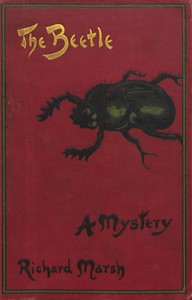

The Beetle: A Mystery by Richard Marsh (romantic love story reading .txt) 📖

- Author: Richard Marsh

Book online «The Beetle: A Mystery by Richard Marsh (romantic love story reading .txt) 📖». Author Richard Marsh

‘Why do you ask?’

‘I beg your pardon, sir, but I saw a Harab myself about a hour ago,—leastways he looked like as if he was a Harab.’

‘What sort of a looking person was he?’

‘I can’t ’ardly tell you that, sir, because I didn’t never have a proper look at him,—but I know he had a bloomin’ great bundle on ’is ’ead.… It was like this, ’ere. I was comin’ round the corner, as he was passin’, I never see ’im till I was right atop of ’im, so that I haccidentally run agin ’im,—my heye! didn’t ’e give me a downer! I was down on the back of my ’ead in the middle of the road before I knew where I was and ’e was at the other end of the street. If ’e ’adn’t knocked me more’n ’arf silly I’d been after ’im, sharp,—I tell you! and hasked ’im what ’e thought ’e was a-doin’ of, but afore my senses was back agin ’e was out o’ sight,—clean!’

‘You are sure he had a bundle on his head?’

‘I noticed it most particular.’

‘How long ago do you say this was? and where?’

‘About a hour ago,—perhaps more, perhaps less.’

‘Was he alone?’

‘It seemed to me as if a cove was a follerin’ ’im, leastways there was a bloke as was a-keepin’ close at ’is ’eels,—though I don’t know what ’is little game was, I’m sure. Ask the pleesman—he knows, he knows everythink, the pleesman do.’

I turned to the ‘pleesman.’

‘Who is this man?’

The ‘pleesman’ put his hands behind his back, and threw out his chest. His manner was distinctly affable.

‘Well,—he’s being detained upon suspicion. He’s given us an address at which to make inquiries, and inquiries are being made. I shouldn’t pay too much attention to what he says if I were you. I don’t suppose he’d be particular about a lie or two.’

This frank expression of opinion re-aroused the indignation of the gentleman on the form.

‘There you hare! at it again! That’s just like you peelers,—you’re all the same! What do you know about me?—Nuffink! This gen’leman ain’t got no call to believe me, not as I knows on,—it’s all the same to me if ’e do or don’t, but it’s trewth what I’m sayin’, all the same.’

At this point the Inspector re-appeared at the pigeon-hole. He cut short the flow of eloquence.

‘Now then, not so much noise outside there!’ He addressed me. ‘None of our men have seen anything of the person you’re inquiring for, so far as we’re aware. But, if you like, I will place a man at your disposal, and he will go round with you, and you will be able to make your own inquiries.’

A capless, wildly excited young ragamuffin came dashing in at the street door. He gasped out, as clearly as he could for the speed which he had made:

‘There’s been murder done, Mr Pleesman,—a Harab’s killed a bloke.’

‘Mr Pleesman’ gripped him by the shoulder.

‘What’s that?’

The youngster put up his arm, and ducked his head, instinctively, as if to ward off a blow.

‘Leave me alone! I don’t want none of your ’andling!—I ain’t done nuffink to you! I tell you ’e ’as!’

The Inspector spoke through the pigeon-hole.

‘He has what, my lad? What do you say has happened?’

‘There’s been murder done—it’s right enough!—there ’as!—up at Mrs ’Enderson’s, in Paradise Place,—a Harab’s been and killed a bloke!’

CHAPTER XLIV.THE MAN WHO WAS MURDERED

The Inspector spoke to me.

‘If what the boy says is correct it sounds as if the person whom you are seeking may have had a finger in the pie.’

I was of the same opinion, as, apparently, were Lessingham and Sydney. Atherton collared the youth by the shoulder which Mr Pleesman had left disengaged.

