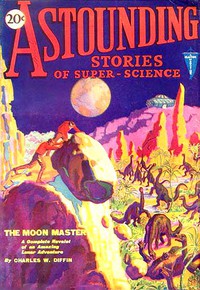

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930 by Various (web based ebook reader TXT) 📖

- Author: Various

Book online «Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930 by Various (web based ebook reader TXT) 📖». Author Various

“Let’s have a rat!”

Hale became so absorbed in the wonders of the laboratory that when lunch time came, Sir Basil had food brought to them. While they were eating a very good vegetable stew, farina, and luscious tropical fruits, a sudden, agonized scream rang out, followed by other screams and wails.

Sir Basil opened the door and looked out. A�a came running forward. Her blue eyes were flooded with tears.

“Oh, Aimu!” she moaned. “A tree fell on Unani Assu.”

She buried her beautiful face in her hands and sobbed aloud.

Sir Basil frowned heavily.

“I can’t lose Unani Assu yet,” he declared. “He is a wonderful help around the laboratory. Is he dead?”

“No. We should rejoice if his time of release had come. But his legs, Aimu! No one wants to suffer and be crippled.”

Even in her distress, the girl’s voice was rich and vibrant, and every tone moved Hale curiously.

“Hurry!” cried the scientist. “Have them bring him here before he dies.”

The girl leaped to her feet and sped away.

“Come, Oakham,” continued Sir Basil. “Here is a rare opportunity for you to see how completely I have mastered the laws that govern organic matter. Help me prepare.”

For several minutes, Hale worked under the scientist’s sharply spoken directions. By the time the injured man was brought to the laboratory, Sir Basil was ready for him.

Unani Assu was still conscious, but his pale face indicated that he had lost much blood. When the improvised stretcher was lowered to the floor, Sir Basil sent all the Indians away.

Unani Assu opened his eyes and called feebly, “A�a!”

303“Be still!” ordered Sir Basil. “A�a is not here.”

“Please!” gasped the dying man. “I want her—my A�a!”

Sir Basil sucked in his breath sharply. “What’s this? Have you been making love to A�a again, after my warning to you?”

The sufferer stirred uneasily. “No!” he panted. “But perhaps my hour of release has come, and I want to look at her—once more.”

The scientist smiled unpleasantly as he eyed the magnificent body which looked like a broken statue in bronze.

“Some human characteristics are strange,” he muttered. “In spite of everything I do, this fellow continues to love A�a: A�a whom I intend for myself.”

He stepped to the apparatus and swiftly changed one of the adjustments.

“Perhaps,” he resumed, with a gleam in his eyes that chilled Hale, “this will forever cure him.”

In another moment, the still, half-dead body was lifted and gently slipped into a compartment.

Before Hale’s horrified gaze fastened on the eye-piece which revealed moving pictures of every process that went on within, Unani Assu’s body was reduced almost instantly to a fine, silvery dust.

“Good God!” he cried. “You have killed him.”

The scientist’s teeth showed in his wide smile. “Think so? Does a woman destroy a dress when she rips it up to make it over?”

“Do you mean me to understand that you can reduce a living body to its basic elements and then rebuild these elements into a remade man?”

“Watch!” warned the scientist.

Hale looked again and saw the silver dust that was once a living body being whirled into a tiny, grublike thing. He saw the grub expand into an embryo, and the embryo develop into a foetus. From now on the development was slower, and he often stopped to talk with Sir Basil.

Once he asked: “If this man had died naturally, could you have brought him back to life?”

Sir Basil shook his head. “No. When once the mind-electron is completely freed from its enslavement by matter, it is forever beyond recall by the body it has just vacated. Like atomic electrons, whose equilibrium disturbed break away from their planetary system and go dashing off into space, only to be drawn into another planetary system, the mind-electron may be enslaved almost immediately by extraneous matter. Had Unani Assu died, his liberated mind-electron might at once have been captured by a jungle flower going to seed. Immediately a new seed would be started. And now the former Unani Assu would be a seed of a jungle flower, later to find new life as a plant.”

