Huckleberry Finn by Dave Mckay, Mark Twain (dark books to read TXT) 📖

- Author: Dave Mckay, Mark Twain

Book online «Huckleberry Finn by Dave Mckay, Mark Twain (dark books to read TXT) 📖». Author Dave Mckay, Mark Twain

Chapter 4

Well, three or four months run along, and it was well into the winter now. I had been to school most all the time and could read and write just a little, and could say the times table up to six times seven is thirty-five, and I don’t think I could ever get any farther than that if I was to live forever. I don’t put no worth in sums, anyway.

At first I hated the school, but by and by I got so I could stand it. Whenever I got too tired I wouldn’t go, and the trouble I got into next day for doing it done me good and made me feel better. So the longer I went to school the easier it got to be. I was getting kind of used to the widow’s ways, too, and they weren’t so rough on me. Living in a house and sleeping in a bed pulled on me pretty tight mostly, but before the cold weather I used to go out secretly and sleep in under the trees sometimes, and so that was a rest to me. I liked the old ways best, but I was getting so I liked the new ones, too, a little. The widow said I was coming along slow but sure, and doing very much okay. She said she wasn’t embarrassed by me at all.

One morning I happened to turn over the salt at breakfast. I reached for some of it as quickly as I could to throw over my left shoulder and keep off the bad luck, but Miss Watson was in ahead of me, and cut me off. She says, “Take your hands away, Huckleberry; you’re always so messy!” The widow put in a good word for me, but that weren’t going to keep off the bad luck, I knowed that well enough.

I started out, after breakfast, feeling worried and weak, and thinking about where it was going to fall on me, and what it was going to be. There's ways to keep off some kinds of bad luck, but this weren’t one of them kind; so I never tried to do anything, but just went along slowly and low-spirited and on the watch for it.

I went down to the front garden and climbed over the gate where you go through the high board fence. There was an inch of new snow on the ground, and I seen someone’s footprints.

They had come up from the rock yard and stood around the gate a while, and then went on around the garden fence. It was funny they hadn’t come in, after standing around so. I couldn’t make it out. It was very strange. I was going to follow around, but I bent down to look at the footprints first. I didn’t see anything special at first, but then I did. There was a cross in the left heel made with big nails, to keep off the devil.

I was up in a second and running down the hill. I looked over my shoulder every now and then, but I didn’t see nobody. I was at Judge Thatcher’s as fast as I could get there. He said: “Why, my boy, you are breathing so heavily. Did you come for your interest?”

“No, sir,” I says; “Is there some for me?”

“Oh, yes, come in last night for half a year -- over a hundred and fifty dollars. A lot of wealth for you. You had better let me put it back with your six thousand, because if you take it you’ll spend it.”

“No, sir,” I says, “I don’t want to spend it. I don’t want it at all -- or the six thousand either. I want you to take it; I want to give it to you -- the six thousand and all.”

He looked surprised. He couldn’t seem to make it out. He says: “Why, what can you mean, my boy?”

I says, “Don’t you ask me no questions about it, please. You’ll take it -- won’t you?”

He says: “Well, I’m confused. Is something wrong?”

“Please take it,” says I, “and don’t ask me nothing -- then I won’t have to tell no lies.”

He studied a while, and then he says: “Oh! I think I see what you’re saying. But you need to sell your wealth to me -- not give it. That’s the right way.”

Then he wrote something on a paper and read it over, and says: “There; you see it says ‘for a sum.’ That means you have sold it to me. Here’s a dollar for you. Now you sign it.”

So I signed it, and left.

