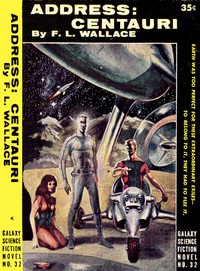

Address: Centauri by F. L. Wallace (most read book in the world .TXT) 📖

- Author: F. L. Wallace

Book online «Address: Centauri by F. L. Wallace (most read book in the world .TXT) 📖». Author F. L. Wallace

Anti left again, secure in the knowledge that he would do as he said. In his own way Docchi was as ruthless as Judd. But the purpose was different and therefore the comparison not accurate. Strength was not easy to define.

The librarian resembled an angular metallic squid spread out to dry on the floor. Docchi picked his way through the wiry tentacles, scrutinizing the work of the crew. He squatted near Webber, watching him splice and adjust the components, briefly giving advice and then moving on to the next man. The librarian was dormant but to Docchi's practiced eye it was nearly ready to be recalled to the semi-life of a memory machine.

Jordan came swinging in. Docchi heard him and turned. He knew who it was by the sound but seemed disappointed to find his judgment confirmed. "The star chart drum is finished," said Jordan, pausing at the tangle of wires. "Most of the observed data on the neighboring stars is included. Of course all the locations are figured from Earth."

"It's all right. The computers won't mind making the conversions." With his foot Docchi nudged a tool toward him that Webber was reaching for. "What about the crossover relays?"

"Done too, waiting to be tied in. Guaranteed to switch from one computer to the other before even they realize what's happening."

"Good. The next thing is the impulse recognition hunter. Last night I thought of a way to make the selection tighter. Here, I'll show you." Docchi went to a diagram strewn desk and waited while Jordan pawed through the sheets for him. "There it is," he said when Jordan uncovered it.

Jordan studied it in silence. "Can't make it," he said at last.

"Why not? It's not difficult."

"Yeah. But we can't manage the delivery from Earth. Don't have all the parts here." Jordan scratched his chest. "Tell you what. Think I can rob nonessential stuff and put together something like this." He took a pencil and began to sketch rapidly.

"It'll do," said Docchi, finally approving it after a number of changes.

Jordan scratched in the alterations. "Why so tight?" he complained, folding the sheet and tucking it away. "The computers don't have to be controlled so tight. They never have disobeyed."

"I know, and I'm not going to give them a chance. Every watt we allot must be used on the drive and for no other purpose."

Privately Jordan doubted it was necessary. When he thought of the great nuclear pile that warmed the heart of the asteroid and drove them on he didn't see how a mere ship, no matter how efficient, could surpass them. True, the ship was travelling faster now but that was because they weren't exerting their full energies. And when they did—Jordan shrugged and creased the paper again, swinging away.

At the door he swerved to miss Jeriann. "Hi," he said, hurrying a little faster. It was none of his concern what went on but he didn't have to be around when it blew up.

Jeriann returned the greeting and stood at the entrance. "May I come in?"

"Certainly. There's no sign it's restricted to electronic technicians."

Webber winked at her and bent his head over his work. Docchi was expressionless. "I want to talk to you," she said.

"About Maureen? I've heard. Go ahead."

She'd hoped he'd suggest a more private place but it was evident he didn't want to be alone with her. She didn't altogether blame him. "What I asked for the other day wasn't very realistic. It was mostly my fault. I had at least a month to think of getting a larger power supply to the machine but I thought I could get along without it. It was my own shortsightedness and I had no reason to expect you to drop what you're doing."

"You don't have to apologize. We're all trying to do our best—and various needs do conflict. Actually I might have found some way to run the extra power line if I hadn't been sure it was an act of pure desperation, that you had no idea of what you were going to do with it when you got it."

What made it worse was that he was right. The impulse had been irrational, the feeling that there must be something that would help. He should have said he was at fault too, that he should have built the command unit months ago. It made no difference he hadn't known there was a ship behind them. He should have said it.

"It's over," she said. "We've done what we could. I thought you'd like to see her while there's time."

"I can't leave for another ten hours. None of us can. We've got to get it wrapped up if it's going to be of any use at all," said Docchi, looking at what remained to be done. "Wait. You said I can see her. Sounds to me like she's better." He scanned her face hopefully.

She shook her head. "It doesn't mean that. We've stopped using hypnotics because they're no longer effective. Heavy sedatives, extremely heavy, are the only things that keep her from jumping up and running out to die."

His face was sallow. This was one of the times his slender shoulderless body seemed frailer than it was. "I'll come as soon as I can get away. We're near the finish line on this." He turned and walked past Webber to the far end of the room, bending over a technician's work to examine it.

She was trying to tell him and all he had to do was half listen. Nobody blamed either of them. Maureen wouldn't, if she were capable of any kind of judgment. From his position among the tangled tentacles of the mechanical squid, seemingly strangled by the motionless machinery, Webber winked soberly at her. Jeriann bit her lip and hurried out. Her eyes burned but that was all. Her body was protected against unnecessary fluid loss.

It wasn't possible to drive the technicians. They weren't very skilled and the work was delicate. From the beginning they had known the importance of what they were doing and they were already at their top speed and above that no increase in productivity could be achieved. When he said ten hours Docchi optimistically thought eighteen.

