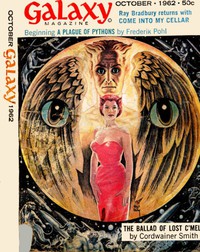

Plague of Pythons by Frederik Pohl (uplifting books for women .TXT) 📖

- Author: Frederik Pohl

Book online «Plague of Pythons by Frederik Pohl (uplifting books for women .TXT) 📖». Author Frederik Pohl

He could go no farther because he had nowhere to go. He had had two homes and he had been driven from both of them. He had had hope twice, and twice he had been damned.

He lay on his back, with the burning house mumbling and crackling in the distance, and stared up at the orange-lit tops of the trees and, past them, the stars. Over his left shoulder Deneb chased Vega across the sky; toward his feet something moved between the bright rosy dot that was Antares and another, the same brightness and hue—Mars? He spent several moments wondering if Mars were in that part of the heavens. Then he looked again for the tiny moving point that had crossed the claws of the Scorpion, but it was gone. A satellite, maybe. Although there were few of them left that the naked eye could hope to see. And there would never be any more, because the sort of accumulated wealth of nations that threw rockets into the sky was forever spent.

It was probably an airplane, he thought drowsily, and drifted off to sleep without realizing how remote even that possibility had become.... He woke up to find that he was getting to his feet.

Once again an interloper tenanted his brain. He tried to interfere, for he could not help it, although he knew how useless it was, but his own neck muscles turned his head from side to side, his own eyes looked this way and that, his own hand reached down for a dead branch that lay on the ground, then hesitated and withdrew. His body stood motionless for a second, the lips moving, the larynx mumbling to itself. He could almost hear words. Chandler felt like a fly in amber, prisoned in his own brainbox. He was not surprised when his legs moved to carry him back toward the destroyed building, now a fakir's bed of white-hot coals with brush fires spattered around it. He thought he knew why. It seemed very likely that what possessor had him was a sort of clean-up squad, tidying up the loose ends of the slaughter; he expected that his body's errand was to destroy itself, and thus him, as all the Orphalese had been destroyed.

V

Chandler's body carried him rapidly toward the house. Now and then it paused and glanced about. It seemed to be weighing some shortcut in its errand; but always it resumed its climb.

Chandler could sympathize with it, in a way. He still felt every pain from burn, brand and wound; as they neared the embers of the building the heat it threw off intensified them all. He could not be a comfortable body to inhabit for long. He was almost sympathetic because his tenant could not find a convenient weapon with which to fulfill his purpose.

When it seemed they could get no closer without the skin of his face crackling and bursting into flame his body halted.

Chandler could feel his muscles gathering for what would be the final leap into the auto-da-fe. His feet took a short step—and slipped. His body stumbled and recovered itself; his mouth swore thickly in a language he did not know.

Then his body hesitated, glanced at the ground, paused again and bent down. It had tripped on a book. It picked the book up, and Chandler saw that it was the Orphalese copy of Gibran's The Prophet.

Chandler's body stood poised for a moment, in an attitude of thought. Then it sat down, in the play of heat from the coals. It was a moment before Chandler realized he was free. He tested his legs; they worked; he got up, turned and began to walk away.

He had traveled no more than a few yards when he stumbled slightly, as though shifting gears, and felt the tenant in his mind again.

He continued to walk away from the building, down toward the road. Once his arm raised the book he still carried and his eyes glanced down, as if for reassurance that it was the same book. That was the only clue he was given as to what had happened and it was not much. It was as though his occupying power, whatever it was, had gone—somewhere—to think things over, perhaps to ask a question of an unimaginable companion, and then returned with an altered purpose. As time passed, Chandler began to receive additional clues, but he was in little shape to fit them together, for his body was near exhaustion.

He walked to the road, and waited, rigid, until a panel truck came bouncing along. He hailed it, his arms making a sign he did not understand, and when it stopped he addressed the driver in a language he did not speak. "Shto," said the driver, a somber-faced Mexican in dungarees. "Ja nie jestem Ruska. Czego pragniesh?"

"Czy ty jedziesz to Los Angeles?" asked Chandler's mouth.

"Nyet. Acapulco."

Chandler's voice argued, "Wes na Los Angeles."

"Nyet." The voices droned on. Chandler lost interest in the argument and was only relieved when it seemed somehow to be settled and he was herded into the back of the truck. The somber Mexican locked him in; he felt the truck begin to move; his tenant left him, and he was at once asleep.

He woke long enough to find himself standing in the mist of early dawn at a crossroads. In a few minutes another car came by, and his voice talked earnestly with the driver for a moment. Chandler got in, was released, slept again and woke to find himself free and abandoned, sprawled across the back seat of the car, which was parked in front of a building marked Los Angeles International Airport.

