Huckleberry Finn by Dave Mckay, Mark Twain (dark books to read TXT) 📖

- Author: Dave Mckay, Mark Twain

Book online «Huckleberry Finn by Dave Mckay, Mark Twain (dark books to read TXT) 📖». Author Dave Mckay, Mark Twain

“Blamed if I know -- that is, what’s become of the raft. That stupid old man had done some business and got forty dollars, and when we found him in the pub some of the local boys had tricked him out of every cent but what he’d spent for whiskey; and when I got him home late last night and found the raft gone, we said, ‘That little devil has robbed our raft and shook us, and run off down the river.’”

“I wouldn’t shake my black man, would I? -- the only black man I had in the world, and the only wealth.”

“We never thought of that. Truth is, I think we’d come to think of him as our black man; yes, we did think that -- God knows we had trouble enough for him. So when we seen the raft was gone and we had nothing, there weren’t anything for it but to give The King’s Foolishness another shake. And I’ve been two days now without a drink. Where’s that ten cents? Give it here.”

I had enough other money, so I give him ten cents, but begged him to spend it for something to eat, and give me some, because it was all the money I had, and I hadn’t had nothing to eat since yesterday. He never said nothing. The next minute he turns on me and says:

“Do you think that black man would blow on us? We’d skin him if he done that!”

“How can he blow? Ain’t he run off?”

“No! The old man sold him, and never give any to me, and the money’s gone.”

“Sold him?” I says, and started to cry. “He's my black man, and that was my money. Where is he? -- I want my black man.”

“Well, you can’t get your black man, that’s all -- so dry up your crying. Look here -- do you think you’d try to blow on us? I don’t think I trust you. Why, if you was to blow on us -- “

He stopped, but I never seen the duke look so ugly out of his eyes before. I went on a-crying, and says: “I don’t want to blow on nobody; and I ain’t got no time to blow, anyway. I got to turn out and find my black man.”

He looked kind of worried, and stood there with his papers in his hands, thinking, and squeezing up the front of his head. At last he says: “I’ll tell you something. We got to be here three days. If you’ll promise you won’t blow, and won’t let the black man blow, I’ll tell you where to find him.”

So I promised, and he says: “A farmer by the name of Silas Ph -- -- “ and then he stopped. You see, he started to tell me the truth; but when he stopped that way, and started to study and think again, I believed he was changing his plan. And so he was. He wouldn’t trust me; he wanted to make sure of having me out of the way the whole three days. So pretty soon he says: “The man that has him is named Abram Foster -- Abram G. Foster -- and he lives forty miles back here in the country, on the road to Lafayette.”

“All right,” I says, “I can walk it in three days. And I’ll start this very afternoon.”

“No you won't, you’ll start now; and don’t you lose any time about it, either, or do any talking by the way. Just keep a tight tongue in your head and move right along, and then you won’t get into trouble with us, do you hear?”

That was the rule I wanted, and that was the one I had been playing for. I wanted to be left free to work my plans.

“So move out,” he says; “and you can tell Mr. Foster what- ever you want to. Maybe you can get him to believe that Jim is your black man -- some stupid people don’t ask for papers -- at least I’ve heard there’s such down South here. And when you tell him the advertisement and the reward’s false, maybe he’ll believe you when you tell him why we printed them in the first place. Go along now, and tell him anything you want to; but just don’t work your mouth any between here and there.”

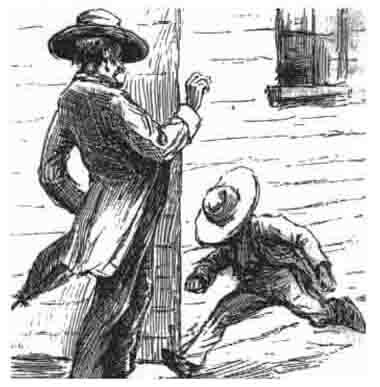

So I left, and headed for the back country. I didn’t look around, but I kind of felt like he was watching me. But I knowed I could tire him out at that. I went straight out in the country as much as a mile before I stopped; then I came back through the trees toward Phelps’s. I knew I needed to start in on my plan straight off without wasting time, because I wanted to stop Jim’s mouth until these two could get away. I didn’t want no trouble with their kind. I’d seen all I wanted to of them, and wanted to get perfectly free of them.

