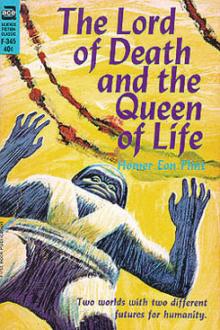

The Lord of Death and the Queen of Life by Homer Eon Flint (novels in english .TXT) 📖

- Author: Homer Eon Flint

Book online «The Lord of Death and the Queen of Life by Homer Eon Flint (novels in english .TXT) 📖». Author Homer Eon Flint

Without exception, it resembled the central group; all the figures were neckless, and all much more heavily built than any people on earth. There were several female figures; they had the same general build, and in every case were so placed as to enhance the glory of the males. In one group the woman was offering up food and drink to a resting worker; in another she was being carried off, struggling, in the arms of a fairly good-looking warrior.

Dr. Kinney led the way into the building. As in the other structure, there was no door. The space seemed to be but one story in height, although that had the effect of a cathedral. The whole of the ceiling, irregularly arched in a curious, pointed manner, was ornamented with grotesque figures; while the walls were also partially formed of squat, semi-human statues, set upon huge, triangular shafts. In the spaces between these outlandish pilasters there had once been some sort of decorations, A great many photos were taken here.

As for the floor, it was divided in all directions by low walls. About five and a half feet in height, these walls separated the great room into perhaps a hundred triangular compartments, each about the size of an ordinary living room. Broad openings, about five feet square, provided free access from one compartment to any other. The men from the earth, by standing on tiptoes, could see over and beyond this system.

"Wonder if these walls were supposed to cut off the view?" speculated the doctor. "I mean, do you suppose that the Mercurians were such short people as that?" His question had to go unanswered.

They stepped into the nearest compartment, and were on the point of pronouncing it bare, when Jackson, with an exclamation, excitedly brushed away some of the dust and showed that the presumably solid walls were really chests of drawers. Shallow things of that peculiar metal, these drawers numbered several hundred to the compartment. In the whole building there must have been millions.

Once more the dust was carefully removed, revealing a layer of those curious rolls or reels, exactly similar to what had been found in the tool chest in the shell works. A careful examination of the metallic tape showed nothing whatever to the naked eye, although the doctor fancied that he made out some strange characters on the little boxes themselves.

His view was shortly proved. Finding drawer after drawer to contain a similar display, varying from one to a dozen of the diminutive ribbons, Van Emmon adopted the plan of gently blowing away the dust from the faces of the drawers before opening them. This revealed the fact that each of the shallow things was neatly labeled!

Instantly the three were intent upon this fresh clue. The markings were very faint and delicate, the slightest touch being enough to destroy them. To the untrained eye, they resembled ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics; to the archeologist, they meant that a brand-new system of ideographs had been found.

Suddenly Jackson straightened up and looked about with a new interest. He went to one of the square doorways and very carefully removed the dust from a small plate on the lintel. He need not have been so careful; engraved in the solid metal was a single character, plainly in the same language as the other ideographs.

The architect smiled triumphantly into the inquiring eyes of his friends. "I won't have to eat my hat," said he. "This is a sure-enough city, all right, and this is its library!"

Smith was still busy on the little machine when they returned to the cube. He said that one part of it had disappeared, and was busily engaged in filing a bit of steel to take its place. As soon as it was ready, he thought, they could see what the apparatus meant.

The three had brought a large number of the reels. They were confident that a microscopic search of the ribbons would disclose something to bear out Jackson's theory that the great structure was really a repository for books, or whatever corresponded with books on Mercury.

"But the main thing," said the doctor, enthusiastically, "is to get over to the 'twilight band.' I'm beginning to have all sorts of wild hopes."

Jackson urged that they first visit the big "mansion" on the outskirts of this place; he said he felt sure, somehow, that it would be worth while. But Van Emmon backed up the doctor, and the architect had to be content with an agreement to return in case their trip was futile.

Inside of a few minutes the cube was being drawn steadily over toward the left or western edge of the planet's sunlit face. As it moved, all except Smith kept close watch on the ground below. They made out town after town, as well as separate buildings; and on the roads were to be seen a great many of those octagonal structures, all motionless.

After several hundred miles of this, the surface abruptly sloped toward what had clearly been the bed of an ocean. No sign of habitations here, however; so apparently the water had disappeared after the humans had gone.

This ancient sea ended a short distance from the district they were seeking. A little more travel brought them to a point where the sun cast as much shadow as light on the surface. It was here they descended, coming to rest on a sunlit knoll which overlooked a small, building-filled valley.

According to Kinney's apparatus, there was about one-fortieth the amount of air that exists on the earth. Of water vapor there was a trace; but all their search revealed no human life. Not only that, but there was no trace of lower animals; there was not even a lizard, much less a bird. And even the most ancient-looking of the sculptures showed no creatures of the air; only huge, antediluvian monsters were ever depicted.

They took a great many photos as a matter of course. Also, they investigated some of the big, octagonal machines in the streets, finding them to be similar to the great "tanks" that were used in the war, except that they did not have the characteristic caterpillar tread; their eight faces were so linked together that the entire affair could roll, after a jolting, slab-sided, flopping fashion. Inside were curious engines, and sturdy machines designed to throw the cannon-shells they had seen; no explosive was employed, apparently, but centrifugal force generated in whirling wheels. Apparently these cars, or chariots, were universally used.

