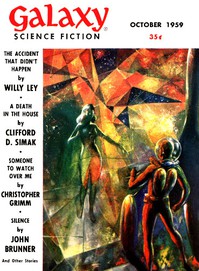

Someone to Watch Over Me by Floyd C. Gale and H. L. Gold (interesting novels in english .txt) 📖

- Author: Floyd C. Gale and H. L. Gold

Book online «Someone to Watch Over Me by Floyd C. Gale and H. L. Gold (interesting novels in english .txt) 📖». Author Floyd C. Gale and H. L. Gold

"Does a ship going through ordinary space see any of us?" the officer returned. "The creatures of hyperspace live on their own planets, and we give those planets a wide berth. Simple as that." He added, "What are you so afraid of, boy? Not a ship's been lost in hyperspace for over two centuries, and there haven't been any blowups for years."

"Blowups?" Len repeated.

"Accidents. A technical term. You've taken worse risks shipping out in those tincan tramps."

Finally, Len gave in—to his own common sense more than to the officer's—and signed up for the voyage. He filled out the necessary forms—hundreds of them, it seemed like. When it came to each line for next of kin, he left a blank on every one.

"Haven't you any relatives at all?" the second officer asked, surprised.

"Not a one." Len didn't bother to mention that half-brother back on Fairhurst; a five-year-old kid isn't much kin to speak of. Besides, the boy probably didn't even know he had a brother—he'd been less than a year old when Len left. One of the barren women must have adopted him and brought him up as her own.

So Len Mattern filled out all the papers and was inscribed on the ship's rolls. And he made the terrible jump through hyperspace for the first time.

People who traveled on spaceships only as passengers never could understand why the Jump was invariably referred to as "terrible." That was because before the ship made the Jump they'd be given drugs, in their cocktails, in their food at dinner, or in their drinking water—and the next day they'd wake up and find they had slept right through the whole thing, so it couldn't be so awful. Of course those who traveled around the universe a lot were bound to catch on. Someday they'd miss a meal or not drink anything and they'd find themselves awake while the ship was Jumping. But the shipping lines didn't take any chances and the aberrant passengers would also find themselves locked in their cabins with smooth metal shutters where the mirrors used to be.

But one thing that couldn't be helped: They couldn't be stopped from looking down at themselves and seeing extra arms and legs; or finding no arms and legs at all, but tentacles instead; or that their skin had turned into shining scales or that there was an extra eye in the back of their head. And when the time came for another Jump, they would ask to be drugged.

However, crewmen couldn't be drugged. They had to be awake to tend the ship. The credo of the Space Service was that you couldn't trust a machine to itself any more than you could trust an extraterrestrial, a non-human. If a man wasn't in charge, ultimately everything would go to pot. That was part of the space tradition, like the primitive axes that hung on the bulkheads, so a man could smash his way to the modern fire-fighting equipment. Except, of course, that if fire really broke out, it would be quicker to press the button that sent the automatic fire-fighting machines into immediate action. But still the axes hung there, because they had always hung there—and, like all the metal on the ship, they had to be kept polished.

Each time a ship made the Jump, the crewmen stayed awake. They saw space and time change before their eyes. They saw their own fellows turn into monsters. It was an awful thing to see, even though they knew it wasn't actually a change, but a shift to another aspect of themselves. Worse than the seeing was the feeling. It was like being turned inside out, organ by organ—your heart and your liver and your guts and all the rest, each carefully turned inside out, the way a woman takes off her gloves, smoothing each one with great precision. The hellish part was that it didn't hurt. A man felt as if he were being twisted and wrenched apart, and it didn't hurt, and it was the wrongness of that more than anything else that—well, that was why the pay was so high on the starships. So many of them went mad.

All this Len Mattern had heard of and had expected—though no amount of expectation could have braced him for that kind of reality. But there was more to it than he had heard, and it was the extra part that the second officer seemed curiously anxious to deny. "You saw nobody—nothing at the portholes," he told Mattern after that first Jump. "You just imagined it."

Mattern had been a spaceman long enough to be able to distinguish imagination from reality. Perhaps the creatures of hyperspace did live on planets, but it seemed they did not breathe the atmosphere of those planets as human beings breathe air, and so they were not confined to them. They could move around freely in the starless dusk of their universe. And, if there was a pact, then they must be intelligent creatures—though he would have known that anyway, for they spoke to him. He could hear them through the tight walls of the ship—less in his ears than his mind—cajoling, entreating, promising. And he shut his ears and his mind, because he was afraid.

At the end of the voyage, he was offered a permanent berth on the Perseus. "We don't usually take crewmen from the Far Planets," the second officer said thoughtfully. "They don't have the training needed. But you're a good deckhand."

Len waited tensely, not knowing whether he did want the job or not.

"The universe is opening up and sooner or later we're going to have to start diversifying our crews, take untrained men, maybe even—" the officer hesitated—"extraterrestrials. Sometimes training can restrict a man to the point where he can't think for himself. Main trouble with untrained men, though, is that often they've got too much imagination. They think things that aren't true, see things that aren't there."

"I understand, sir," Mattern said. "I'll keep my imagination stowed away until it's wanted."

From then on, he had seen no more at the ports than any of his properly conditioned mates.

