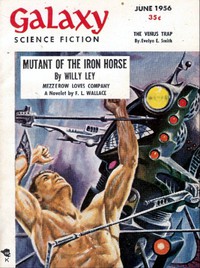

The Venus Trap by Evelyn E. Smith (new reading .TXT) 📖

- Author: Evelyn E. Smith

Book online «The Venus Trap by Evelyn E. Smith (new reading .TXT) 📖». Author Evelyn E. Smith

"And such a charming tune to go with it, too," Magnolia went on. "We have always sung the[Pg 90] music that the wind and the rain have taught us, but, until you came, we never thought of putting words and melody together to form one glorious whole. 'A tree that may in summer wear,'" she caroled in a pleasing contralto, "'a nest of robins in her hair.' By the way, Jim, ever since reading that poem, I've been meaning to ask you precisely what are robins and do you think they'd look well in my hair, by which, I suppose the bard refers, in a somewhat pedestrian flight of fancy, to leaves?"

"They're a kind of bird," he said drearily.

"Birds—nesting in my hair! I wouldn't think of allowing it. But then I suppose Terrestrial birds are quite different from ours? More housebroken, shall we say?"

"Everything's different," James said and, for an irrational moment, he hated everything that was blue that should have been green, everything sweet that should have been vicious, everything intelligent that should have been mindless.

Since matters could not grow much worse, they improved to a degree. After a day or two had passed, Phyllis, being a conscientious girl, came to realize how wrong it had been for her as a Terrestrial immigrant to show overt hostility toward a native of the planet that had welcomed her.

"But how can she be a—a person?" Phyllis wanted to know, when they were inside the cottage, for she had learned to hold her tongue when they were near Magnolia or any of her sisters, who, though they could not speak the language as fluently as she, understood it very well and eavesdropped at every possible opportunity in order, they said, to improve their accents. "She's a tree. A plant. And plants are just vegetables." She stabbed her needle energetically through the tablecloth she was embroidering.

"You mustn't project Terrestrial attitudes upon Elysian ones," James said, patiently looking up from his book. "And don't underestimate Magnolia's capabilities. She has sense organs, and motor organs, too. She can't move from where she is, because she's rooted to the ground, but she's capable of turgor movements, like certain Terrestrial forms of vegetation—for example, the sensitive plant or blue grass."

"Blue grass," Phyllis exclaimed. "I'm sick of blue grass. I want green grass."

"However, these trees have conscious control of their pulvini, whereas the Earth's plants don't, and so they can do a lot of things that Earth plants can't."[Pg 91]

"It sounds like a dirty word to me."

"Pulvini merely means motor organs."

"Oh."

He closed his book, which was a more advanced botany text, covered with the jacket of a French novel in order to spare Phyllis's feelings. "Darling, can't you get it through your pretty head that they're intelligent life-forms? If it'll make it easier for you to think of them as human beings who happen to look like trees, then do that."

"That's exactly what I am doing. And I'm quite sure she thinks of you as a tree who happens to look like a human being."

"Phyllis, sometimes I think you're being deliberately difficult. Do you know one of the reasons why I took such pains to teach Magnolia English? It was that I hoped she would be a companion for you, that you could talk to each other when I had to be away from home."

"Why do you call her Magnolia? She isn't a lot like one."

"Isn't she? I thought she was. You see, I don't know so much botany, after all." Actually, he had picked that name for the tree because it expressed both the arboreal and the feminine at the same time—and also because it was one of the loveliest names he knew. But he couldn't tell Phyllis that; there would be further misunderstanding. "Of course she has a name in her own language, but I can't pronounce it."

"They do have a language of their own then?"

"Naturally, though they don't get much chance to speak it, since they've grown so few and far apart that verbal communication has become difficult. They communicate by a network of roots that they've developed."

"I don't think that's so clever."

"I merely said ... oh, what's the use of trying to explain everything to you? You just don't want to understand."

Phyllis put down her needlework and closed her eyes. "James," she said, opening them again, "it's no use pretending. I've been trying to be sympathetic and understanding, but I can't do it. That tree—I've forced myself to be nice to her, but the more I see of her, the more convinced I am that she's trying to steal you from me."

Phyllis was beginning to poison his mind, he thought, because it had seemed to him also, in his last conversation with Magnolia, that he had discerned more than ordinary warmth in her attitude toward him ... and perhaps a trace of spite toward his wife?

Preposterous! The tree had[Pg 92] only been trying to cheer him up as any friend might reasonably do. After all, a tree and a man.... Nonsense! One had an anabolic metabolism, one a catabolic.

But this was a different kind of tree. She spoke, she read, she was capable of conscious turgor movements. And he, he had often thought secretly, was a different kind of man. Whereas Phyllis....

But that was disloyalty—to the type as well as the individual. The tree could be a companion to him, but she could not give him sons to work his land; she could not give him daughters to populate his planet; moreover, she did not, could not possibly know what human love meant, while Phyllis could at least learn.

"Look, dear," he said, sitting down beside his wife on the couch and taking her hand in his. She didn't draw away this time. "Suppose that what you say is true—not that it is, of course. Just because the tree has a crush on me doesn't mean I necessarily have a crush on her, does it?"

