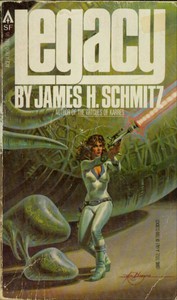

Legacy by James H. Schmitz (graded readers txt) 📖

- Author: James H. Schmitz

Book online «Legacy by James H. Schmitz (graded readers txt) 📖». Author James H. Schmitz

Trigger lay down on the couch. She had a very brief sensation of falling gently through dimness.

Half an hour later she sat up on the couch. Pilch switched on a desk light and looked at her thoughtfully. Trigger blinked. Then her eyes widened, first with surprise, then in comprehension.

"Liar!" she said.

"Hm-m-m," said Pilch. "Yes."

"That was the interview!"

"True."

"Then you're the egghead!"

"Tcha!" said Pilch. "Well, I believe I can modestly describe myself as being like that. Yes. You're another, by the way. We're just smart about different things. Not so very different."

"You were smart about this," Trigger said. She swung her legs off the couch and regarded Pilch dubiously. Pilch grinned.

"Took most of the disagreeableness out of it, didn't it?"

"Yes," Trigger admitted, "it did. Now what do we do?"

"Now," said Pilch, "I'll explain."

The thing that had caught their attention was a quite simple process. It just happened to be a process the Psychology Service hadn't observed under those particular circumstances before.

"Here's what our investigators had the last time," Pilch said. "Lines and lines of stuff, of course. But here's a simple continuity which makes it clear. Your mother dies when you're six months old. Then there are a few nurses whom you don't like very much. Good nurses but frankly much too stupid for you, though you don't know that, and they don't either, naturally. Next, you're seven years old—a bit over—and there's a mud pond on the farm near Ceyce where you spend all your vacations. You just love that old mud pond."

Trigger laughed. "A smelly old hole, actually! Full of froggy sorts of things. I went out to that farm six years ago, just to look around it again. But you're right. I did love that mud pond, once."

"Right up to that seventh summer," Pilch said. "Which was the summer your father's cousin spent her vacation on the farm with you."

Trigger nodded. "Perhaps. I don't remember the time too well."

"Well," Pilch said, "she was a brilliant woman. In some ways. She was about the age your mother had been when she died. She was very good-looking. And she was nice! She played games with a little girl, sang to her. Told her stories. Cuddled her."

Trigger blinked. "Did she? I don't—"

"However," said Pilch, "she did not play games with, tell stories to, cuddle, etcetera, little girls who"—her voice went suddenly thin and edged—"come in all filthy and smelling from that dirty, slimy old mud pond!"

Trigger looked startled. "You know," she said, "I do believe I remember her saying that—just that way!"

"You remember it," said Pilch, "now. You never saw her again after that summer. Your father had good sense. He didn't marry her, as he apparently intended to do before he saw how she was going to be with you. You went back to your old mud pond just once more, on your next vacation. She wasn't there. What had you done? You waded around, feeling pretty sad. And you stepped on a sharp stick and cut your foot badly. Sort of a self-punishment."

She flipped over a few pages of some record on her desk. "Now before you start asking what's interesting about that, I'll run over a few crossed-in items. Age twelve. There's that Maccadon animal like a dryland jellyfish—a mingo, isn't it?—that swallowed your kitten."

"The mingo!" Trigger said. "I remember that. I killed it."

"Right. You kicked it apart and pulled out the kitten, but the kitten was dead and partly digested. You bawled all day and half the night about that."

"I might have, I suppose."

"You did. Now those are two centering points. There's other stuff connected with them. No need to go into details. As classes—you've stepped now and then on things that squirmed or squashed. Bad smells. Etcetera. How do you feel about plasmoids?"

Trigger wrinkled her nose. "I just think they're unpleasant things. All except—"

Oops! She checked herself.

"—Repulsive," said Pilch. "It's quite all right about Repulsive. We've been informed of that supersecret little item you're guarding. If we hadn't been told, we'd know now, of course. Go ahead."

