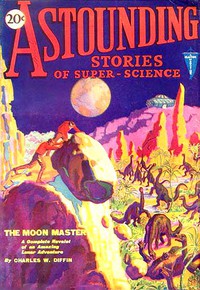

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930 by Various (uplifting novels txt) 📖

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930 by Various (uplifting novels txt) 📖». Author Various

he thin man interrupted with a harsh laugh.

"Come here spying," he said, "and tell me you want to get away from the world." Again he laughed shrilly.

"And I am going to be your little fairy godmother. I wish you were Goodwin himself! I wish I had him here. But you'll get your wish—you'll get your wish. You'll leave the world, you shall, indeed."

He rocked back and forth with appreciation of his humor.

"Didn't know I was all ready to leave, did you? All packed and ready to go. Supplies all stowed away; enough energy stored to carry me millions of miles. Or maybe you did know—may[387]be there are others coming...." He hurried across the room to open a heavy door of split logs in the rock wall.

"I'll fool them all this time," he said; "and you'll never go back to tell them." The door closed behind him.

"Crazy as a bed-bug," Jerry told himself. He strained frantically at the ropes that bound him. "Looks bad for me: the old bird said I'd never go back. Well, what if I die now ... or six months from now? Though I know that doctor was wrong."

He tried to accept his fate philosophically, but the will to live was strong. And one of his wrists felt looser in its bonds.

cross the room his pack lay on the floor, and in it was a heavy forty-five. If he could get the pistol.... A knot pulled loose under his twisting fingers. One hand was free. He worked feverishly at the other wrist.

The ropes were suddenly loose. He pulled himself to his feet, took a moment to regain control of cramped muscles, then flung himself at the pack. When the heavy door opened he was behind it, his pistol in his hand.

There was no struggle: the lanky figure showed no maniacal fury. Instead, the man did a surprising thing. He sank weakly upon the rough bunk where Jerry had lain, his face buried in his thin hands.

"I should have let you die," he said slowly, hopelessly. "I should have let you die. But I couldn't do that.... And now you'll steal my invention for Goodwin."

Jerry was as exasperated as he was amazed.

"I told you," he almost shouted. "I never knew anyone named Goodwin! I don't care a hoot about your invention. And as for letting me die—why didn't you? That's a puzzle: you were about to kill me, anyway."

"No," said the other patiently. "I wasn't going to kill you."

"You said I'd never go back."

"I was going to take you with me."

"Take me where?"

"To the moon," said the drooping figure.

Jerry Foster stared, open-mouthed. The pistol lagged in his limp hand. "To the moon!" he gasped.

Then: "See here," he said firmly. "I've got you where I want you."—he held the pistol steady—"and now I'm going to learn what's back of this. I think you are crazy, absolutely crazy. But, tell me, who are you? What do you think you're doing? What was the meaning of that roaring blast?"

he man looked up. "You don't know?" he asked eagerly. "You really don't?"

"No," said Jerry; "but I'm going to find out."

"Yes," the other agreed. "Yes, you can, now that you've got the upper-hand. I guess I was half crazy when I thought I had been spied out. But I'll tell you."

He sat erect. "I am Thomas J. Winslow," he said, and made the statement as if it were an explanation in itself.

"Well," said Jerry, "that's no burst of illumination to my ignorance. Come again."

The man called Winslow was ready—anxious—to talk.

"I am an inventor. I have made millions of dollars"—Jerry looked at the disheveled apparel of the speaker and smiled—"for other people. The Stillwater syndicate stole my valveless motor. Then I developed my television set. Goodwin beat me out of that: he will have it on the market inside of a year. I swore they should never profit by this, my greatest invention."

Jerry was impressed in spite of himself by the man's earnest simplicity.

"What is it?" he asked.

"I've broken the atom," said Winslow. "First tore the atoms of hydrogen and oxygen apart—dissociated them in the molecule of water—and have resolved them into their energy[388] components. That's what you heard—the reaction. It it self-sustaining, exothermic. That hot blast carried off the heat of my retort."

inslow rose from the bunk. Gone was his listless despondency.

"Put up that gun," he said: "you don't need it now. I think we understand each other better than we did." He crossed with quick strides to the door leading into the cliff.

"Come with me," he told Foster. "I am leaving to-day. You will not stop me. But before I go I will show you something no other man than myself has ever seen."

He led the way through the doorway. There was another room beyond, Jerry saw. It was a cave. Plainly Winslow had taken these caves in the rocks and had made of them a laboratory.

A lantern gave scant illumination: Jerry made out a small electric generator, and that was all. He felt a keen disappointment. Somehow this thin-faced man had communicated to him something of his own belief, his own earnestness.

"What kind of a laboratory do you call this?" he demanded. But the other was busy.

In the wall an opening had been closed with a small iron door, with cement around it. Winslow opened it and reached through. He was evidently adjusting something.

The little dynamo began to hum. There was a crackling hiss from beyond the iron doorway. The opening was flooded with a clear blue light.

Then the roar began. It was tremendous, deafening, in the echoing cave.