His wife looked up at him, her rose-red lips parted, her moss-gray eyes shining. "Oh, if only I could believe that, James!"

"Anyhow, she doesn't know what the whole thing's about, poor kid!"

"Poor kid!"

"Phyllis, you know you're prettier than any tree." That was not literally true, but reason was useless; he had to make his point in terms she could understand. "And, remember, she's got a lot of rings—she must be centuries old—while you are only nineteen."

"Twenty," Phyllis corrected. "I had a birthday on the ship."

"Well, you certainly must allow me to wish you a happy birthday, darling."

She was in his arms at last; he was about to kiss her, and the tree seemed very remote, when she drew back. "But are you sure she doesn't—she isn't—she can't be watching us?"

"Darling, I swear it!" "Lady, by yonder blessed moon I swear, that tips with silver all these fruit-tree tops".... But he had sense enough not to say it, and Elysium had not one blessed moon, but three, and everything was all right.

For a while anyway.

"I see your wife is developing a corm," the tree remarked, as James paused for a chat. He hadn't much time to be sociable those days, for there was such a lot of work to be done, so many preparations to be made, so many things to be requisitioned from Earth. The supply ships were beginning to come now, bringing necessities and an occasional luxury for those who could afford it.

"She's pregnant," James explained.[Pg 93] "Happened before I left Earth."

"How do you mean?"

"She's about to fruit. Didn't I read that zoology book to you?"

"Yes, but—oh, James, it all seems so vulgar! To fruit without ever having bloomed—how squalid!"

"It all depends on how you look at it," he said. "I—that is, we had hoped that when the baby came, you would be godmother to it. You know what that is, don't you?"

"Of course I do. You read Cinderella to me. I know it's a great honor. But I'm afraid I must decline."

"Why? I thought you were my—our friend."

"Jim, there is something I must confess: my feelings toward you are not merely those of a friend. Although Phyllis doesn't have too many rings of intellect, she is a female, so she knew all along." Magnolia's leaves rustled diffidently. "I feel toward you the way I never felt toward any intelligent life-form, but only toward the sun, the soil, the rain. I sense a tropism that seems to incline me toward you. In fact, I'm afraid, Jim, in your own terms, I love you."

"But you're a tree! You can't love me in my own terms, because trees can't love in the way people can, and, of course, people can't love like trees. We belong to two entirely different species, Maggie. You can't have listened to that zoology book very attentively."

"Our race is a singularly adaptable one or we wouldn't have survived so long, Jim, or gone so far in our particular direction. It's lack of fertility, not lack of enterprise, that's responsible for our decline. And I think your species must be an adaptable one, too; you just haven't really tried. Oh, James, let us reverse the classical roles—let me be the Apollo to your Daphne! Don't let Phyllis stand in our way. The Greek gods never let a little thing like marriage interfere with their plans."

"But I love Phyllis," he said in confusion. "I love you, too," he added, "but in a different way."

"Yes, I know. More like a sister. However, I have plenty of sisters and I don't need a brother."

"We're starting a conservation program," he tried to comfort her. "We have every hope of getting some pollen from the other side of the planet once we have explained to the trees there how far we can make a little go, and you've got to accept it; you mustn't be silly about it."

"It isn't the same thing, Jim, and you know it. One of the penalties of intelligence is a diffusiveness[Pg 94] of the natural instincts. I would rather not fruit at all than—"

"Magnolia, you just don't understand. No matter how much you—well, pursue me, I can never turn into a laurel tree."

"I didn't—"

"Or any kind of tree! Look, some more books were just sent over from Base."

Magnolia gave a rueful rustle. "Just were sent? Didn't they come over a month ago?"

James flushed. "I know I haven't had a chance to do much reading to you in the last few weeks, Maggie—or any at all, in fact—but I've been so busy. After the baby's born, things will be much less hectic and we'll be able to catch up."

"Of course, James. I understand. Naturally your family comes first."

"One of the books that came was an advanced zoology text that might make things a little clearer."

"I should very much like to hear it. When you have the time to spare, that is."

"Tell you what," he said. "I'll get the book and read you the chapter on the reproductive system in mammals. Won't take more than an hour or so."

"If you're in a hurry, it can wait."

"No," he told her. "This will[Pg 95] make me feel a little less guilty about having neglected you."

"Whereupon the umbilical cord is severed," he concluded, "and the human infant is ready to take its place in the world as a separate entity. Now do you understand, Magnolia?"

"No," she said. "Where do the bees come in?"

"I thought you were in such a hurry to get to Base, James," Phyllis remarked sweetly from the doorway, wiping her reddening hands on a dish towel.

"I am, dear." He slipped the book behind his back; it was possible that, in her present state of mind—induced, of course, by her delicate condition—Phyllis might misunderstand his motive in reading that particular chapter of that particular book to that particular tree. "I just stopped for a chat with Magnolia. She's agreed to be godmother to the baby."

"How very nice of her. Earth Government will be so pleased at such a fine example of rapport with the natives. You might even get a medal. Wouldn't that be nice?... James," she hurried on, before he could speak, "you still haven't found any green-leafed plants on the planet, have you? Have you looked everywhere? Have you

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)