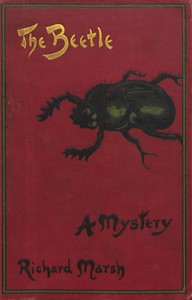

The Beetle: A Mystery by Richard Marsh (romantic love story reading .txt) 📖

- Author: Richard Marsh

Book online «The Beetle: A Mystery by Richard Marsh (romantic love story reading .txt) 📖». Author Richard Marsh

‘And what does all the world know of him?—I ask you that! A flashy, plausible, shallow-pated, carpet-bagger,—that is what all the world knows of him. The man’s a political adventurer,—he snatches a precarious, and criminal, notoriety, by trading on the follies of his fellow-countrymen. He is devoid of decency, destitute of principle, and impervious to all the feelings of a gentleman. What do you know of him besides this?’

‘I am not prepared to admit that I do know that.’

‘Oh yes you do!—don’t talk nonsense!—you choose to screen the fellow! I say what I mean,—I always have said, and I always shall say.—What do you know of him outside politics,—of his family—of his private life?’

‘Well,—not very much.’

‘Of course you don’t!—nor does anybody else! The man’s a mushroom,—or a toadstool, rather!—sprung up in the course of a single night, apparently out of some dirty ditch.—Why, sir, not only is he without ordinary intelligence, he is even without a Brummagen substitute for manners.’

He had worked himself into a state of heat in which his countenance presented a not too agreeable assortment of scarlets and purples. He flung himself into a chair, threw his coat wide open, and his arms too, and started off again.

‘The family of the Lindons is, at this moment, represented by a—a young woman,—by my daughter, sir. She represents me, and it’s her duty to represent me adequately—adequately, sir! And what’s more, between ourselves, sir, it’s her duty to marry. My property’s my own, and I wouldn’t have it pass to either of my confounded brothers on any account. They’re next door to fools, and—and they don’t represent me in any possible sense of the word. My daughter, sir, can marry whom she pleases,—whom she pleases! There’s no one in England, peer or commoner, who would not esteem it an honour to have her for his wife—I’ve told her so,—yes, sir, I’ve told her, though you—you’d think that she, of all people in the world, wouldn’t require telling. Yet what do you think she does? She—she actually carries on what I—I can’t help calling a—a compromising acquaintance with this man Lessingham!’

‘No!’

‘But I say yes!—and I wish to heaven I didn’t. I—I’ve warned her against the scoundrel more than once; I—I’ve told her to cut him dead. And yet, as—as you saw yourself, last night, in—in the face of the assembled House of Commons, after that twaddling clap-trap speech of his, in which there was not one sound sentiment, nor an idea which—which would hold water, she positively went away with him, in—in the most ostentatious and—and disgraceful fashion, on—on his arm, and—and actually snubbed her father.—It is monstrous that a parent—a father!—should be subjected to such treatment by his child.’

The poor old boy polished his brow with his pocket-handkerchief.

‘When I got home I—I told her what I thought of her, I promise you that,—and I told her what I thought of him,—I didn’t mince my words with her. There are occasions when plain speaking is demanded,—and that was one. I positively forbade her to speak to the fellow again, or to recognise him if she met him in the street. I pointed out to her, with perfect candour, that the fellow was an infernal scoundrel,—that and nothing else!—and that he would bring disgrace on whoever came into contact with him, even with the end of a barge pole.—And what do you think she said?’

‘She promised to obey you, I make no doubt.’

‘Did she, sir!—By gad, did she!—That shows how much you know her!—She said, and, by gad, by her manner, and—and the way she went on, you’d—you’d have thought that she was the parent and I was the child—she said that I—I grieved her, that she was disappointed in me, that times have changed,—yes, sir, she said that times have changed!—that, nowadays, parents weren’t Russian autocrats—no, sir, not Russian autocrats!—that—that she was sorry she couldn’t oblige me,—yes, sir, that was how she put it,—she was sorry she couldn’t oblige me, but it was altogether out of the question to suppose that she could put a period to a friendship which she valued, simply on account of—of my unreasonable prejudices,—and—and—and, in short, she—she told me to go the devil, sir!’

