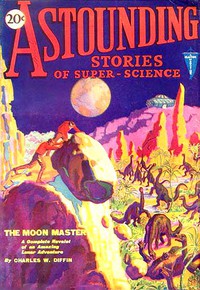

Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 by Various (red queen ebook TXT) 📖

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 by Various (red queen ebook TXT) 📖». Author Various

Fully fifteen miles in diameter, it was a huge doughnut, a great ring of tubing with a center-opening that was at least eighty per cent of its maximum diameter. There it hovered, sending out those deadly missiles in a continuous stream toward our poor world. As we approached the weird space flier, we saw that a number of objects floated about within the great circle of its inner circumference. The NY-18, the SF-61 and the SF-22, without doubt! The theory of Hart's was correct in every detail.

We were still at about ten miles distance from the great ring and the streaking light pencils were speeding earthward at the rate of one a minute now. There was no time to lose. Already there was more destruction on its way than had been previously wrought—several times over.

Hart was sighting along a tiny tube that projected into the forward partition and he maneuvered the Pioneer until she was nose on to the great ring. He pulled a switch and there came a purring that was entirely new. A row of huge vacuum tubes along the wall lighted to vivid brilliancy and a throbbing vibration filled the artificial air of the cabin.

He pulled a small lever at the side of the tube and the vessel rocked to the energy that was released from those vacuum tubes. The thin rod which had been installed at the Pioneer's nose burst into brilliant flame—orange tinted luminescence that grew to a sphere of probably ten feet in diameter. Then there was a heavy shock and the ball of fire left its position and, with inconceivable velocity, sprang straight for the side of the great ring. It was a fair hit and, when the weird missile found its mark, it simply vanished—swallowed up in the metal walls of the monster vessel. For a moment we thought nothing was to result. Then we burst into shouts of joy, for a great section of the ring fused into nothingness and was gone! Fully a quarter of the circumference of the ring had disappeared into the vacuum of space. Truly, the governments of Earth had developed some terrible weapons of their own!

We watched, breathless.[Pg 79]

The green light pencils no longer streaked their paths of death in the direction of our world, which now seemed so remote. The great ring with the vacant space in its rim wabbled uncertainly for a moment as though some terrific upheaval from within was tearing it asunder. Then it lurched directly for the Pioneer. We had been observed!

But Hart was equal to the occasion and he shot the Pioneer in the direction of the earth with such acceleration that we all were flattened into our supports with the same old violence. Then, with equal violence, we decelerated. The ring was following so closely that it actually rushed many hundreds of miles past us before it was brought to rest. From it there sprang one of the light pencils, and the Pioneer was rocked as by a heavy gale when it rushed past on its harmless way into infinity. The enemy had missed.

Meanwhile, Hart was operating another mechanism that was new to the Pioneer and again he sighted along the tiny tube. This time there was no sound within, no ball of fire without, no visible ray. But, when he had pressed the release of this second energy, the ring seemed to shrivel and twist as if gripped by a giant's hand. It reeled and spun. Then, no longer in a balance of forces, it commenced its long drop earthward.

His job finished and finished well, Hart Jones collapsed.

Following his more than three days and four nights of superhuman endeavor, it seemed strange to see Hart slumped white and still over the control pedestal. He who had energy far in excess of that of any of the rest of us had worn himself out. Having had no rest or sleep in nearly a hundred hours, the body that housed so wonderful a spirit simply refused to carry on. Tenderly we stretched him on the cabin floor, the Pioneer drifting in space the while. The professor, who was likewise something of a physician, listened to his heart, drew back his eyelids, and pronounced him in no danger whatever.

We slapped his wrists, sprinkled his face and neck with cold water from the drinking supply, and were soon rewarded by his return to consciousness. He smiled weakly and fell sound asleep. No war in the universe could have wakened him then, so we lifted him to his feet—rather I should say, we guided his practically floating body—and strapped him in George's hammock, preparing for the homeward journey. Though dangling from the straps in a position that would be vertical were we on earth, he slept like a baby. George took the controls in Hart's place and the professor and I returned to our accustomed supports.

The return trip was considerably slower, as George did not wish to push the Pioneer to its limit as had been necessary when coming out to meet the enemy, nor was he able to keep control of the ship against a too-rapid acceleration. Consequently, the rate of acceleration was much lower and we were not nearly as uncomfortable as on the outgoing trip. Thus, nearly ten hours were required for the return. And Hart slept through it all.

In order to make best use of the small amount of fuel still in the cylinders, George circled the earth five times before we entered the upper limits of the atmosphere, the circles becoming of smaller diameter at each revolution and the speed of the ship proportionately reduced. An occasional discharge from one of the forward rocket tubes assisted materially in the deceleration, yet, when we slipped into level five, our speed was so great that the temperature of the cabin rose alarmingly, due to the friction of the air against the hull of the vessel. It was necessary to use the last remaining ounce of fuel to reduce the velocity to a safe value. A long glide to earth was then our only means of landing and, since we were over the[Pg 80] Gulf of Mexico at the time, we had no recourse other than landing in the State of Texas.