"You may look now," said Winslow, and stood aside.

erry peered through. There was another cave beyond. In it was a small metal cylinder, a retort of some kind. The blue light came from a crooked bulb beyond. The retort itself was white-hot, despite a stream of water flowing upon it. A cloud of steam drove continuously out and up through a crevice in the rocks.

The water flowed steadily from some subterranean stream in the limestone formation. It was diverted for its cooling purposes, but a portion also flowed continuously into the retort. Jerry's eyes found this, and he could see nothing else. For, before his eyes, the impossible was occurring.

The retort was small, a couple of feet in diameter. It had no discharge pipes, could hold but a few gallons. Yet into it, in a steady stream, flowed the icy water. Gallons, hundreds of gallons, flowing and flowing, endlessly, into a reservoir which could never hold it.

The inventor watched Foster with complacent satisfaction.

"Where does it go?" Jerry asked incredulously.

"Into nothingness," was the reply. "Or nearly that!"

"See?" He held up a flask of pale green liquid. "And this," he added, exhibiting another that was colorless.

"I have worked here for many months. I have converted thousands of thousands of gallons of water. It has flowed into that retort, never to return. I have gathered this, the product, a few drops at a time.

"The protons and the electrons," he explained, "are re-formed. They are static now, unmoving. Call this what you will—energy or matter—they are one and the same."

"Still," said Jerry, gropingly, "what has all that to do with the moon? You said you were going there."

es," agreed the inventor. I am going, and this is the driving force to carry me there. I pass a certain electric current through these two liquids. I carry the wires to two heavy electrodes. Between them resolution of matter occurs. The current carries these two components to again combine them and form what we call mat[389]ter, the gases hydrogen and oxygen.

"Do I need to tell you of the constant, ceaseless and tremendous explosion that follows?

"But enough of this! You said I was crazy. I gave you a few bad hours. I have shown you this much as a measure of recompense. You have seen what no other man has ever seen. It is enough."

He motioned Foster through the door. The roaring ceased. The inventor returned shortly, the two flasks of liquid in his hands. He transferred both to two metal containers that were ready for the precious load. He carried them with the utmost care as he went out of doors.

Once he returned, and Jerry knew by the crashes from the inner room that the laboratory work was indeed done. There would be nothing left to tell the secret to whomever might come.

He followed Winslow outside, trailing him toward a wooded knoll. There was a clearing among the trees. And in it, hidden from all sides, his eyes found another curious sight.

On the ground rested a dirigible in miniature. Still, it was small, he reasoned, only by comparison with its monster prototype: actually it was a sizable cylinder of aluminum that shone brightly in the sun. It was bluntly rounded at the ends. There were heavy windows, open exhaust ports, a door in the side, pierced through thick walls. Winslow vanished within, while Jerry watched in pitying wonder.

espite its size, it was a toy, an absurd and pitiful toy. Real genius and lunacy had many an over-lapping line, Jerry reflected as he approached to look inside. But he found Winslow in a room surrounded by a network of curving, latticed struts. The machine was no makeshift of a demented builder: it was a beautiful bit of construction that Jerry Foster examined.

"How did you ever get it here?" he marveled. "What you had in the cave you could pack in, but this—all these parts—castings—cases of supplies—"

The inventor did not even turn. He was busy with some final adjustments.

"Flew it in," he said shortly. "Built it in an old shop I owned out near Oakland."

"And it flew?" Jerry was still incredulous.

"Certainly it flew! On a drop or less of the liquids you saw." He pointed to a heavy casting at the center of the machine. There were braces tying it strongly to the entire structure, braces designed to receive and transmit a tremendous thrust.

"This is the generator. Blast expelled through the big exhaust at the stern. These smaller exhausts go above and below—right and left at the bow. Perfect control!"

"And you flew it here!" Jerry was still trying to grasp that incontrovertible fact. "And you were going to take me to the moon, you said."

He looked above him where a pale, silvery segment showed dimly in the sky. "But why the moon?" he questioned. "Even granting that this will fly through space...."

"It will," the other interrupted. "I tried it. Went up to better than fifty miles."

Jerry Foster took a minute to grasp that statement, then continued: "Granting that, why go to the moon? There is nothing there, no air to speak of, no water! It's all known."

he inventor turned to face the younger man in the doorway.

"There is nothing known," he stated. "The modern telescopes reach out a million light years into space. But the one place they have never seen—can never see—is less than two hundred and fifty thousand miles away. The moon, as of course you know, always keeps the same side toward us. The other side of the moon has never been seen.

"Listen," he said, and his deep-set[390] eyes were afire with an intense emotion. "The moon is no tiny satellite; it is a sister planet. It is whirled on the end of a rope (we call it gravitation), swung around and around the earth. How could there be water or anything fluid on this side? It is all thrown to the other side by the centrifugal force. Who knows what life is there? No one—no one! I am going to find out."

Jerry Foster was silent. He was thinking hard. He looked about him at the clean hills, the trees, the world he knew. And he was weighing the secure life he knew against a great adventure.

He took one long breath of the clear air as one who looks his last at a familiar scene. He exhaled slowly. But he stepped firmly into the machine.

"Winslow," he said, "have you any rope handy?"

The inventor was annoyed. "Why, yes, I guess so. Why? What do you want of it?"

"I want you to tie me up again," said Jerry Foster. "I want

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)