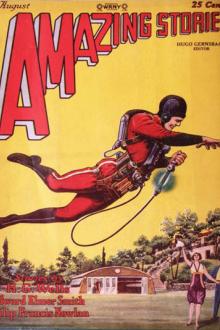

The Skylark of Space by Lee Hawkins Garby and E. E. Smith (novels for teenagers txt) 📖

Book online «The Skylark of Space by Lee Hawkins Garby and E. E. Smith (novels for teenagers txt) 📖». Author Lee Hawkins Garby and E. E. Smith

Margaret Spencer, weakened by her imprisonment, was the first to lose consciousness, and soon afterward Dorothy felt her senses leave her. A half-minute, in the course of which six mighty surges were felt, as more of the power of the doubled motor was released, and Crane had gone, calmly analyzing his sensations to the last. After a time DuQuesne also lapsed into unconsciousness, making no particular effort to avoid it, as he knew that the involuntary muscles would function quite as well without the direction of the will. Seaton, although he knew it was useless, fought to keep his senses as long as possible, counting the impulses he felt as the levers were advanced.

"Thirty-two." He felt exactly as he had before, when he had advanced the lever for the last time.

"Thirty-three." A giant hand shut off his breath completely, though he was fighting to his utmost for air. An intolerable weight rested upon his eyeballs, forcing them backward into his head. The universe whirled about him in dizzy circles—orange and black and green stars flashed before his bursting eyes.

"Thirty-four." The stars became more brilliant and of more variegated colors, and a giant pen dipped in fire was writing equations and mathematico-chemical symbols upon his quivering brain. He joined the circling universe, which he had hitherto kept away from him by main strength, and whirled about his own body, tracing a logarithmic spiral with infinite velocity—leaving his body an infinite distance behind.

"Thirty-five." The stars and the fiery pen exploded in a wild coruscation of searing, blinding light and he plunged from his spiral into a black abyss.

In spite of the terrific stress put upon the machine, every part functioned perfectly, and soon after Seaton had lost consciousness the vessel began to draw away from the sinister globe; slowly at first, faster and faster as more and more of the almost unlimited power of the mighty motor was released. Soon the levers were out to the last notch and the machine was exerting its maximum effort. One hour and an observer upon the Skylark would have seen that the apparent size of the massive unknown world was rapidly decreasing; twenty hours and it was so far away as to be invisible, though its effect was still great; forty hours and the effect was slight; sixty hours and the Skylark was out of range of the slightest measurable force of the monster it had left.

Hurtled onward by the inconceivable power of the unleashed copper demon in its center, the Skylark flew through the infinite reaches of interstellar space with an unthinkable, almost incalculable velocity—beside which the velocity of light was as that of a snail to that of a rifle bullet; a velocity augmented every second by a quantity almost double that of light itself.

CHAPTER XI Through Space Into the CarboniferousSeaton opened his eyes and gazed about him wonderingly. Only half conscious, bruised and sore in every part of his body, he could not at first realize what had happened. Instinctively drawing a deep breath, he coughed and choked as the undiluted oxygen filled his lungs, bringing with it a complete understanding of the situation. Knowing from the lack of any apparent motion that the power had been sufficient to pull the car away from that fatal globe, his first thought was for Dorothy, and he tore off his helmet and turned toward her. The force of even that slight movement, wafted him gently into the air where he hung suspended several minutes before his struggles enabled him to clutch a post and draw himself down to the floor. A quick glance around informed him that Dorothy, as well as the others, was still unconscious. Making his way rapidly to her, he[544] placed her face downward upon the floor and began artificial respiration. Very soon he was rewarded by the coughing he had longed to hear. He tore off her helmet and clasped her to his breast in an agony of relief, while she sobbed convulsively upon his shoulder. The first ecstasy of their greeting over, Dorothy started guiltily.

"Oh, Dick!" she exclaimed. "How about Peggy? You must see how she is!"

"Never mind," answered Crane's voice cheerily. "She is coming to nicely."

Glancing around quickly, they saw that Crane had already revived the stranger, and that DuQuesne was not in sight. Dorothy blushed, the vivid wave of color rising to her glorious hair, and hastily disengaged her arms from around her lover's neck, drawing away from him. Seaton, also blushing, dropped his arms, and Dorothy floated away from him, frantically clutching at a brace just beyond reach.

"Pull me down, Dick!" she called, laughing gaily.

Seaton, seizing her instinctively, neglected his own anchorage and they hung in the air together, while Crane and Margaret, each holding a strap, laughed with unrestrained merriment.

"Tweet, tweet—I'm a canary!" chuckled Seaton. "Throw us a rope!"

"A Dicky-bird, you mean," interposed Dorothy.

"I knew that you were a sleight-of-hand expert, Dick, but I did not know that levitation was one of your specialties," remarked Crane with mock gravity. "That is a peculiar pose you are holding now. What are you doing—sitting on an imaginary pedestal?"

"I'll be sitting on your neck if you don't get a wiggle on with that rope!" retorted Seaton, but before Crane had time to obey the command the floating couple had approached close enough to the ceiling so that Seaton, with a slight pressure of his hand against the leather, sent them floating back to the floor, within reach of one of the handrails.

Seaton made his way to the power-plant, lifted in one of the remaining bars, and applied a little power. The Skylark seemed to jump under them, then it seemed as though they were back on Earth—everything had its normal weight once more, as the amount of power applied was just enough to equal the acceleration of gravity. After this fact had been explained, Dorothy turned to Margaret.

