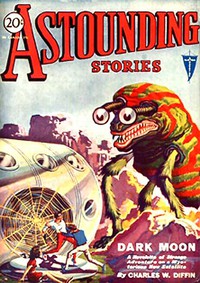

Astounding Stories, May, 1931 by Various (list of ebook readers TXT) 📖

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories, May, 1931 by Various (list of ebook readers TXT) 📖». Author Various

I wonder if that were His purpose....

How, scientifically, do we progress along the Time-scroll? That I can make clear by a simple analogy.

Suppose you conceive Time as a narrow strip of metal, laid flat and extending for an infinite length. For simplicity, picture it with two ends. One end of the metal band is very cold; the other end is very hot. And every graduation of temperature is in between.

This temperature is caused, let us say, by the vibration of every tiny particle with which the band is composed. Thus, at every point along the band, the vibration of its particles would be just a little different from every other point.

onceive, now, a material body—your body, for instance. Every tiny particle of which it is constructed, is vibrating. I mean no simple vibration. Do not picture the physical swing of a pendulum. Rather, the intricate total of all the movements of every tiny electron of which your body is built. Remember, in the last analysis, your body is merely movement—vibration—a vortex of Nothingness. You have, then, a certain vibratory factor.

You take your place then upon the Time-scroll at a point where your inherent vibratory factor is compatible with the scroll. You are in tune; in tune as a radio receiver tunes in with etheric waves to make them audible. Or, to keep the heat analogy, it is as though the scroll, at the point where the temperature is 70°F, will tolerate nothing upon it save entities of that register.

And so, at that point on the scroll, the myriad things, in myriad positions which make up the Cosmos, lie quiescent. But their existence is only instantaneous. They have no duration. At once, they are blotted out and re-exist. But now they have changed their vibratory combinations. They exist a trifle differently—and the Time-scroll passes them along to the new position. On a motion picture film you would call it the next frame, or still picture. In radio you would say it has a trifle different tuning. Thus we have a pseudo-movement—Events. And we say that Time—the Time-scroll—keeps them separate. It is we who change—who seem to move, shoved along so that always we are compatible with Time.

nd thus is Time-traveling possible. With a realization of what I have here summarized, Harl and the cripple Tugh made an exhaustive study of the vibratory factors by which Matter is built up into form, and seeming solidity. They found what might be termed the Basic Vibratory Factor—the sum of all the myriad tiny movements. They found this Basic Factor identical for all the material bodies when judged simultaneously. But, every instant, the Factor was slightly changed. This was the natural change, mov[228]ing us a little upon the Time-scroll.

They delved deeper, until, with all the scientific knowledge of their age, they were able with complicated electronic currents to alter the Basic Vibratory Factors; to tune, let us say, a fragment or something to a different etheric wave-length.

They did that with a small material particle—a cube of metal. It became wholly incompatible with its Present place on the Time-scroll, and whisked away to another place where it was compatible. To Harl and Tugh, it vanished. Into their Past, or their Future: they did not know which.

I set down merely the crudest fundamentals of theory in order to avoid the confusion of technicalities. The Time-traveling cages, intricate in practical working mechanisms beyond the understanding of any human mind of my Time-world, nevertheless were built from this simple theory. And we who used them did but find that the Creator had given us a wider part to play; our pictures, our little niches were engraven upon the scroll over wider reaches.

gain to consider practicality, I asked Tina what would happen if I were to travel to New York City around 1920. I was a boy, then. Could I not leave the cage and do things in 1920 at the same time in my boyhood I was doing other things? It would be a condition unthinkable.

But there, beyond all calculation of Science, the all-wise Omnipotence forbids. One may not appear twice in simultaneity upon the Time-scroll. It is an eternal, irrevocable record. Things done cannot be undone.

"But," I persisted, "suppose we tried to stop the cage?"

"It would not stop," said Tina. "Nor can we see through its windows events in which we are actors."

One may not look into the future! Through all the ages, necromancers have tried to do that but wisely it is forbidden. And I can recall, and so can Larry, as we traveled through Time, the queer blank spaces which marked forbidden areas.

Strangely wonderful, this vast record on the scroll of Time! Strangely beautiful, the hidden purposes of the Creator! Not to be questioned are His purposes. Each of us doing our best; struggling with our limitations; finding beauty because we have ugliness with which to compare it; realizing, every one of us—savage or civilised, in every age and every condition of knowledge—realizing with implanted consciousness the existence of a gentle, beneficent, guiding Divinity. And each of us striving always upward toward the goal of Eternal Happiness.

To me it seems singularly beautiful.

CHAPTER XI Back to the Beginning of Time

s Mary Atwood and I sat chained to the floor of the Time-cage, with Migul the Robot guarding us, I felt that we could not escape. This mechanical thing which had captured us seemed inexorable, utterly beyond human frailty. I could think of no way of surprising it, or tricking it.

The Robot said. "Soon we will be there in 1777. And then there is that I will be forced to do.

"We are being followed," it added. "Did you know that?"

"No," I said. Followed? What could that mean?

