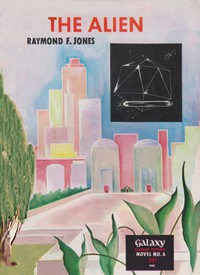

The Alien by Raymond F. Jones (best summer reads of all time TXT) 📖

- Author: Raymond F. Jones

Book online «The Alien by Raymond F. Jones (best summer reads of all time TXT) 📖». Author Raymond F. Jones

Illia sat in a corner of the room opposite him and her fists pressed white spots into her cheeks. Dreyer's nervous reaction was expressed in the incessant puffs and chewing on his normally steady cigar. The others merely watched with taut faces and teeth sinking into their lips.

In the chamber of the great museum palace, the tempo of the battle was slowly building up. Though he felt exhausted almost to the point of defeat, Underwood strained for more energy and found that it was at his command. His dor-abasa fed upon the attacking force of Demarzule and returned it with added energy potential.

In each of them, the same process was going on, and the outcome would be determined by the final resultant flow of destroying power.

He could retreat now, Underwood realized. He doubted that Demarzule could exert a holding force upon him, but nothing would be gained by abandoning the battle now. He drove on with increasing surges.

Suddenly there was a faltering and Underwood exulted within himself. Demarzule's force wavered for the barest fraction of an instant, and it was not a feint.

"You are old and weak," said Underwood. "Half a million years ago, civilization rejected you. We reject you!"

He smashed on almost without hindrance now. Demarzule's great form writhed in pain upon the throne—and fought with one desperate surge of energy.

Underwood caught and hurled it back mercilessly. He felt his way into the innermost recesses of the Sirenian mind, groped along the nerve ways of the Great One. And as he went, he burned and destroyed the vital synapses.

Demarzule was dying—slowly, because of his resistance—and in endless pain because there was no other way. He screamed aloud in ultimate agony, and then the giant figure of Demarzule, the Sirenian—the Great One—crashed to the floor.

The relief that came to Underwood was near agony. The wild forces of the Dragbora tore relentlessly from him and filled the room with their lethal energy before they died.

Then, in greater calm, he regarded what he had done. It was finished, almost unbelievably finished.

Yet there were a few things to do. He left the building and sought out the guards and the caretakers and whispered into their minds, "Demarzule is dead! The Great One has died and you are men once more."

He sought out the controls of the force shell and caused the operator to drop the shield. Then he whispered, "The Great One is dead," and like the wind, his voice encompassed the vast thousands who had gathered.

The message sank unspoken into their minds and each man looked at his neighbor as if to ask how it had come. They pressed forward, a battling, maddened mob who had for an hour lived in a childish, primitive world where men were not required to think but only to obey. They pushed forward and flowed into the building, battering, clawing one another. But they managed to view the body of the fallen Sirenian, so that the message was confirmed and spread, soon to circle the Earth.

Underwood studied the writhing, bewildered mass. Could Dreyer possibly be right? Would it ever end—men's unthinking grasping for leadership, their mindless search for kings and gods, while within them their own powers withered? Always it had been the same; leaders arose holding before men the illusion of vast, glorious promises while they carefully led them into hells of lost dreams and broken promises.

Yes, it would be different, Underwood told himself. The Dragbora had proved that it could be different. Their origin could have been no less lowly than man's. They must have trodden the same tortuous stairway to dreams that man was now on, and they had learned how to live with one another.

Man was already nearer that goal—far nearer now that Demarzule was dead. Underwood formed a silent prayer that fate would be merciful to man and not send another like Demarzule.

And he allowed himself a moment's pride, an instant of pleasure in the thought that he had been able to take part in the crisis.

With a final pity for the scene below, he fled back into space. What he saw there turned him sick with fear. The great fleet was broken and burned with atomic fires. Only two of the battleships remained to challenge the attackers. But they were no longer challenging. They signalled abject surrender and were fallen upon by ravenous interceptors.

The Lavoisier herself was darkened and drifting, her force shell feeble and waning, while the flaming disruptors of a trio of dreadnaughts concentrated upon her.

Underwood hurled himself toward the nearest of the enemy ships. In its depths he sought out the gunners and cut off life in them before they were aware of his bodiless presence. Swiftly he turned their beams upon each other and watched them wallow and disappear in sudden flame.

Others rushed forward now. Still more than a score of them to defeat the single crippled laboratory ship, more than he could hope to conquer in time.

But they did not fire. Their shields remained intact; then slowly their courses changed and they drifted away. Without comprehension, Underwood peered into those hulls and knew the answer.

The news had come to them of Demarzule's death. Like men in pursuit of a mirage, they could not endure the reality that came with the vanishing of their dream. Their defeat was utter and complete. Throughout the Earth Demarzule's defeat was the defeat of all men who had not yet become strong enough to walk in the sun of their own decisions, but clung to the shadow of illusory leadership.