"Well, it's odd!" Trigger remarked thoughtfully. "I just said I thought plasmoids were rather unpleasant. But that's the way I used to feel about them. I don't feel that way now."

"Except again," said Pilch, "for that little monstrosity on the ship. If it was a plasmoid. You rather suspect it was, don't you?"

Trigger nodded. "That would be pretty bad!"

"Very bad," said Pilch. "Plasmoids generally, you feel about them now as you feel about potatoes ... rocks ... neutral things like that?"

"That's about it," Trigger said. She still looked puzzled.

"We'll go over what seems to have changed your attitude there in a minute or so. Here's another thing—" Pilch paused a moment, then said, "Night before last, about an hour after you'd gone to bed, you had a very light touch of the same pattern of mental blankness you experienced on that plasmoid station."

"While I was asleep?" Trigger said, startled.

"That's right. Comparatively very light, very brief. Five or six minutes. Dream activity, etcetera, smooths out. Some blocking on various sense lines. Then, normal sleep until about five minutes before you woke up. At that point there may have been another minute touch of the same pattern. Too brief to be actually definable. A few seconds at most. The point is that this is a continuing process."

She looked at Trigger a moment. "Not particularly alarmed, are you?"

"No," said Trigger. "It just seems very odd." She added, "I got rather frightened when Commissioner Tate was first telling me what had been going on."

"Yes, I know."

Pilch was silent for some moments again, considering the wall-screen as if thinking about something connected with it. "Well, we'll drop that for now," she said finally. "Let me tell you what's been happening these months, starting with that first amnesia-covered blankout on Harvest Moon. The Maccadon Colonial School has sound basic psychology courses, so there won't be much explaining to do. The connection between those incidents I mentioned and your earlier feeling of disliking plasmoids is obvious, isn't it?"

Trigger nodded.

"Good. When you got the first Service check-up at Commissioner Tate's demand, there was very little to go on. The amnesia didn't lift immediately—not very unusual. The blankout might be interesting because of the circumstances. Otherwise the check showed you were in a good deal better than normal condition. Outside of total therapy processes—and I believe you know that's a long haul—there wasn't much to be done for you, and no particular reason to do it. So an amnesia-resolving process was initiated and you were left alone for a while.

"Actually something already was going on at the time, but it wasn't spotted until your next check. What it's amounted to has been a relatively minor but extremely precise and apparently purposeful therapy process. Your unconscious memories of those groupings of incidents I was talking about, along with various linked groupings, have gradually been cleared up. Emotion has been drained away, fixed evaluations have faded. Associative lines have shifted.

"Now that's nothing remarkable in itself. Any good therapist could have done the same for you, and much more rapidly. Say in a few hours' hard work, spread over several weeks to permit progressive assimilation without conscious disturbances. The very interesting thing is that this orderly little process appears to have been going on all by itself. And that just doesn't happen. You disturbed now?"

Trigger nodded. "A little. Mainly I'm wondering why somebody wants me to not-dislike plasmoids."

"So am I wondering," said Pilch. "Somebody does, obviously. And a very slick somebody it is. We'll find out by and by. Incidentally, this particular part of the business has been concluded. Apparently, somebody doesn't intend to make you wild for plasmoids. It's enough that you don't dislike them."

Trigger smiled. "I can't see anyone making me wild for the things, whatever they tried!"

Pilch nodded. "Could be done," she said. "Rather easily. You'd be bats, of course. But that's very different from a simple neutralizing process like the one we've been discussing.... Now here's something else. You were pretty unhappy about this business for a while. That wasn't somebody's fault. That was us. I'll explain.

"Your investigators could have interfered with the little therapy process in a number of ways. That wouldn't have taught them a thing, so they didn't. But on your third check they found something else. Again it wasn't in the least obtrusive; in someone else they mightn't have given it a second look. But it didn't fit at all with your major personality patterns. You wanted to stay where you were."

"Stay where I was?"