The explorers returned to the cube, where they found that Smith, happening to look out a window, had spied a pond not far off. The three visited it and found, on its banks, the first green stuff they had seen; a tiny, flowerless salt grass, very scarce. It bordered a slimy, bluish pool of absolutely still fluid. Nobody would call it water. They took a few samples of it and went back.

And within a few minutes the doctor slid a small glass slide into his microscope, and examined the object with much satisfaction. What he saw was a tiny, gelatinlike globule; among scientists it is known as the amoeba. It is the simplest known form of life—the so-called "single cell." It had been the first thing to live on that planet, and apparently it was also the last.

V THE CLOSED DOORAs they neared Jackson's pet "mansion" each man paid close attention to the intervening blocks. For the most part these were simply shapeless ruins; heaps of what had once been, perhaps, brick or stone. Once they allowed the cube to rest on the top of one of these mounds; but the sky-car's great weight merely sank it into the mass. There was nothing under it save that same sandy dust.

Apparently the locality they were approaching had been set aside as a very exclusive residence district for the elite of the country. Possibly it contained the homes of the royalty, assuming that there had been a royalty. At any rate the conspicuous structure Jackson had selected was certainly the home of the most important member of that colony.

When the three, once more in their helmets and suits, stood before the low, broad portico which protected the entrance to that edifice, the first thing they made out was an ornamental frieze running across the face. In the same bold, realistic style as the other sculpture, there was depicted a hand-to-hand battle between two groups of those half savage, half cultured monstrosities. And in the background was shown a glowing orb, obviously the sun.

"See that?" exclaimed the doctor. "The size of that sun, I mean! Compare it with the way old Sol looks now!"

They took a single glance at the great ball of fire over their heads; nine times the size it always seemed at home, it contrasted sharply with the rather small ball shown in the carvings.

"Understand?" the doctor went on. "When that sculpture was made, Mercury was little nearer the sun than the earth is now!"

The builder was hugely impressed. He asked, eagerly: "Then probably the people became as highly developed as we?"

Van Emmon nodded approvingly, but the doctor opposed. "No; I think not, Jackson. Mercury never did have as much air as the earth, and consequently had much less oxygen. And the struggle for existence," he went on, watching to see if the geologist approved each point as he made it, "the struggle for life is, in the last analysis, a struggle for oxygen.

"So I would say that life was a pretty strenuous proposition here, while it lasted. Perhaps they were—" He stopped, then added: "What I can't understand is, how did it happen that their affairs came to such an abrupt end? And why don't we see any—er—indications?"

"Skeletons?" The architect shuddered. Next second, though, his face lit up with a thought. "I remember reading that electricity will decompose bone, in time." And then he shuddered again as his foot stirred that lifeless, impalpable dust. Was it possible?

As they passed into the great house the first thing they noted was the floor, undivided, dust-covered, and bare, except for what had perhaps been rugs. The shape was the inevitable equilateral triangle; and here, with a certain magnificent disregard for precedent, the builders had done away with a ceiling entirely, and instead had sloped the three walls up till they met in a single point, a hundred feet overhead. The effect was massively simple.

In one corner a section of the floor was elevated perhaps three feet above the rest, and directly back of this was a broad doorway, set in a short wall. The three advanced at once toward it.

Here the electric torch came in very handy. It disclosed a poorly lighted stairway, very broad, unrailed, and preposterously steep. The steps were each over three feet high.

"Difference in gravitation," said the doctor, in response to Jackson's questioning look. "Easy enough for the old-timers, perhaps." They struggled up the flight as best they could, reaching the top after over five minutes of climbing.

Perhaps it was the reaction from this exertion; at all events each felt a distinct loss of confidence as, after regaining their wind, they again began to explore. Neither said anything about it to the others; but each noted a queer sense of foreboding, far more disquieting than either of them had felt when investigating anything else. It may have been due to the fact that, in their hurry, they had not stopped to eat.

The floor they were on was fairly well lighted with the usual oval windows. The space was open, except that it contained the same kind of dividing walls they had found in the library. Here, however, each compartment contained but one opening, and that not uniformly placed. In fact, as the three noted with a growing uneasiness, it was necessary to pass through every one of them in order to reach the corner farthest, from the ladderlike stairs. Why it should make them uneasy, neither could have said.

When they were almost through the labyrinth, Van Emmon, after standing on tiptoes for the tenth time, in order to locate himself, noted something that had escaped their attention before. "These compartments used to be covered over," he said, for some reason lowering his voice. He pointed out niches in the walls, such as undoubtedly once held the ends of heavy timbers. "What was this place, anyhow? A trap?"

Unconsciously they lightened their steps as they neared the last compartment. They found, as expected, that it was another stairwell. Van Emmon turned the light upon every corner of the place before going any further; but except for a formless heap of rubbish in one corner, which they did not investigate, the place was as bare as the rest of the floor.

Again they climbed, this time for a much shorter distance; but Jackson, slightly built chap that he was, needed a little help on the steep stairs. They were not

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)