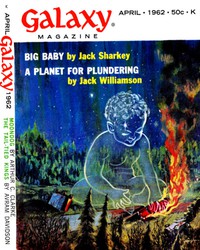

Big Baby by Jack Sharkey (christmas read aloud txt) 📖

- Author: Jack Sharkey

Book online «Big Baby by Jack Sharkey (christmas read aloud txt) 📖». Author Jack Sharkey

Bob shook his head slowly. "You can't? I don't follow."

"You're in the Space Corps," she said. "Maybe you don't know about interstellar colonies. It costs plenty to send people to the stars. The investors want some kind of guarantees for their money. So we're all signed to a ten-year contract. If we fail to fulfill the terms we're sent back to Earth on the next ship going that way."

"Well—I know you're still within the limit," said Bob, "but how does this upset your marriage plans?"

"We go where we're sent," she said simply. "If this colony fails, we'll be sent to a new planet. It may not be the same one. I'll be sent where they need nurses, Jim where they need miners."

Bob felt funny, talking against the colonial program, but the weary despair in the girl's eyes outweighed economic considerations. "You could both renege on your contracts."

"And go back to Earth together?" Jana shook her head. "I couldn't do that, for Jim's sake. He's spent his life at mining, and this is the kind of mining he knows best: Praesodynimium. And there just is no more on Earth."

"He could get something else," said Bob.

"I know. But he might not be happy. After a while, he might blame me for it. Or I'd blame myself. Either way, things just wouldn't be the same. I—I suppose you think I'm foolish, feeling so strongly about him?"

Bob said softly, "Honey, any guy would cut his arm off to get a girl like you. Myself included."

Embarrassed, she looked once more toward the silent figure upon the couch. "You're very kind."

"Not kind," said the tech. "Wistful."

Behind them, a myriad banks of lights and switches flickered, shifted with electric monotony, slowly recording the details, down to the most minute sensory awareness, of the Contact between Jerry Norcriss and the alien....

III

There was at first the feeling of warm sunlight on his flesh, then a pungent scent of crushed foliage, green and heady, very strong and familiar.

As his mind took hold, a whisper of wind hummed into his consciousness and a shimmering golden brightness began to grow upon his closed eyelids. Abruptly, unity of sensation was achieved. Jerry Norcriss "was" in a sunlit part of the woods near the mines, feeling the alien's perceptions as though they were his own.

He crinkled his eyes against the glare, then slowly opened them.

As he blinked his eyes to focus the golden glare, he spotted a strange little cluster of tiny sticks, with miniature leaves sprouting greenly on thread-like branches. Halfway between his face and this fragile copse slithered a brilliant blue line, ribbon-thin, through a serpentine gouge along the earth. On the far side of this trickle lay a rich tumble of soft green velvet, ending at a group of more of those twig-copses. Puzzled, Jerry turned his gaze skyward. Within the warm blue canopy overhead he saw clouds ... but clouds unlike any he'd ever seen for size. None of them could have been more than a foot in diameter. They hung against the sky like cotton-covered basketballs.

He returned his gaze groundward, and for the first time saw the scuffed grayish area of earth between himself and the trickle. A wiry network of metal glittered there, the wires in pairs, and the pairs disappearing into small square punctures against a wall of banked soil.

Then Jerry gasped. His mind had apprehended the implications of his vista so suddenly that he was staggered.

All the facts sprang into proper perspective. The twigs were actually tall trees, the tumble of velvet a wide stretch of grassy sward, the trickle was a rushing blue river, and the tiny wire-network in the grayish area was the tracks for the mine-cars, leading down into the planet through those tiny square adits.

Jerry had unconsciously been receiving sensations in terms of his host's size. A quick calculation showed him that his head must be easily five hundred feet in the air.

Cautiously, he glanced for the first time toward the body of his host, to see what sort of creature he was in Contact with.

There was nothing whatever to be seen.

Yet when he closed his eyelids once again, golden opacity returned. He reopened them thoughtfully. The alien, apparently, could cut off its vision. Yet the eyes of a creature so high must be many feet in diameter. And, at this height, twin opacities would be spotted even from the nearby town.

But no such sight had been reported. Therefore, the lids were opaque only from the inside. Which was ridiculous. Yet it was happening.

Jerry's thoughts were interrupted by a giddy realization. He, in this alien body, was not standing. He was seated cross-legged on the ground. That meant a height of not five hundred feet, but nearer seven hundred.

Cautiously, he extended a hand toward one of the tiny mine-cars. He had a little difficulty directing a hand and arm he could not see; but, by feeling along the earth, he got hold of the dull gray object and tried to lift it. It came up with featherweight ease.

Then, halfway to his eyes, it began to glow, to smoke, to grow terribly hot. And as Jerry released it with a reflex of pain, it burst into white flame and hit the ground as a shapeless gobbet of molten slag. Jerry's hand came to his mouth automatically. He sucked and licked at the sore surfaces of his finger and thumb, trying to drain some of the hurt out of them.

Then he froze.

After a heartbeat, he felt carefully about the interior of his mouth with a forefinger. Gums. Warm, wet, soft-boned toothless gums. Whatever the alien looked like—it was still only a baby.

Which meant—

Quickly Jerry looked at the sky again. Not a cloud had moved. Their rotund fleeciness might have been carven there. He gave himself a mental kick. Hadn't one of his first alien awarenesses been the sound of wind? And yet the grass lay still. The trees stood silent. And the clouds, so nearly over his head that he could have touched one, hung quietly against a perfectly calm sky.