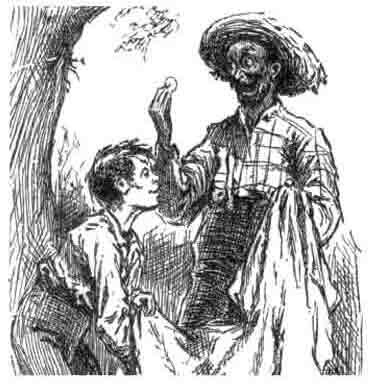

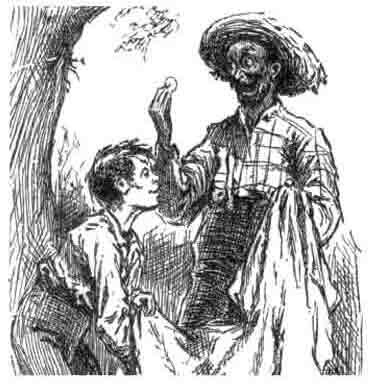

Miss Watson’s slave, Jim, had a hair-ball as big as your fist, which had been took out of the fourth stomach of a cow, and he used it to do magic. He said there was a spirit in it, and it knowed everything. So I went to him that night and told him pap was here again, for I found his footprints in the snow. What I wanted to know was, what he was going to do, and was he going to stay? Jim got out his hair-ball and said something over it, and then he held it up and dropped it on the floor. It fell pretty solid, and only moved about an inch. Jim tried it again, and then another time, and it acted just the same. Jim got down on his knees, and put his ear against it and listened. But it weren’t no use; he said it wouldn’t talk. He said sometimes it wouldn’t talk without money. I told him I had an old counterfeit coin that weren’t no good because the yellow metal showed through the silver a little, and it wouldn’t pass anyway, even if the yellow didn’t show, because it was so smooth it felt like it had oil on it, and that would tell on it every time. (I wasn’t going to say nothing about the dollar I got from the judge.) I said it was pretty bad money, but maybe the hair-ball would take it, because maybe it wouldn’t know the difference. Jim smelled it and squeezed it with his teeth and rubbed it, and said he could do something so the hair-ball would think it was good. He said he would cut open a potato and put the coin in between and keep it there all night, and next morning you couldn’t see no yellow, and it wouldn’t feel like oil no more, and so anyone in town would take it in a minute, let alone a hair-ball. Well, I knowed a potato would do that before, but I didn’t think of it at the time.

Jim put the coin under the hair-ball, and got down and listened again. This time he said the hair-ball was all right. He said it would tell my whole future if I wanted it to. I says, go on. So the hair-ball talked to Jim, and Jim told it to me.

He says: “Your old father don’t know yet what he’s a-gwyne to do. Sometimes he thinks he’ll go away, den again he thinks he’ll stay. De best way is to rest easy and let de old man take his own way. Dey’s two angels hanging round about him. One of ‘em is white and full of light, and t’other is black. De white one gets him to go right a little, den de black one sails in and breaks it all up. A body can’t tell yet which one gwyne to lead him at de last. But you is all right. You gwyne to have a lot of trouble in your life, and a lot of happiness. Sometimes you gwyne to get hurt, and sometimes you gwyne to get sick; but every time you’s gwyne to get well again. Dey’s two girls flying about you in your life. One of ‘em’s light and t’other is dark. One is rich and t’other is poor. You’s gwyne to marry de poor one first and de rich one by and by. You wants to keep away from de water as much as you can, and don’t do anything dangerous, because it’s down in de ball dat you’s gwyne to be hanged.”

Chapter 5

When I took a candle and went up to my room that night there sat pap himself!

I had shut the door to. Then I turned around. and there he was. I used to be scared of him all the time, he hit me so much. I thought I was scared now, too; but in a minute I seen I was wrong -- that is, after the first surprise, as you may say, when my breathing kind of stopped, he being so not what I was thinking would be there; then right away after, I seen I wasn’t scared of him worth worrying about.

He was most fifty, and he looked it. His hair was long and messy and dirty, and was hanging down so you could see his eyes looking through like he was behind vines. It was all black, no grey; so was his long, confused beard. There weren’t no colour in his face, where his face showed; it was white; not like another man’s white, but a white to make a body sick, a white to make a body’s skin turn cold -- a tree-frog white, a fish-stomach white. As for his clothes -- just pieces of broken cloth, that was all. He had one ankle resting on the other knee; the shoe on that foot was broken open, and two of his toes were sticking through, and he worked them now and then. His hat was lying on the floor -- an old black hat with a concave top.

I stood a-looking at him; he sat there a-looking at me, with his chair leaning back a little. I put the candle down. I could see the window was up; so he had climbed in by the tool room. He kept a-looking me all over. By and by he says: “Straight clothes -- very. You think you’re the best part of a big head now, don’t you?”

“Maybe I am, maybe I ain’t,” I says.

“Don’t you give me none of your lip,” says he. “You’ve put on way too many airs since I been away. I’ll take you down a step or two before I get done with you. You’re educated, too, they say -- can read and write. You think you’re better than your father, now, don’t you, because he can’t? I’ll take it out of you. Who told you you might be part of such high minded foolishness, hey? -- who told you you could?”

“The widow. She told me.”

“The widow, hey? -- and who told the widow she could put in her shovel about a thing that ain’t none of her business?”

“Nobody never told her.”

“Well, I’ll learn her to mix things up. And you drop that school, you hear? I’ll learn people to bring up a boy to put on airs over his own father and let on to be better than what he is. Don't let me catch you going to that school again, you hear? Your mother couldn’t read, and she couldn’t write either, before she died. None of the family couldn’t before they died. I can’t; and here you’re a-lifting yourself up like this. I ain’t the man to stand it --

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)