‘What sort of looking bloke is it who’s been murdered?’

‘I dunno! I ’aven’t seen ’im! Mrs ’Enderson, she says to me! “’Gustus Barley,” she says, “a bloke’s been murdered. That there Harab what I chucked out ’alf a hour ago been and murdered ’im, and left ’im behind up in my back room. You run as ’ard as you can tear and tell them there dratted pleese what’s so fond of shovin’ their dirty noses into respectable people’s ’ouses.” So I comes and tells yer. That’s all I knows about it.’

We went four in the hansom which had been waiting in the street to Mrs Henderson’s in Paradise Place,—the Inspector and we three. ‘Mr Pleesman’ and ‘’Gustus Barley’ followed on foot. The Inspector was explanatory.

‘Mrs Henderson keeps a sort of lodging-house,—a “Sailors’ Home” she calls it, but no one could call it sweet. It doesn’t bear the best of characters, and if you asked me what I thought of it, I should say in plain English that it was a disorderly house.’

Paradise Place proved to be within three or four hundred yards of the Station House. So far as could be seen in the dark it consisted of a row of houses of considerable dimensions,—and also of considerable antiquity. They opened on to two or three stone steps which led directly into the street. At one of the doors stood an old lady with a shawl drawn over her head. This was Mrs Henderson. She greeted us with garrulous volubility.

‘So you ’ave come, ’ave you? I thought you never was a-comin’ that I did.’ She recognised the Inspector. ‘It’s you, Mr Phillips, is it?’ Perceiving us, she drew a little back. ‘Who’s them ’ere parties? They ain’t coppers?’

Mr Phillips dismissed her inquiry, curtly.

‘Never you mind who they are. What’s this about someone being murdered.’

‘Ssh!’ The old lady glanced round. ‘Don’t you speak so loud, Mr Phillips. No one don’t know nothing about it as yet. The parties what’s in my ’ouse is most respectable,—most! and they couldn’t abide the notion of there being police about the place.’

‘We quite believe that, Mrs Henderson.’

The Inspector’s tone was grim.

Mrs Henderson led the way up a staircase which would have been distinctly the better for repairs. It was necessary to pick one’s way as one went, and as the light was defective stumbles were not infrequent.

Our guide paused outside a door on the topmost landing. From some mysterious recess in her apparel she produced a key.

‘It’s in ’ere. I locked the door so that nothing mightn’t be disturbed. I knows ’ow particular you pleesmen is.’

She turned the key. We all went in—we, this time, in front, and she behind.

A candle was guttering on a broken and dilapidated single washhand stand. A small iron bedstead stood by its side, the clothes on which were all tumbled and tossed. There was a rush-seated chair with a hole in the seat,—and that, with the exception of one or two chipped pieces of stoneware, and a small round mirror which was hung on a nail against the wall, seemed to be all that the room contained. I could see nothing in the shape of a murdered man. Nor, it appeared, could the Inspector either.

‘What’s the meaning of this, Mrs Henderson? I don’t see anything here.’

‘It’s be’ind the bed, Mr Phillips. I left ’im just where I found ’im, I wouldn’t ’ave touched ’im not for nothing, nor yet ’ave let nobody else ’ave touched ’im neither, because, as I say, I know ’ow particular you pleesmen is.’

We all four went hastily forward. Atherton and I went to the head of the bed, Lessingham and the Inspector, leaning right across the bed, peeped over the side. There, on the floor in the space which was between the bed and the wall, lay the murdered man.

At sight of him an exclamation burst from Sydney’s lips.

‘It’s Holt!’

‘Thank God!’ cried Lessingham. ‘It isn’t Marjorie!’

The relief in his tone was unmistakable. That the one was gone was plainly nothing to him in comparison with the fact that the other was left.

