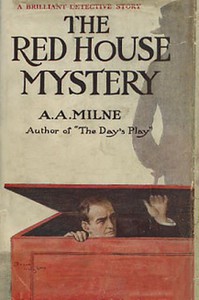

The Red House Mystery by A. A. Milne (bill gates best books TXT) 📖

- Author: A. A. Milne

Book online «The Red House Mystery by A. A. Milne (bill gates best books TXT) 📖». Author A. A. Milne

“You mean Mr. Robert,” said the second parlour-maid. She had been having a little nap in her room, but she had heard the bang. In fact, it had woken her up—just like something going off, it was.

“It was Mr. Mark’s voice,” said Elsie firmly.

“Pleading for mercy,” said an eager-eyed kitchen-maid hopefully from the door, and was hurried out again by the others, wishing that she had not given her presence away. But it was hard to listen in silence when she knew so well from her novelettes just what happened on these occasions.

“I shall have to give that girl a piece of my mind,” said Mrs. Stevens. “Well, Elsie?”

“He said, I heard him say it with my own ears, ‘It’s my turn now,’ he said, triumphant-like.”

“Well, if you think that’s a threat, dear, you’re very particular, I must say.”

But Audrey remembered Elsie’s words when she was in front of Inspector Birch. She gave her own evidence with the readiness of one who had already repeated it several times, and was examined and cross-examined by the Inspector with considerable skill. The temptation to say, “Never mind about what you said to him,” was strong, but he resisted it, knowing that in this way he would discover best what he said to her. By this time both his words and the looks he gave her were getting their full value from Audrey, but the general meaning of them seemed to be well-established.

“Then you didn’t see Mr. Mark at all.”

“No, sir; he must have come in before and gone up to his room. Or come in by the front door, likely enough, while I was going out by the back.”

“Yes. Well, I think that’s all that I want to know, thank you very much. Now what about the other servants?”

“Elsie heard the master and Mr. Robert talking together,” said Audrey eagerly. “He was saying—Mr. Mark, I mean—”

“Ah! Well, I think Elsie had better tell me that herself. Who is Elsie, by the way?”

“One of the housemaids. Shall I send her to you, sir?”

“Please.”

Elsie was not sorry to get the message. It interrupted a few remarks from Mrs. Stevens about Elsie’s conduct that afternoon which were (Elsie thought) much better interrupted. In Mrs. Stevens’ opinion any crime committed that afternoon in the office was as nothing to the double crime committed by the unhappy Elsie.

For Elsie realized too late that she would have done better to have said nothing about her presence in the hall that afternoon. She was bad at concealing the truth and Mrs. Stevens was good at discovering it. Elsie knew perfectly well that she had no business to come down the front stairs, and it was no excuse to say that she happened to come out of Miss Norris’ room just at the head of the stairs, and didn’t think it would matter, as there was nobody in the hall, and what was she doing anyhow in Miss Norris’ room at that time? Returning a magazine? Lent by Miss Norris, might she ask? Well, not exactly lent. Really, Elsie!—and this in a respectable house! In vain for poor Elsie to plead that a story by her favourite author was advertised on the cover, with a picture of the villain falling over the cliff. “That’s where you’ll go to, my girl, if you aren’t careful,” said Mrs. Stevens firmly.

But, of course, there was no need to confess all these crimes to Inspector Birch. All that interested him was that she was passing through the hall, and heard voices in the office.

“And stopped to listen?”

“Certainly not,” said Elsie with dignity, feeling that nobody really understood her. “I was just passing through the hall, just as you might have been yourself, and not supposing they was talking secrets, didn’t think to stop my ears, as no doubt I ought to have done.” And she sniffed slightly.

“Come, come,” said the Inspector soothingly, “I didn’t mean to suggest—”

“Everyone is very unkind to me,” said Elsie between sniffs, “and there’s that poor man lying dead there, and sorry they’d have been, if it had been me, to have spoken to me as they have done this day.”

“Nonsense, we’re going to be very proud of you. I shouldn’t be surprised if your evidence were of very great importance. Now then, what was it you heard? Try to remember the exact words.”

Something about working in a passage, thought Elsie.

“Yes, but who said it?”

“Mr. Robert.”

“How do you know it was Mr. Robert? Had you heard his voice before?”

“I don’t take it upon myself to say that I had had any acquaintance with Mr. Robert, but seeing that it wasn’t Mr. Mark, nor yet Mr. Cayley, nor any other of the gentlemen, and Miss Stevens had shown Mr. Robert into the office not five minutes before—”

“Quite so,” said the Inspector hurriedly. “Mr. Robert, undoubtedly. Working in a passage?”

“That was what it sounded like, sir.”

“H’m. Working a passage over—could that have been it?”

“That’s right, sir,” said Elsie eagerly. “He’d worked his passage over.”

“Well?”

“And then Mr. Mark said loudly—sort of triumphant-like—‘It’s my turn now. You wait.’”

“Triumphantly?”

“As much as to say his chance had come.”

“And that’s all you heard?”

“That’s all, sir—not standing there listening, but just passing through the hall, as it might be any time.”

“Yes. Well, that’s really very important, Elsie. Thank you.”