And yet they were done in nine. Not because it would help Maureen—they knew it wouldn't. But because—well, why? Nobody asked for explanations. They made no mistakes; nothing had to be torn down and built again. And the less skilled men, those who puttered from one instruction to the next, stalling between orders, now seemed to anticipate what they would be told and to complete the work before it was given to them. They learned fast and what they didn't know how to do was done right anyway.

The wires ceased to resemble tentacles and were neatly arranged in the cabinet of the command unit, formerly the librarian, which was then moved against the wall. Calling in Jordan and discussing it with him, Docchi left the remainder of the work in his capable hands.

He was tired all over, inside and out. He didn't want to see anyone die, not someone he had been partly responsible for sentencing, whatever the circumstances. He walked along in the semi-twilight, wishing there was a cool breeze. He hadn't ordered one and so it was missing. Before long there wouldn't be any power to spare for circulation of the air.

Anti met him at the hospital steps, going up with him. "I've been waiting. I didn't want to go in alone."

He talked to her briefly and they went on in silence. The asteroid was being diminished, perhaps already had been. They all had first hand knowledge of what death was—at one time or another they'd brushed very near to it—but they were not accustomed to losing the encounter. One of their own kind, who should live for hundreds of years, would not.

Jeriann heard them and came outside of the hushed room. "I don't know what to say," she whispered. "Oh yes I do. I wish I had your face, Docchi. You would see it shining."

Whatever she thought, her face was shining, though not in the same way. He looked into her eyes but they were not easy to read. "You did it," he whispered.

"I don't know why I'm talking so low," she said, raising her voice. "It doesn't hurt now. No, I didn't have anything to do with it. Come in and see her."

Maureen was sleeping. Her breathing was light but regular as the lung machines responded normally. Her skin was waxen but it was not unhealthy. The wrinkles of strain had fallen away and her face was relaxed in the beauty of survival.

"Go ahead and talk," said Cameron from the corner as he bent over an analyzer. "I shot her full of dope. I guess I didn't have to—she'll sleep now no matter what you do."

"Thanks, doctor," said Docchi. "We're lucky to have you."

"Not half as lucky as I am to be here. Damnedest thing I ever saw. My colleagues wouldn't believe it." Carefully he closed the analyzer and rolled it away. "I forget I no longer have colleagues."

"The more remarkable. Your efforts alone."

"I guess you don't understand. I had nothing to do with it," said Cameron. "I was an interested and awed spectator but nothing more. The person who saved Maureen was Maureen herself."

"Now how could she?" said Anti. "She lacked male hormones and the bodily processes were out of control, upset, running away with themselves." She raised a few inches from the floor to get a better glimpse of the patient. The best refutation of Anti's argument was Maureen herself.

"It couldn't happen to anyone but an accidental," began Jeriann, but Cameron cut her off.

His voice was cool and dry, that of a lecturer. It was the only chance he'd get to share his discovery. "You know why you're biocompensators: the severe injury, and later pulling through with the help of medical science, developing the extraordinary resistance I spoke of. You had to have it or you didn't live. And the resistance remained after the injury was gone.

"In Maureen's case every function began to be disturbed after the supply of hormones was cut off. It got worse as we were unable to manufacture what she needed. She developed a raging fever and was in a constant state of hallucination. In an earlier era she would have been a mass of cancerous tissue. Fortunately we are now able to control cancer quite simply.

"At any rate she was rapidly reaching the state where there was no coordination at all. Death should have been the result—but the body stepped in."

"Yes, but how?" said Anti.

"I don't know but I'm going to find out," said Cameron. "Last time I tested all the normal hormones were present. Somehow, out of tissues that weren't adapted to it, her body built up new organs and glands that supply her with the substances she needs to live."

Cell by cell the body had refused to die. Organs and nerves and tissues had fought the enveloping chaos. The body as a whole and in parts tried to survive but it was not adapted to conditions. So it adapted.

Nerves forged new paths in places they had never gone before because there was nothing at the end which they could attach to. But by the time they arrived at their destination certain specialized cells had changed their specialty. All cells in the adult body derived from an original one and they remembered though it was long ago. In the endless cellular generations since conception, in the continual microscopic death and rebirth that constitutes the life process, the cells had changed much—but in extremity the change was not irreversible.

Here a nerve began to fatten its stringy length; it was the beginning of what was later to become a long missing gland. Elsewhere a muscle seemed to encyst, adhering to another stray cell, changing both of them, working toward the definite goal.

From the brink the body turned and began the slow march toward health. What was missing it learned to replace and what could not be replaced it found substitutes for. Cell by cell, with organs and tissues and nerves, the body had fought its own great battle—and won.

"Spontaneous reconstruction," commented the doctor, touching the forehead of the patient he had not been able to help, merely observe. "It begins where our artificial regenerative processes leave off. I think—oh never mind. There's a lot of development to be done and I don't want to promise anybody something I can't deliver." He eyed Docchi's armless body speculatively.

Webber came in, noisily clanking his mechanical arm and leg. "Heard the good news," he said cheerfully. "Finished my work so I came over." He glanced admiringly at Maureen. "Say, I didn't remember she looked like that."

She was a pleasant sight and not merely because she'd fought off death. Her lips were full and

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)