Underwood swept back toward the darkened Lavoisier. He moved like a ghost through its bleak halls and vacant corridors. Down in the generator rooms, he found the cause of the disaster in the blasted remains of overburdened force shell generators. Four of them must have given way at once, ripping the ship throughout its length with concussion and lethal waves.

The control room was dark, like the rest of the ship, and the forms of his companions were strewn upon the floor. But there was life yet and he dared to hope as he spoke to their minds, insistent, commanding, forcing life and consciousness back into their nerve cells. He seemed to become aware of unknown powers of resurrection that dwelt within his own being.

His mission was complete. He returned to his own physical form and abandoned the abasic senses. He sat there in the huge chair in the control room, while those about him revived and life gradually returned to the dying ship. Of the enemy fleet there was no more, for it was descending to an Earth shorn of the hope of Galaxy-wide conquest.

They did not know yet where they would go or where they could find refuge, but when the wreckage was cleared and the ship lived again, Underwood and Illia stood alone in a darkened observation pit, watching the stars slip across the massive arc of the screens.

As Underwood watched, he thought he sensed something of the drive that might have whipped Demarzule's brain, the goad that made vast superior powers intolerable in the possession of even a beneficent man, for he would no longer remain beneficent.

By the might that was in him he had vanquished the Great One! He could stand in the place of the Great One if he chose! He did not know if his powers were becoming greater than those of Jandro, like a strengthened plant in new soil, but surely they were growing. The secrets of the Universe seemed to be appearing before him, one by one.

A mere glance at a slab of inert matter, and his senses could delve into the composition of its atoms and sort out and predict its properties and reactions. One look into the far spaces beyond the Solar System and he could sense himself soaring in eternity. Yes, he was growing in power and perception, and where it might lead, he dared not look.

But there were other things to be had, other, simpler ambitions in which common men had found fulfillment throughout the ages.

Illia was warm against him, soft in his arms.

"I want you to operate again, as quickly as possible," he said.

She looked up at him with a start. "What do you mean?"

"You must take out the abasic organs. They've served their purpose. I don't want to live with them. I could become another Demarzule with the power I have."

Her eyes were faintly blue in the light that came from the panel and they were intent upon him. In them he read something that made him afraid.

"There is always a need for men with greater powers and greater knowledge than the average man," she said. "The race has need of its mutants. They are dealt so sparingly to us that we cannot afford not to utilize them."

"Mutants?"

"You are a true mutant, whether artificial or not, possessing organs and abilities that are unique. The race needs them. You cannot ask me to destroy them."

He had never thought of himself as a mutant, yet she was right for all practical purposes. His powers and perceptions would perhaps not have been produced naturally in any man of his race for thousands of years to come. Perhaps he could use them to assist man's slow rise. A new wealth of science, a new strength of leadership and guidance if necessary—.

"I could become the world's greatest criminal," he said. "There's no secret, no property that's safe from my grasp. I have only to reach out for possessions, for power."

"You worry too much about that," she said lightly. "You could no more become a villain than I could."

"Why are you so sure of that?"

"Don't you remember the properties of the seaa-abasa? But then you didn't hear the last words that Jandro ever spoke, did you? He said, 'I retire to the seaa-abasa.' Do you know what that means?"

Suddenly, Underwood felt cold. A score of whisperings came thundering into his mind. The moment when he had first awakened from the operation, when it seemed as if death would have him and only the power of a demanding will had helped him cling to life. The voice that seemed to penetrate and call him back. The voice of Jandro. And then the final conflict in the chambers of Demarzule.

New skills and new strength had suddenly come to him as if out of nowhere. He had been conceited to call it his increased experience and ability. Yet could it have come from outside himself? He sought frantically and urgently within his own nerve channels, in the cells of his own being, and in the pathways of the alien organs that lent him those unearthly senses. There seemed nothing but an echo, as if within a great empty hall. There was no answer, yet it seemed as if down those channels of perception there was the dim shadow of a wary prey who could never be caught, who could never be found in those endless pathways, but who would never be far away.

Underwood knew then that if it was Jandro, he would never make himself known for reasons of his own, perhaps. But there was a sudden peace as if he had found some secret purification, as if he had been taken to a high place and looked about the world and had been able to turn his back upon it. Whether he would ever find Jandro or not, he was sure that the guardian was there.

Illia was saying, "I can't operate, Del. Even if you hate me for the rest of our lives, I won't do it. And there is no one else in the world who would know how. You would be killed if you let anyone else attempt to cut those nerves. Tell me that you believe I'm right."

"I do," he said in cheerful resignation. "But don't forget it's half your funeral as well. It means that you're going to have to spend the rest of your life with a mutant."

She turned her face up to his. "I can think of worse fates."

END

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of The Alien, by Raymond F. Jones Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)