Suddenly the scientist threw up his hand and cried: “You see? The Mind will be eternally enslaved as long as there is life! Oh, for the time of deliverance!” He gazed fanatically into space, as though he dreamed magnificently.

Hale observed him thoughtfully. When that great brain weakened, the consequences would be frightful.

Sir Basil, as though he had made a sudden decision, went over to that part of his machine which he called the molecule-disintegrator.

“Oakham!” he called out. “I have taken you partly into my confidence. Now I want to show you something. Come here.”

Hale obeyed with misgivings. The scientist pointed out the window to a group of Indians, anxious relatives of Unani Assu.

“Watch!” he ordered.

Turning one of the projectors on the machine toward the window, he sighted carefully and pressed a button.

Immediately one of the Indians fell to the ground and struggled. His companions 304 began dancing around him in evident joy. Faintly to the laboratory came a familiar chant, which Hale recognized as A�a’s death song.

Dust to dust

Mind to Mind—

He will shed his body

As the green snake sheds his skin.

As Hale watched, the struggling Indian’s body seemed to shrink, and then, instantly, it disappeared.

“Watch them scatter the dust!” said the scientist.

One of the Indians stooped and blew upon the grass.

“What have you done!” Hale gasped. “You’ve killed this one. Oh, I see now! These poor devils are totally ignorant that you are killing them for practice. They worship you while you turn them to—silver dust!” He turned angrily on the scientist as though he longed to strike him.

“Keep cool, young man!” Sir Basil held up his fleshless hand. “There is no death! Change, yes; but no permanent blotting out of consciousness. Can’t you see the horror of it as nature works? When your time for release comes, as it inevitably will, your mind-electron might find new enslavement in a worm!”

Hale’s reply came hotly. “If that is true, why do you murder these poor devils deliberately!”

“My dear Oakham, perhaps you are not so brilliant as I had hoped! All that I have done thus far is only child’s play, in preparation for my real work. Haven’t you guessed by now what I am getting ready to do?”

“No; I’m a poor guesser.”

The scientist made a gesture of mock despair. “Then let me tell you. The molecule-disintegrator is active only on organic structures. When I concentrate it so”—he reached out again, sighted the projector on some point beyond the window and pressed a button—“one single living organism passes out. See that jupati tree by the rock disappear?”

Before Hale’s eyes, the tall, slender tree melted into air.

“But,” continued Sir Basil, “if I should broadcast my molecule-disintegrator on electron magnetic waves, destruction would pass out in all directions, following the curve of the earth’s surface, penetrating earth, air, water.” He wet his lips carefully. “You understand?”

Hale stiffened suddenly. “I understand. No life could survive these vibrations of destruction? Through every corner of the earth where life lurks, they would reach?”

“Yes!” cried Sir Basil. “There would be not a blade of grass, not a living spore, not a hidden egg! Think of it, Oakham! No more would the clean air and the sweet earth reek with life, and at last the ultimate mind-electron would be released forever.”

He was breathing fast, and his emaciated face burned with two red spots.

Hale thought rapidly. He was convinced now that the fate of all life lay within that diabolical network of chemical apparatus.

At last he said: “And what of you and I, Sir Basil? Shall we, too, be caught in this wholesale destruction?”

“Not immediately,” replied the scientist. “Of course, I want to remain in the flesh long enough to be sure that my purpose has been accomplished. I have provided a way for my own safety. If you desire, you may remain with me.” He smiled craftily. “I have planned to keep A�a also, the woman whom I called into life and made as I wished.”

His words pounded against Hale’s tortured ears with almost physical force. With a supreme effort, the young man controlled his rage and despair. A�a needed him too much now for him to risk defeat by showing his emotions.

To Sir Basil he said: “But if all life disappears from the earth, what shall 305 we do for food—you, A�a, and I?”

Sir Basil lifted his brows. “You don’t think I overlooked that, do you? What is food? Various combinations of the basic elements. I who have conquered the atom need never worry about starving to death.”

All this time, the machinery had been humming, and now the humming changed its note to a shrill whistle. Sir Basil went to the eye-piece and looked into it. Opening a door in the machinery, he disappeared inside. He came out soon, flushed and evidently elated.