It was not the wind he had heard. It was air. Just molecules of air, as they shifted and flew about at incredible speeds.

The alien-baby's time-sense was occluded, as that of any Earth-baby, by shortness of life. It was the paradox of relative lifetime.

A lifetime, Old Peters had said, training the eager young men who were to become graduate Space Zoologists, is a lifetime. He'd written it on the blackboard so they might understand he was not speaking in circles.

"A lifetime," he'd said, "is the time one spends from birth until any present moment. A lifetime is the actual count of moments of existence from birth. When a baby has been born for an hour, its lifetime is sixty minutes. And to the baby, that sixty minutes is a lifetime."

He'd written the two words on the board, and would point from one to the other as he spoke, so the class could understand the distinction visually, and not have to rely on his inflection to tell which term he'd used.

"A lifetime," he'd continued, "is subjective; a lifetime is objective. The first deals in one's personal sense of time passed. The second is simply readings from a clock. When a man turns ninety, he is usually surprised to find how short a life he's seemed to have had. His ninety years seem hardly longer to him than a single day seemed when he was a baby.

"It is a lucky thing that we cannot penetrate the mind of an intelligent creature. If any of us got into the mind of a baby, we'd soon start going out of our minds with the maddening length of a day's time, seen from a baby's viewpoint. Remember, when you are in Contact with an alien mind, for that immutable forty minutes your sensation of elapsed time will be subject to that of your host. To a baby, forty minutes is forever."

And here Jerry Norcriss was, in a baby's mind.

No wonder no tree had rippled, no cloud had blown. The baby-senses were geared to a near-eternal forty minutes. For all practical purposes, Jerry was stuck in one frame of a movie film, trapped for who-knows-how-long till the next frame came by.

"That's why the car melted!" he realized. "The movement of the car toward me, in my hand, must have been infinitely shorter than the few seconds it seemed to take. I tried to make the mine car move more than five hundred feet, in an actual time less than a thousandth of a second!"

Jerry wasn't overly concerned about the duration itself. He'd been in subjectively-slow creatures before. If things got too boring, he could always doze off; that usually served to pass the time. Even a baby's time-sense jumps long gaps when it sleeps.

The thing that puzzled him was this: If the mine car had burnt up from moving too far too fast, why hadn't the baby's hand and arm been scorched by the motion? The heat of the car had affected it, so that let out inborn heat-resistance....

His hands once again went to his face. He felt not only the features—familiar features, eerily like a human baby's—but the skull-size. When he'd finished, he no longer had reason to doubt that the baby was of an intelligent species. Too much cranial allotment to think any differently.

The whole situation, Jerry mused with grim humor, was screwy. The six-month roborocket could not have missed a creature with such an intense life-pulse, but it had. Contact could not be achieved with an intelligent mind, but it had been. Invisibility—except for certain species of underwater, creatures—was supposed to be impossible for a living organism. Yet here it was.

Three separate impossibles ... all accomplished.

"Still," said Jerry to himself, "that's not the main puzzle. The vanishing of those two shifts of miners is still beyond me. They could, of course, have simply walked head-on into this invisible leviathan. But how fast can a man walk? And would they all have done it? Now, if this kid happened to pick one of them up—" Jerry gave a shudder at the thought of what had happened to that metal mine car. "Still," he sighed, baffled, "a man who bursts into flame is no more fun to hold than a hot mine car. After maybe two or three deaths at the outside, the kid would've learned not to touch them."

Then he had an even eerier thought. If this creature were a baby—where did its mother and father lurk?

The thought of two more invisible giants at large on the planet was unbearable.

Jerry decided to chance losing control over the alien mind, to let its own instincts come to the fore.

There was the possibility that it knew where its folks were, and would try moving in that direction. Or it might cry for its mother, and she'd hurry back. If there were invisible giants, the sooner the colony was informed the better.

As Jerry's control of his host grew tenuous, he could feel the baby's mind taking over once again. Feeble pulsations reached him—nothing like solid thought, but mere urgencies about comfort, food and affection.

Jerry waited, in the background of the unformed mind, for something to happen. Then, suddenly, there was a shifting, something like a metal earthquake. A cold hard light of awareness focused on him, where he'd thought he was safely hidden in the background.

"Who are you?" asked the awareness.

It is not in so many words, of course. A mind speaks to another mind in incredibly swift shorthand. The actual thought-impulse that came to Jerry was a thick wave of curiosity, its stress laid upon identity.

"I am a Learner," Jerry's thought replied. It was a self-sufficient response, since Jerry's concept of all that a Learner was was incorporated in the thought.

"I see," said the alien. "You have memories of antagonism which are now gone from your intent. Explain."

"I came to find a menace. I found a helpless child."

"I see," came the cold, thoughtful reply. "Yes, that is how I sensed it."

"Is your mother around?" asked Jerry. "Or father?"

"Dead," said the awareness. "I am alone."

At the thought, the intense thought of loneliness, a kindred spark flared in Jerry's own mind. The alien caught at the spark, recognized it.

"Strange," it said. "You, too, are alone. But it is a different aloneness."

Jerry's thoughts were whirling in confusion. To be read so easily by a baby was incredible to him. Yet the situation was without precedent. Perhaps a baby's mind was brighter than science gave credit. Since a mind needed no words or manual skills, the mind of a baby might be open to learn the thousand things necessary for adult survival. Maybe as a man learned to

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)