"Now that we are able to act intelligently, the party should be introduced to each other. Peggy, this is Dr. Dick Seaton, and this is Mr. Martin Crane. Boys, this is Miss Margaret Spencer, a dear friend of mine. These are the boys I have told you so much about, Peggy. Dick knows all about atoms and things; he found out how to make the Skylark go. Martin, who is quite a wonderful inventor, made the engines and things for it."

"I may have heard of Mr. Crane," replied Margaret eagerly. "My father was an inventor, and I have heard him speak of a man named Crane who invented a lot of instruments for airplanes. He used to say that the Crane instruments revolutionized flying. I wonder if you are that Mr. Crane?"

"That is rather unjustifiably high praise, Miss Spencer," replied Crane, "but as I have been guilty of one or two things along that line, I may be the man he meant."

"Pardon me if I seem to change the subject," put in Seaton, "but where's DuQuesne?"

"We came to at the same time, and he went into the galley to fix up something to eat."

"Good for him!" exclaimed Dorothy. "I'm simply starved to death. I would have been demanding food long ago, but I have so many aches and pains that I didn't realize how hungry I was until you mentioned it. Come on, Peggy, I know where our room is. Let's go powder our noses while these bewhiskered gentlemen reap their beards. Did you bring along any of my clothes, Dick, or did you forget them in the excitement?"

"I didn't think anything about clothes, but Martin did. You'll find your whole wardrobe in your room. I'm with you, Dot, on that eating proposition—I'm hungry enough to eat the jamb off the door!"

After the girls had gone, Seaton and Crane went to their rooms, where they exercised vigorously to restore the circulation to their numbed bodies, shaved, bathed, and returned to the saloon feeling like new men. They found the girls already there, seated at one of the windows.

"Hail and greeting!" cried Dorothy at sight of them. "I hardly recognized you without your whiskers. Do hurry over here and look out this perfectly wonderful window. Did you ever in your born days see anything like this sight? Now that I'm not scared pea-green, I can enjoy it thoroughly!"

The two men joined the girls and peered out into space through the window, which was completely invisible, so clear was the glass. As the four heads bent, so close together, an awed silence fell upon the little group. For the blackness of the interstellar void was not the dark of an earthly night, but the absolute black of the absence of all light, beside which the black of platinum dust is pale and gray; and laid upon this velvet were the jewel stars. They were not the twinkling, scintillating beauties of the earthly sky, but minute points, so small as to seem dimensionless, yet of dazzling brilliance. Without the interference of the air, their rays met the eye steadily and much of the effect of comparative distance was lost. All seemed nearer and there was no hint of familiarity in their arrangement. Like gems thrown upon darkness they shone in multi-colored beauty upon the daring wanderers, who stood in their car as easily as though they were upon their parent Earth, and gazed upon a sight never before seen by eye of man nor pictured in his imaginings.

Through the daze of their wonder, a thought smote Seaton like a blow from a fist. His eyes leaped to the instrument board and he exclaimed:

"Look there, Mart! We're heading almost directly away from the Earth, and we must be making billions of miles per second. After we lost consciousness, the attraction of that big dud back there would swing us around, of course, but the bar should have stayed pointed somewhere near the Earth, as I left it. Do you suppose it could have shifted the gyroscopes?"[545]

"It not only could have, it did," replied Crane, turning the bar until it again pointed parallel with the object-compass which bore upon the Earth. "Look at the board. The angle has been changed through nearly half a circumference. We couldn't carry gyroscopes heavy enough to counteract that force."

"But they were heavier there—Oh, sure, you're right. It's mass, not weight, that counts. But we sure are in one fine, large jam now. Instead of being half-way back to the Earth we're—where are we, anyway?"

They made a reading on an object-compass focused upon the Earth. Seaton's face lengthened as seconds passed. When it had come to rest, both men calculated the distance.

"What d'you make it, Mart? I'm afraid to tell you my result."

"Forty-six point twenty-seven light-centuries," replied Crane, calmly. "Right?"

"Right, and the time was 11:32 P. M. of Thursday, by the chronometer there. We'll time it again after a while and see how fast we're traveling. It's a good thing you built the ship's chronometers to stand any kind of stress. My watch is a total loss. Yours is, too?"

"All of our watches must be broken. We will have to repair them as soon as we get time."

"Well, let's eat next! No human being can stand my aching void much longer. How about you, Dot?"

"Yes, for Cat's sake, let's get busy!" she mimicked him gaily. "Doctor DuQuesne's had dinner ready for ages, and we're all dying by inches of hunger."

The wanderers, battered, bruised, and sore, seated themselves at a folding table, Seaton keeping a watchful eye upon the bar and upon the course, while enjoying Dorothy's presence to the full. Crane and Margaret talked easily, but at intervals. Save when directly addressed. DuQuesne maintained silence—not the silence of one who knows himself to be an intruder, but the silence of perfect self-sufficiency. The meal over, the girls washed the dishes and busied themselves in the galley. Seaton and Crane made another observation upon the Earth, requesting DuQuesne to stay out of the "engine room" as they called the partially-enclosed space surrounding the main instrument board, where were located the object-compasses and the mechanism controlling the attractor, about which DuQuesne knew nothing. As they rejoined DuQuesne in the main compartment, Seaton said:

"DuQuesne, we're nearly five thousand light-years away from the Earth, and are getting farther at the rate of about one light-year per minute."

"I suppose that it would be poor technique to ask how you know?"

"It would—very poor. Our figures are right. The difficulty is that we have only four bars left—enough to stop us and a little to spare, but not nearly enough to get back with, even if we could take a chance on drifting straight that far without being swung off—which, of course, is impossible."

"That means that we must land somewhere and dig some copper, then."

"Exactly.

"The first thing to do is to find a place to land."

Seaton picked

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)