Chapter 32

When I got there it was all quiet and Sunday-like, and hot and sunny; the workers was gone to the fields; and there was them kind of soft sounds of flies in the air that makes it seem so empty and like everybody’s dead and gone; and if a little wind shakes the leaves it makes you feel sad, because you feel like it’s spirits whispering -- spirits that’s been dead ever so many years -- and you always think they’re talking about you. As a general thing it makes a body wish he was dead, too, and done with it all.

Phelps’s was one of those little one-horse cotton farms, and they all look the same. A timber fence around a yard; steps over the fence made out of vertical logs in the ground, like barrels of different lengths, to climb over the fence with; some places in the big yard with a little sick grass growing in it, but mostly just smooth dirt, like an old hat with the soft part rubbed off; big log house for the white people -- with the holes stopped up with mud that had been white-washed some time or another; log kitchen, with a big wide, roofed footpath joining it to the house; log smoke-house back of the kitchen; three little log servant cabins in a line t’other side of the smoke-house; one little room all by itself away down against the back fence, and some other buildings down a piece the other side; box for ashes and a big kettle to make soap by the little room; bench by the kitchen door, with a bucket of water; dog asleep there in the sun; more dogs asleep around about; about three trees away off in a corner; some berry bushes in one place by the fence; outside of the fence a garden and a field of watermelons; then the cotton fields starts, and after the fields the trees.

I went around and climbed over the steps by the box of ashes, and started for the kitchen. When I got a little ways I heard the quiet sound of a spinning-wheel going up and then coming down again; and then I knowed for sure I wished I was dead -- for that IS the saddest sound in the whole world.

I went right along, not fixing up any special plan, but just trusting to God to put the right words in my mouth when the time come; for I’d learned that He always did put the right words in my mouth if I left it alone.

When I got half-way, first one dog and then another got up and went for me, and so I stopped and faced them, and didn’t move. And such a lot of noise they made! In a few seconds I was kind of the middle of a wheel, as you may say, with a circle of fifteen dogs pointing at me in the centre, with their necks and noses reaching up toward me, making all kinds of noise; and more a-coming; you could see them sailing over fences and around corners from everywhere.

A black woman come running out of the kitchen with a stick in her hand, singing out, “Stop that you Tiger! you Spot! get out of here!” and she hit first one and then another of them with the stick and sent them running off crying, and then the others followed; and the next second half of them come back, shaking their tails around me, and making friends with me. There ain’t no bad in a dog, no way.

And behind the woman comes a little black girl and two little black boys without anything on but shirts, and they was hanging onto their mother’s dress, and looked out from behind her at me, shy, the way they always do. And here comes the white woman running from the house, about forty-five or fifty years old, with a stick in her hand too; and behind her comes her little white children, acting the same way the little black ones did. She was smiling all over so she could hardly stand -- and says: “It’s you, at last! -- ain’t it?”

I out with a “Yes ma'am” before I thought.

She took me and hugged me tight; and then held me by both hands and shook and shook; and the tears come in her eyes, and run down over; and she couldn’t seem to hug and shake enough, and kept saying, “You don’t look as much like your mother as I thought you would; but I’m not worried about that, I’m so glad to see you! My, my, it does seem like I could eat you up! Children, it’s your cousin Tom! -- tell him hello.”

But they dropped their heads, and put their fingers in their mouths, and went behind her. So she run on: “Lize, hurry up and get him a hot breakfast right away -- or did you get your breakfast on the boat?”

I said I had got it on the boat. So then she started for the house,leading me by the hand, and the children coming after. When we got there she sat me down in a chair, and sat herself down on a little box in front of me, holding both of my hands, and says:

“Now I can have a good look at you; and, my, my, I’ve been hungry for it many a time, all these long years, and it’s come at last! We been thinking you would be here for two days and more. What kept you? -- boat go to ground?”

“Yes ma'am -- she -- “

“Don’t say ma'am; say Aunt Sally. Where’d she go to ground?”

I didn’t really know what to say, because I didn’t know if the boat would be coming up the river or down. But I go a good lot on feelings; and my feeling said she would be coming

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)