There was a device upon the table. I have already described a similar one, the Time-telespectroscope. At this—I cannot say Time: rather must I invent a term—exact instant of human consciousness. Larry, Tina and Harl were gazing at their telespectroscopes, following us.[229]

The Robot said. "Enemies follow us. But I will escape them. I shall go to the Beginning, and shake them off."

Rational, scheming thought. And I could fancy that upon its frozen corrugated forehead there was a frown of annoyance. Its hand gesture was so human! So expressive!

It said. "I forget. I must make several quick trips from 2930 to 1935. My comrades must be transported. It requires careful calculation, so that very little Time is lost to us."

"Why?" I demanded. "What for?"

It seemed lost in a reverie.

I said sharply, "Migul!"

Instantly it turned. "What?"

"I asked you why you are transporting your comrades to 1935."

"I did not answer because I did not wish to answer," it said.

Again came the passage of Time.

think that I need only sketch the succeeding incidents, since already I have described them from the viewpoint of Larry, in 1777, and Dr. Alten, in 1935. It was Mary's idea to write the note to her father, which the British redcoats found in Major Atwood's garden. I had a scrap of paper and a fountain pen in my pocket. She scribbled it while Migul was intent upon stopping us at the night and hour he wished. It was her good-by to her father, which he was destined not to see. But it served a purpose which we could not have guessed: it reached Larry and Tina.

The vehicle stopped with a soundless clap. When our senses cleared we became aware that Migul had the door open.

Darkness and a soft gentle breeze were outside.

Migul turned with a hollow whisper. "If you make a sound I will kill you."

A moment's pause, and then we heard a man's startled voice. Major Atwood had seen the apparition. I squeezed the paper into a ball and tossed it through the bars, but I could see nothing of what was happening outside. There seemed a radiance of red glow. Whether Mary and I would have tried to shout and warn her father I do not know. We heard his voice only a moment. Before we realized that he had been assailed. Migul came striding back; and outside, from the nearby house a negress was screaming. Migul flung the door closed, and we sped away.

The cage which had been chasing us seemed no longer following. From 1777, we turned forward toward 1935 again. We flashed past Larry, Tina and Harl who were arriving at 1777 in pursuit of us. I think that Migul saw their cage go past; but Larry afterward told me that they did not notice our swift passing, for they were absorbed in landing.

eginning then, we made a score or more passages from 1935 to 2930. And we made them in what, to our consciousness, might have been the passing of a night. Certainly it was no longer than that.[1]

[1] At the risk of repetition I must make the following clear: Time-traveling only consumes Time in the sense of the perception of human consciousness that the trip has duration. The vehicles thus moved "fast" or "slow" according to the rate of change which the controls of the cage gave its inherent vibration factors. Too sudden a change could not be withstood by the human passengers. Hence the trips—for them—had duration.

Migul took Mary and me from 1935 to 1777. The flight seems perhaps half an hour. At a greater rate of vibration change, we sped to 2930; and back and forth from 2930 to 1935. At each successive arrival in 1935, Migul so skilfully calculated the stop that it occurred upon the same night, at the same hour, and only a minute or so later. And in 2930 he achieved the same result. To one who might stand at either end and watch the cage depart, the round trip was made in three or four minutes at most.[230]

We saw, at the stop in 2930, only a dim blue radiance outside. There was the smell of chemicals in the air, and the faint, blended hum and clank of a myriad machines.

They were weird trips. The Robots came tramping in, and packed themselves upright, solidly, around us. Yet none touched us as we crouched together. Nor did they more than glance at us.

Strange passengers! During the trips they stood unmoving. They were as still and silent as metal statues, as though the trip had no duration. It seemed to Mary and me, with them thronged around us, that in the silence we could hear the ticking, like steady heart-beats, of the mechanisms within them....

In the backyard of the house on Patton Place—it will be recalled that Migul chose about 9 P. M. of the evening of June 9—the silent Robots stalked through the doorway. We flashed ahead in Time again; reloaded the cage; came back. Two or three trips were made with inert mechanical things which the Robots used in their attack on the city of New York. I recall the giant projector which brought the blizzard upon the city. It, and the three Robots operating it, occupied the entire cage for a passage.

At the end of the last trip, one Robot, fashioned much like Migul though not so tall, lingered in the doorway.

"Make no error, Migul," it said.

"No; do not fear. I deliver now, at the designated day, these captives. And then I return for you."

"Near dawn."

"Yes; near dawn. The third dawn; the register to say June 12, 1935. Do your work well."

We heard what seemed a chuckle from the departing Robot.

Alone again with Migul we sped back into Time.

Abruptly I was aware that the other cage was after us again! Migul tried to elude it, to shake it off. But he had less success than formerly. It seemed to cling. We sped in the retrograde, constantly accelerating back to the Beginning. Then came a retardation, for a swift turn. In the haze and murk of the Beginning, Migul told us he could elude the pursuing cage.

igul, let us come to the window," I asked at last.

The Robot swung around. "You wish it very much, George Rankin?"

"Yes."

"There is no harm, I think. You and this girl have caused me no trouble. That is unusual from a human."

"Let us loose. We've been chained here long enough. Let us stand by the window with you," I repeated.

We

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)