IV

Len Mattern stayed with the Perseus over three years. Gradually, from things he observed himself, from things his shipmates told him, he learned what little there was to be known about hyperspace. Everything was different there from normspace; even the mechanical properties of things changed. However, Jumping was safe enough, as long as the spaceships didn't stop. As long as they were only passing through that other universe, they were, in a sense, not actually there, so that the elements of which they were composed would not change, although, to the senses, they seemed to.

Unless, of course, the ship collided with something. Then everything became very real. That was what the pact was for—to make sure they didn't collide. Every spaceship had, locked in the captain's cabin, charts of that other universe—charts which gave, in normspace terms, the coordinates of the hyperspace worlds. That way, when a ship made the Jump, there would be no danger of her materializing inside one of the alien planets and destroying both. Even touching one of the hyper-worlds could have a disastrous effect. Only the captains were ever permitted to see these charts; they would be far too dangerous in irresponsible hands.

Len might have grown old in the Perseus' service, if the Hesperia System hadn't been one of her stops, and if he hadn't seen Lyddy there.

Hesperia was a small, rose-pink sun surrounded by four planets and the debris of what once was a fifth. Most solar systems in the Galaxy had asteroid belts like that; some time later, Len found out why. Three of Hesperia's four planets were barren rocks. The fourth, Erytheia, was mostly water, calm water, sometimes blue, sometimes—when the sun was high—violet-tinged. There was land, a small continent in the north, where it was always spring, a slightly larger continent in the south, where it was always summer, and that large island in the west which was said to have a climate better than spring and summer combined.

The atmosphere of Erytheia was what they call Earth type—that is, Man could breathe on it. A very inadequate description, though, because men could breathe the atmosphere of Ziegler's Planet, too, only sometimes it almost seemed worthwhile to stop living in order to stop having to breathe Ziegler's air. Erytheia's atmosphere was gentler and purer than the air of Earth. The native fruits were edible and the local life-forms were small and amiable. But there wasn't enough land for the establishment of a self-supporting colony; it would have bred itself into poverty within a few generations.

What else could be done with a small paradise in a remote sector of space but turn it into a high-class brothel and gambling casino? Only the very rich could afford to travel so far to look at scenery, and by the time they reached their destination, scenery wasn't enough. They wanted some excitement.

Naturally, the Perseus would stop at Hesperia. Naturally, Mattern would see Lyddy, who was one of the seven wonders of that system. She wasn't too many years out from Earth then, and he had never dreamed any woman could be that beautiful.

She was long-necked and slender, unlike the women of the Far Planets, who were mostly squat-built and bred for labor. It seemed to him he had seen her before—in a vision, a dream, who knew where? Certainly never in reality. But he could understand why men would travel light-years for her.

The prices she charged were also astronomical. Still, if he put away his money carefully, in a couple of years he ought to be able to save up enough for a night with her. It was a goal, and he'd never had a goal before, even such a small one; everything had been just aimless drifting. He got a tridi of her and put it up inside the door of his locker and was happy dreaming of her, even if it meant being kidded about her by his shipmates.

When he made the next Jump, he knew for certain that the creatures of hyperspace not only spoke to him through his mind, but could enter it and read it if they chose. He felt very naked and vulnerable. Why couldn't the others on his ship also see the creatures, so that he would not be the sole focus of their attentions?

"Do what we ask," the hyperspacers—the xhindi, they called themselves—said softly, "and you will have enough from just a single voyage to have her for a week, a month, a year. Do what we ask and you can have her for all eternity."

"But all I want is just one night!" he protested.

And they had laughed, and one with a honey-sweet mind had said, "Is that all you want, really all?" Then they began naming the things a man could want—and they certainly seemed to have a full knowledge of humanity and its most secret desires.

Afterward, Len had started to think. It would be nice to have Lyddy all to himself—for a while, anyway. It would be nice to be able to buy her pretty dresses and jewelry. There were other things that would also be nice. Maybe he could have his teeth fixed and his leg straightened. His stepfather had broken it the night his mother died and it had never set properly. With money, he could do a lot of things. He hadn't realized there was so much in the universe to be wanted.

Now his wages began to look as picayune as once they had seemed large. He could make more elsewhere, he told himself; he might not be educated, but he had a good mind, plus rapidly dwindling principles. He didn't need the hyperspacers, though. There were plenty of illegal ways of making money within the framework of normspace activities. So he left the secure monotony of the starship to seek an enterprise which would bring in quick and copious profits.

His first step was to go see a rather disreputable acquaintance of his, Captain Ludolf Schiemann. Schiemann was an ancient spaceman from Earth, who owned and commanded a ramshackle craft of prehistoric design, held together with spit and spells.

Schiemann operated out of Capella IV with cargoes of whatever he could get. He was able to make a living with the Valkyrie only because he would take on jobs that no sane skipper would touch. Some were dangerous; most were illegal into the bargain. The risks were out of all proportion to the profit, which was why the only helper he'd been able to get was Balas—a big, powerful man, not old but mad. He'd been a deckhand on one of the big starships and had broken too early to be entitled to a pension.

Mattern had met old Schiemann at a bar in Burdon, the capital of Capella IV, and had had

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)