"In the Manon System."

"Oh!" Trigger flushed a little. "Well—"

"I know. Let's go on a moment. We had this inharmonious inclination. So we told Commissioner Tate to bring you to the Hub and keep you there, to see what would happen. And on Maccadon, in just a few weeks, you'd begun working that moderate inclination to be back in the Manon System up to a dandy first-rate compulsion."

Trigger licked her lips. "I—"

"Sure," said Pilch. "You had to have a good sensible reason. You gave yourself one."

"Well!"

"Oh, you were fond of that young man, all right. Who wouldn't be? Wonderful-looking lug. I'd go for him myself—till I got him on that couch, that is. But that was the first time you hadn't been able to stand a couple of months away from him. It was also the first time you'd started worrying about competition. You now had your justification. And we," Pilch said darkly, "had a fine, solid compulsion with no doubt very revealing ramifications to it to work on. Just one thing went wrong with that, Trigger. You don't have the compulsion any more."

"Oh?"

"You don't even," said Pilch, "have the original moderate inclination. Now one might have some suspicions there! But we'll let them ride for the moment."

She did something on the desk. The huge wall-screen suddenly lit up. A soft, amber-glowing plane of blankness, with a suggestion of receding depths within it.

"Last night, shortly before you woke up," Pilch said, "you had a dream. Actually you had a series of eight dreams during the night which seem pertinent here. But the earlier ones were rather vague preliminary structures. In one way and another, their content is included in this final symbol grouping. Let's see what we can make of them."

A shape appeared on the screen.

Trigger started, then laughed.

"What do you think of it?" Pilch asked.

"A little green man!" she said. "Well, it could be a sort of counterpart to the little yellow thing on the ship, couldn't it? The good little dwarf and the very bad little dwarf."

"Could be," said Pilch. "How do you feel about the notion?"

"Good plasmoids and bad plasmoids?" Trigger shook her head. "No. It doesn't feel right."

"What else feels right?" Pilch asked.

"The farmer. The little old man who owned the farm where the mud pond was."

"Liked him, didn't you?"

"Very much! He knew a lot of fascinating things." She laughed again. "You know, I'd hate to have him find out—but that little green man also reminds me quite a bit of Commissioner Tate."

"I don't think he'd mind hearing it," Pilch said. She paused a moment. "All right—what's this?"

A second shape appeared.

"A sort of caricature of a wild, mean horse," Trigger said. She added thoughtfully, "there was a horse like that on that farm, too. I suppose you know that?"

"Yes. Any thoughts about it?"

"No-o-o. Well, one. The little farmer was the only one who could handle that horse. It was mutated horse, actually—one of the Life Bank deals that didn't work out so well. Enormously strong. It could work forty-eight hours at a stretch without even noticing it. But it was just a plain mean animal."

"'Crazy-mean,'" observed Pilch, "was the dream feeling about it."

Trigger nodded. "I remember I used to think it was crazy for that horse to want to go around kicking and biting things to pieces. Which was about all it really wanted to do. I imagine it was crazy, at that."

"You weren't ever in any danger from it yourself, were you?"

Trigger laughed. "I couldn't have got anywhere near it! You should have seen the kind of place the old farmer kept it when it wasn't working."

"I did," said Pilch. "Long, wide, straight-walled pit in the ground. Cover for shade, plenty of food, running water. He was a good farmer. Very high locked fence around it to keep little girls and anyone else from getting too close to his useful monster."

"Right," said Trigger. She shook her head. "When you people look into somebody's mind, you look!"

"We work at it," Pilch said. "Let's see what you can do with this one."

Trigger was silent for almost a minute before she said in a subdued voice, "I just get what it shows. It doesn't seem to mean anything?"

"What does it show?"

"Laughing giants stamping on a farm. A tiny sort of farm. It looks like it might be the little green man's farm. No, wait. It's not his! But it belongs to other little green people."

"How do you feel about that?"

"Well—I hate those giants!" Trigger

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)