Passing over Galveston in level three, we found that the Humble oil fields and a great section of the surrounding country had been the center of one of the enemy bombardments. All was blackness and ruin for many miles between this point and Houston. At Houston Airport we landed, unheralded but welcome.

The lower levels were once more filled with traffic, and one of the southern route transcontinental liners had just made its stop at this point. The arrival of the Pioneer was thus witnessed by an unusually large crowd, and, when the news was spread to the city, their numbers increased with all the rapidity made possible by the various means of transportation from the city.

So it was that Hart Jones, after we finally succeeded in awakening him and getting him to his feet, was hailed by a veritable multitude as the greatest hero of all time. The demonstrations become so enthusiastic that police reserves, hastily summoned from the city, were helpless in their attempts to keep the crowd in order.

It was with greatest difficulty that Hart was finally extricated from the clutches of the mob and conveyed to the new Rice Hotel in Houston, where it was necessary to obtain medical attention for him immediately. He was in no condition at the time to receive the richly deserved plaudits of the multitude, and, truth to tell, we others from the Pioneer were in much the same shape.

To me that night will always be the most terrible of nightmares. My first thought was of my family and, when I had been assigned to a room, I immediately asked the switchboard operator for a long-distance connection to my home in Rutherford. There was complete silence for a minute and I jangled the hook impatiently, my head throbbing with a thousand aches and pains. Then, to my surprise, the voice of the hotel manager greeted me.

"Mr. Makely," he said softly, and I thought there was a peculiar ring in his voice, "I think you had better not try to get Rutherford this evening. We are sending the house physician to your room at once and—there are orders from Washington, you know—you are to think of nothing at the present but sleep and a long rest."

"Why—why—" I stammered, "can't you see? I must communicate with my family. They must know of my return. I must know if they're safe and well."

"I'm sorry, sir," apologized the manager, "Government orders, you know." And he hung up.

Something in that soft voice brought to me an inkling of the truth. An icy hand gripped my heart as I heard a knock at the door. With palsied fingers I turned the key and admitted the professor and a kindly-faced elderly gentleman with a small black bag. One look at the professor told me the truth. I seized his two arms in a grip that made him wince.

"Tell me! Tell me!" I demanded, "Has anything happened to my family?"

"Jack," said the professor slowly, "while we were out there watching Hart destroy the enemy vessel, Rutherford was destroyed!"

It must be that I frightened him by my answering stare, for he backed away from me in apparent fear. I noticed that the doctor was rummaging in his bag. I know I did not speak, did not cry out, for my tongue clove to the roof of my mouth. It seemed I must go mad. The professor still backed away from me; then, wiry little athlete that he was, he sprang directly for my knees in a beautiful football tackle. I remember that point clearly and how I admired his agility at the time. I remember the glint of a small instrument in the doctor's hand. Then all was blackness.[Pg 81]

Eight days later, they tell me it was, I returned to painful consciousness in a hospital bed. But let me skip the agony of mind I experienced then. Suffice it to say that, when I was able, I set forth for Washington. Hart Jones was there and he had sent for me. But I took little interest in the going; did not even bother to speculate as to the reason for his summons. I had devoured the news during my convalescence and now, more than two weeks after the destruction of the Terror, I knew the extent of the damage wrought upon our earth by those deadly green light pencils we had seen issuing from the huge ring up there in the skies. The horror of it all was fresh in my mind, but my own private horror overshadowed all.

I was glad that Hart had been so signally honored by the World Peace Board, that he was now the most famous and popular man in the entire world. He deserved it all and more. But what cared I—I who had done least of all to help in his great work—that the Terror had been found where it buried itself in the sand of the Sahara when falling to earth? What cared I that the discoveries made in the excavating of the huge metal ring were of inestimable value to science?

It gave me passing satisfaction to note that all of Hart Jones' theories were borne out by the discoveries; that Oradel and his minions were responsible for this terrible war; that the planet they aligned against us was Venus and that more than a hundred thousand of the Venerians had been carried in that weird engine of destruction which had been brought down by Hart.

It was interesting to read of the fall of that huge ring; how it was heated to incandescence when it entered our atmosphere at such tremendous velocity; of the tidal waves of concentric billows in the sand that led to its discovery by Egyptian Government planes. The broadcast descriptions and the television views of the stunted and twisted Venerians whose bodies were recovered from the partly consumed wreckage were interesting. But it all left me cold. I had no further interest in life. That the world had escaped an overwhelming disaster was clear, and it gave me a certain pleasure. But for me it might as well have been completely destroyed.

Nevertheless, I went to Washington. I felt somehow that I owed it to Hart

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)