Elsie gave him a smile, and returned eagerly to the kitchen. She was ready for Mrs. Stevens or anybody now.

Meanwhile Antony had been exploring a little on his own. There was a point which was puzzling him. He went through the hall to the front of the house and stood at the open door, looking out on to the drive. He and Cayley had run round the house to the left. Surely it would have been quicker to have run round to the right? The front door was not in the middle of the house, it was to the end. Undoubtedly they went the longest way round. But perhaps there was something in the way, if one went to the right—a wall, say. He strolled off in that direction, followed a path round the house and came in sight of the office windows. Quite simple, and about half the distance of the other way. He went on a little farther, and came to a door, just beyond the broken-in windows. It opened easily, and he found himself in a passage. At the end of the passage was another door. He opened it and found himself in the hall again.

“And, of course, that’s the quickest way of the three,” he said to himself. “Through the hall, and out at the back; turn to the left and there you are. Instead of which, we ran the longest way round the house. Why? Was it to give Mark more time in which to escape? Only, in that case—why run? Also, how did Cayley know then that it was Mark who was trying to escape? If he had guessed—well, not guessed, but been afraid—that one had shot the other, it was much more likely that Robert had shot Mark. Indeed, he had admitted that this was what he thought. The first thing he had said when he turned the body over was, ‘Thank God! I was afraid it was Mark.’ But why should he want to give Robert time in which to get away? And again—why run, if he did want to give him time?”

Antony went out of the house again to the lawns at the back, and sat down on a bench in view of the office windows.

“Now then,” he said, “let’s go through Cayley’s mind carefully, and see what we get.”

Cayley had been in the hall when Robert was shown into the office. The servant goes off to look for Mark, and Cayley goes on with his book. Mark comes down the stairs, warns Cayley to stand by in case he is wanted, and goes to meet his brother. What does Cayley expect? Possibly that he won’t be wanted at all; possibly that his advice may be wanted in the matter, say, of paying Robert’s debts, or getting him a passage back to Australia; possibly that his physical assistance may be wanted to get an obstreperous Robert out of the house. Well, he sits there for a moment, and then goes into the library. Why not? He is still within reach, if wanted. Suddenly he hears a pistol-shot. A pistol-shot is the last noise you expect to hear in a country-house; very natural, then, that for the moment he would hardly realize what it was. He listens—and hears nothing more. Perhaps it wasn’t a pistol-shot after all. After a moment or two he goes to the library door again. The profound silence makes him uneasy now. Was it a pistol-shot? Absurd! Still—no harm in going into the office on some excuse, just to reassure himself. So he tries the door—and finds it locked!

What are his emotions now? Alarm, uncertainty. Something is happening. Incredible though it seems, it must have been a pistol-shot. He is banging at the door and calling out to Mark, and there is no answer. Alarm—yes. But alarm for whose safety? Mark’s, obviously. Robert is a stranger; Mark is an intimate friend. Robert has written a letter that morning, the letter of a man in a dangerous temper. Robert is the tough customer; Mark the highly civilized gentleman. If there has been a quarrel, it is Robert who has shot Mark. He bangs at the door again.

Of course, to Antony, coming suddenly upon this scene, Cayley’s conduct had seemed rather absurd, but then, just for the moment, Cayley had lost his head. Anybody else might have done the same. But, as soon as Antony suggested trying the windows, Cayley saw that that was the obvious thing to do. So he leads the way to the windows—the longest way.

Why? To give the murderer time to escape? If he had thought then that Mark was the murderer, perhaps, yes. But he thinks that Robert is the murderer. If he is not hiding anything, he must think so. Indeed he says so, when he sees the body; “I was afraid it was Mark,” he says, when he finds that it is Robert who is killed. No reason, then, for wishing to gain time. On the contrary, every instinct would urge him to get into the room as quickly as possible, and seize the wicked Robert. Yet he goes the longest way round. Why? And then, why run?

“That’s the question,” said Antony to himself, as he filled his pipe, “and bless me if I know the answer. It may be, of course, that Cayley is just a coward. He was in no hurry to get close to Robert’s revolver, and yet wanted me to think that he was bursting with eagerness. That would explain it, but then that makes Cayley out a coward. Is he? At any rate he pushed his face up against the window bravely enough. No, I want a better answer than that.”

He sat there with his unlit pipe in his hand, thinking. There were one or two other things in the back of his brain, waiting to be taken out and looked at. For the moment he left them undisturbed. They would come back to him later when he wanted them.

He laughed suddenly, and lit his pipe.

“I was wanting a new profession,” he thought, “and now I’ve found it. Antony Gillingham, our own private sleuthhound. I shall begin to-day.”

Whatever Antony Gillingham’s other qualifications for his new profession, he had at any rate a brain which worked clearly and quickly. And this clear brain of his had already told him that he was the only person in the house at that moment who was unhandicapped in the search for truth. The inspector had arrived in it to find a man dead and a man missing. It was extremely probable, no doubt, that the missing man had shot the dead man. But it was more than extremely probable, it was almost certain that the Inspector would start with the idea that this extremely probable solution was the one true solution, and that, in consequence, he would be less disposed to consider without prejudice any other solution. As regards

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)