upward at the ceiling lights, but these had become strangely blurred. There seemed to be an opaque barrier above him, and this barrier seemed to be slowly descending.[156] The lights blurred out completely, and were replaced by a diffused illumination over the entire ripply barrier. And then it dawned on the young man that this descending sheet of silver was the surface of the water. He was in a lock,

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)