‘And did you—’

I was on the point of asking him if he went,—but I checked myself in time.

‘Let us look at the matter as men of the world. What do you know against Lessingham, apart from his politics?’

‘That’s just it,—I know nothing.’

‘In a sense, isn’t that in his favour?’

‘I don’t see how you make that out. I—I don’t mind telling you that I—I’ve had inquiries made. He’s not been in the House six years—this is his second Parliament—he’s jumped up like a Jack-in-the-box. His first constituency was Harwich—they’ve got him still, and much good may he do ’em!—but how he came to stand for the place,—or who, or what, or where he was before he stood for the place, no one seems to have the faintest notion.’

‘Hasn’t he been a great traveller?’

‘I never heard of it.’

‘Not in the East?’

‘Has he told you so?’

‘No,—I was only wondering. Well, it seems to me that to find out that nothing is known against him is something in his favour!’

‘My dear Sydney, don’t talk nonsense. What it proves is simply,—that he’s a nothing and a nobody. Had he been anything or anyone, something would have been known about him, either for or against. I don’t want my daughter to marry a man who—who—who’s shot up through a trap, simply because nothing is known against him. Ha-hang me, if I wouldn’t ten times sooner she should marry you.’

When he said that, my heart leaped in my bosom. I had to turn away.

‘I am afraid that is out of the question.’

He stopped in his tramping, and looked at me askance.

‘Why?’

I felt that, if I was not careful, I should be done for,—and, probably, in his present mood, Marjorie too.

‘My dear Lindon, I cannot tell you how grateful I am to you for your suggestion, but I can only repeat that—unfortunately, anything of the kind is out of the question.’

‘I don’t see why.’

‘Perhaps not.’

‘You—you’re a pretty lot, upon my word!’

‘I’m afraid we are.’

‘I—I want you to tell her that Lessingham is a damned scoundrel.’

‘I see.—But I would suggest that if I am to use the influence with which you credit me to the best advantage, or to preserve a shred of it, I had hardly better state the fact quite so bluntly as that.’

‘I don’t care how you state it,—state it as you like. Only—only I want you to soak her mind with a loathing of the fellow; I—I—I want you to paint him in his true colours; in—in—in fact, I—I want you to choke him off.’

While he still struggled with his words, and with the perspiration on his brow, Edwards entered. I turned to him.

‘What is it?’

‘Miss Lindon, sir, wishes to see you particularly, and at once.’

At that moment I found the announcement a trifle perplexing,—it delighted Lindon. He began to stutter and to stammer.

‘T-the very thing!—c-couldn’t have been better!—show her in here! H-hide me somewhere,—I don’t care where,—behind that screen! Y-you use your influence with her;—g-give her a good talking to;—t-tell her what I’ve told you; and at—at the critical moment I’ll come in, and then—then if we can’t manage her between us, it’ll be a wonder.’

The proposition staggered me.

‘But, my dear Mr Lindon, I fear that I cannot—’

He cut me short.

‘Here she comes!’

Ere I could stop him he was behind the screen,—I had not seen him move with such agility before!—and before I could expostulate Marjorie was in the room. Something which was in her bearing, in her face, in her eyes, quickened the beating of my pulses,—she looked as if something had come into her life, and taken the joy clean out of it.

CHAPTER XXI.THE TERROR IN THE NIGHT

‘Sydney!’ she cried, ‘I’m so glad that I can see you!’

She might be,—but, at that moment, I could scarcely assert that I was a sharer of her joy.

‘I told you that if trouble overtook me I should come to you, and—I’m in trouble now. Such strange trouble.’

So was I,—and in perplexity as well. An idea occurred to me,—I would outwit her eavesdropping father.