Thrusting the bed more into the centre of the room I knelt down beside the man on the floor. A more deplorable spectacle than he presented I have seldom witnessed. He was decently clad in a grey tweed suit, white hat, collar and necktie, and it was perhaps that fact which made his extreme attenuation the more conspicuous. I doubt if there was an ounce of flesh on the whole of his body. His cheeks and the sockets of his eyes were hollow. The skin was drawn tightly over his cheek bones,—the bones themselves were staring through. Even his nose was wasted, so that nothing but a ridge of cartilage remained. I put my arm beneath his shoulder and raised him from the floor; no resistance was offered by the body’s gravity,—he was as light as a little child.

‘I doubt,’ I said, ‘if this man has been murdered. It looks to me like a case of starvation, or exhaustion,—possibly a combination of both.’

‘What’s that on his neck?’ asked the Inspector,—he was kneeling at my side.

He referred to two abrasions of the skin,—one on either side of the man’s neck.

‘They look to me like scratches. They seem pretty deep, but I don’t think they’re sufficient in themselves to cause death.’

‘They might be, joined to an already weakened constitution. Is there anything in his pockets?—let’s lift him on to the bed.’

We lifted him on to the bed,—a featherweight he was to lift. While the Inspector was examining his pockets—to find them empty—a tall man with a big black beard came bustling in. He proved to be Dr Glossop, the local police surgeon, who had been sent for before our quitting the Station House.

His first pronouncement, made as soon as he commenced his examination, was, under the circumstances, sufficiently startling.

‘I don’t believe the man’s dead. Why didn’t you send for me directly you found him?’

The question was put to Mrs Henderson.

‘Well, Dr Glossop, I wouldn’t touch ’im myself, and I wouldn’t ’ave ’im touched by no one else, because, as I’ve said afore, I know ’ow particular them pleesmen is.’

‘Then in that case, if he does die you’ll have had a hand in murdering him,—that’s all.’

The lady sniggered. ‘Of course Dr Glossop, we all knows that you’ll always ’ave your joke.’

‘You’ll find it a joke if you have to hang, as you ought to, you—’ The doctor said what he did say to himself, under his breath. I doubt if it was flattering to Mrs Henderson. ‘Have you got any brandy in the house?’

‘We’ve got everythink in the ’ouse for them as likes to pay for it,—everythink.’ Then, suddenly remembering that the police were present, and that hers were not exactly licensed premises, ‘Leastways we can send out for it for them parties as gives us the money, being, as is well known, always willing to oblige.’

‘Then send for some,—to the tap downstairs, if that’s the nearest! If this man dies before you’ve brought it I’ll have you locked up as sure as you’re a living woman.’

The arrival of the brandy was not long delayed,—but the man on the bed had regained consciousness before it came. Opening his eyes he looked up at the doctor bending over him.

‘Hollo, my man! that’s more like the time of day! How are you feeling?’

The patient stared hazily up at the doctor, as if his sense of perception was not yet completely restored,—as if this big bearded man was something altogether strange. Atherton bent down beside the doctor.

‘I’m glad to see you looking better, Mr Holt. You know me don’t you? I’ve been running about after you all day long.’

‘You are—you are—’ The man’s eyes closed, as if the effort at recollection exhausted him. He kept them closed as he continued to speak.

‘I know who you are. You are—the gentleman.’

‘Yes, that’s it, I’m the gentleman,—name of Atherton.—Miss Lindon’s friend. And I daresay you’re feeling pretty well done up, and in want of something to eat and drink,—here’s some brandy for you.’

The doctor had some in a tumbler. He raised the patient’s head, allowing it to trickle down his throat. The man swallowed it mechanically, motionless, as if unconscious what it was that he was doing. His cheeks flushed, the passing glow of colour caused their condition of extraordinary, and, indeed, extravagant attenuation, to be more prominent than ever. The doctor laid him back upon the bed, feeling his pulse with one hand, while he stood and regarded him in silence.

Then, turning to the Inspector, he said to him in an undertone;

‘If you want him to make a statement he’ll have to make it now, he’s going fast. You won’t be able to get much out of him,—he’s too far gone, and I shouldn’t bustle him, but get what you can.’

The Inspector came to the front, a notebook in his hand.

‘I understand

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)