“Bring the stretcher, Oakham,” he ordered.

Hale brought the stretcher, placing it close to the machine. Then Sir Basil opened a metal door and gently eased out a human body.

It was Unani Assu, unconscious but alive and breathing. Hale, helping the scientist to get the man on the stretcher, noticed that the crushed legs were perfectly healed. Together they bore him to a long seat. The Indian’s eyes were still closed, but his even breathing indicated that he was only sleeping.

Suddenly Hale pointed a finger and cried out. “My God, Sir Basil, look at his hands and feet!”

Unani Assu, still lying like a recumbent bronze statue sculptured by a master, was perfect from shoulder to wrist, from thigh to ankle. But, somewhere in that diabolical machine through which he had passed, his hands and feet had undergone a hideous metamorphism which had transformed them from the well-formed extremities of a splendid young Indian into the hairy paws of a giant rat!

Hale turned away his head, sick with disgust.

Sir Basil cut the silence triumphantly:

“Now he’ll never again face A�a with love in his eyes!”

“What!” broke in Hale. “Did you plan this monstrous thing?”

“Of course! I told you I should forever cure him of his mad infatuation.”

“But why didn’t you kill him, as you killed the others? It would have been the most merciful way.”

Sir Basil showed his teeth in his ugly smile. “A creator is never merciful.”

A quiver passed through the Indian’s body and presently, he sighed deeply and opened his eyes. He seemed dazed, puzzled. He looked from Hale to the scientist, and turned seeking eyes to other parts of the laboratory.

“A�a!” he called weakly. “Where is A�a?”

He pulled himself a little unsteadily to his feet—to the spatulated, hairy rodent feet that had come out of the life-machine. Staggering, he would have fallen, had he not thrown out his arm to steady himself. Instinctively he tried to grasp something for support, and then, for the first time, he discovered his deformity.

Hale was never to forget that expression of horror and disgust that swept over the Indian’s face as he spread open his revolting extremities and stared at them.

A sudden, wild roar of despair rang through the room. “Aimu! My hands!”

The scientist smiled with evident amusement. “You are a grotesque sight, Unani Assu. Do you want to see A�a now?”

The fright and horror faded from the Indian’s face, for now he glared with hate into the mad, mocking eyes.

“You did it!” the Indian ground out. “You’ve made me into a thing from which A�a will run screaming.”

Through the quiet rage of the perfectly spoken English ran a thread of sorrow. “Aimu, whom we considered too holy to name!”

Choking, he hobbled away to the door, which he unbolted. As he passed out into the open, Sir Basil went over to the machine and began sighting the projector which cast forth the ray of destruction.

“No!” cried Hale. “You’ve done enough murder for to-day.”

306The scientist paused. “I was trying to be merciful. And then, I wonder if it is safe to let him go, hating me? Oh, well!” He shrugged his narrow shoulders. “I seldom leave the laboratory, and certainly nothing can harm me here.” He touched the death-projector significantly.

Hale made a mental decision. “I must find out how the damned thing works and put it out of commission.”

With this determination uppermost in his mind, he assumed a more intense interest in the strange laboratory. For the next two days, he assisted Sir Basil so assiduously that he learned much about the operation of the life-machine. And gradually he stopped being horrified as the fascination of producing life in the laboratory grew upon him.

After he had assisted the scientist in building living organisms from basic elements, he ceased to cringe when he remembered that perhaps it was true that A�a was created in the mysterious life-machine.

Once the scientist declared, “She is untainted with inheritance. She is the perfect mate that I called into life so that before I pass from the flesh I may taste that one human emotion I’ve never experienced—love.”

That very night Hale kept a secret tryst with A�a after the village slept. Sweet, virginal A�a, who knew less of the world than a civilized child of twelve—what a sensation she would create in New York with her beauty, her culture, her natural fascination! With her in his arms and an orange tropical moon hanging low in the hot, black sky, he ceased to care that she had no ancestors, for now his one passionate desire was to save her from Sir Basil and to hold her forever for himself.

He might have been content to go on like this for months, tampering with creation in

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)