‘Come with me into the house,—tell me all about it there.’

She refused to budge.

‘No,—I will tell you all about it here.’ She looked about her,—as it struck me queerly. ‘This is just the sort of place in which to unfold a tale like mine. It looks uncanny.’

‘But—’

‘“But me no buts!” Sydney, don’t torture me,—let me stop here where I am,—don’t you see I’m haunted?’

She had seated herself. Now she stood up, holding her hands out in front of her in a state of extraordinary agitation, her manner as wild as her words.

‘Why are you staring at me like that? Do you think I’m mad?—I wonder if I’m going mad.—Sydney, do people suddenly go mad? You’re a bit of everything, you’re a bit of a doctor too, feel my pulse,—there it is!—tell me if I’m ill!’

I felt her pulse,—it did not need its swift beating to inform me that fever of some sort was in her veins. I gave her something in a glass. She held it up to the level of her eyes.

‘What’s this?’

‘It’s a decoction of my own. You might not think it, but my brain sometimes gets into a whirl. I use it as a sedative. It will do you good.’

She drained the glass.

‘It’s done me good already,—I believe it has; that’s being something like a doctor.—Well, Sydney, the storm has almost burst. Last night papa forbade me to speak to Paul Lessingham—by way of a prelude.’

‘Exactly. Mr Lindon—’

‘Yes, Mr Lindon,—that’s papa. I fancy we almost quarrelled. I know papa said some surprising things,—but it’s a way he has,—he’s apt to say surprising things. He’s the best father in the world, but—it’s not in his nature to like a really clever person; your good high dried old Tory never can;—I’ve always thought that that’s why he’s so fond of you.’

‘Thank you, I presume that is the reason, though it had not occurred to me before.’

Since her entry, I had, to the best of my ability, been turning the position over in my mind. I came to the conclusion that, all things considered, her father had probably as much right to be a sharer of his daughter’s confidence as I had, even from the vantage of the screen,—and that for him to hear a few home truths proceeding from her lips might serve to clear the air. From such a clearance the lady would not be likely to come off worst. I had not the faintest inkling of what was the actual purport of her visit.

She started off, as it seemed to me, at a tangent.

‘Did I tell you last night about what took place yesterday morning,—about the adventure of my finding the man?’

‘Not a word.’

‘I believe I meant to,—I’m half disposed to think he’s brought me trouble. Isn’t there some superstition about evil befalling whoever shelters a homeless stranger?’

‘We’ll hope not, for humanity’s sake.’

‘I fancy there is,—I feel sure there is.—Anyhow, listen to my story. Yesterday morning, before breakfast,—to be accurate, between eight and nine, I looked out of the window, and I saw a crowd in the street. I sent Peter out to see what was the matter. He came back and said there was a man in a fit. I went out to look at the man in the fit. I found, lying on the ground, in the centre of the crowd, a man who, but for the tattered remnants of what had apparently once been a cloak, would have been stark naked. He was covered with dust, and dirt, and blood,—a dreadful sight. As you know, I have had my smattering of instruction in First Aid to the Injured, and that kind of thing, so, as no one else seemed to have any sense, and the man seemed as good as dead, I thought I would try my hand. Directly I knelt down beside him, what do you think he said?’

I WENT OUT TO LOOK AT THE MAN.

‘Thank you.’

‘Nonsense.—He said, in such a queer, hollow, croaking voice, “Paul Lessingham.” I was dreadfully startled. To hear a perfect stranger, a man in his condition, utter that name in such a fashion—to me, of all people in the world!—took me aback. The policeman who was holding his head remarked, “That’s the first time he’s opened his mouth. I thought he was dead.” He opened his mouth a second time. A convulsive movement went all over him, and he exclaimed, with the strangest earnestness, and so loudly that you might have heard him at the other end of the street, “Be warned, Paul Lessingham, be warned!” It was very silly of me, perhaps, but I cannot tell

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)