Chandler got out of the car and strolled around, stretching. He realized he was very hungry.

No one was in sight. The field showed clear signs of having been through the same sort of destruction that had visited every major communications facility in the world. Part of the building before him was smashed flat and showed signs of having been burned. He saw projecting aluminum members, twisted and scorched but still visibly aircraft parts. Apparently a transport had crashed into the building. Burned-out cars littered the parking lot and what had once been a green lawn. They seemed to have been bulldozed out of the way, but not an inch farther than was necessary to clear the approach roads.

To his right, as he stared out onto the field, was a strange-looking construction on three legs, several stories high. It did not seem to serve any useful purpose. Perhaps it had been a sort of luxury restaurant at one time, like the Space Needle from the old Seattle Fair, but now it too was burned out and glassless in its windows. The field itself was swept bare except for two or three parked planes in the bays, but he could see wrecked transports lining the approach strips. All in all, Los Angeles International Airport appeared to be serviceable, but only just.

He wondered where all the people were.

Distant truck noises answered part of the question. An Army six by six came bumping across a bridge that led from the takeoff strips to this parking area of the airport. Five men got out next to one of the ships. They glanced at him but did not speak as they began loading crates of some sort of goods from the truck into the aircraft, a four-engine, swept-wing jet of what looked to Chandler like an obsolete model. Perhaps it was one of the early Boeings. There hadn't been many of those in use at the time the troubles began, too big and fast for short hops, too slow to compete over long distances with the rockets. But, of course, with all the destruction, and with no new aircraft being built anywhere in the world any more, no doubt they were as good as could be found.

The truckmen did not seem to be possessed; they worked with the normal amount of grunting and swearing, pausing to wipe sweat away or to scratch an itch. They showed neither the intense malevolent concentration nor the wide-eyed idiot curiosity of those whose bodies were no longer their own. Chandler settled the woolen cap over the brand on his forehead, to avoid unpleasantness, and drifted over toward them.

They stopped work and regarded him. One of them said something to another, who nodded and walked toward Chandler. "What do you want?" he demanded warily.

"I don't know. I was going to ask you the same question, I guess."

The man scowled. "Didn't your exec tell you what to do?"

"My what?"

The man paused, scratched and shook his head. "Well, stay away from us. This is an important shipment, see? I guess you're all right or you couldn't've got past the guards, but I don't want you messing us up. Got enough trouble already. I don't know why," he said in the tones of an old grievance, "we can't get the execs to let us know when they're going to bring somebody in. It wouldn't hurt them! Now here we got to load and fuel this ship and, for all I know, you've got half a ton of junk around somewhere that you're going to load onto it. How do I know how much fuel it'll take? No weather, naturally. So if there's headwinds it'll take full tanks, but if there's extra cargo I—"

"The only cargo I brought with me that I can think of is a book," said Chandler. "Weighs maybe a pound. You think I'm supposed to get on that plane?"

The man grunted non-committally.

"All right, suit yourself. Listen, is there any place I can get something to eat?"

The man considered. "Well, I guess we can spare you a sandwich. But you wait here. I'll bring it to you."

He went back to the truck. A moment later one of the others brought Chandler two cold hamburgers wrapped in waxed paper, but would answer no questions.

Chandler ate every crumb, sought and found a washroom in the wrecked building, came out again and sat in the sun, watching the loading crew. He had become quite a fatalist. It did not seem that it was intended he should die immediately, so he might as well live.

There were large gaps in his understanding, but it seemed clear to Chandler that these men, though not possessed, were in some way working for the possessors. It was a distasteful concept; but on second thought it had reassuring elements. It was evidence that whatever the "execs" were, they were very possibly human beings—or, if not precisely human, at least shared the human trait of working by some sort of organized effort toward some sort of a goal. It was the first non-random phenomenon he had seen in connection with the possessors, barring the short-term tactical matters of mass slaughter and destruction. It made him feel—what he tried at once to suppress, for he feared another destroying frustration—a touch of hope.

The men finished their work but did not leave. Nor did they approach Chandler, but sat in the shade of their truck, waiting for something. He drowsed and was awakened by a distant sputter of a single-engined Aerocoupe that hopped across the building behind him, turned sharply and came down with a brisk little run in the parking bay itself.

From one side the pilot climbed down and from the other two men lifted, with great care, a wooden crate, small but apparently heavy. They stowed it in the jet while the pilot stood watching; then the pilot and one of the other men got into the crew compartment. Chandler could not be sure, but he had the impression that the truckman who entered the plane was no longer his own master. His movements seemed more sure and confident, but above all it was the mute, angry eyes with which his fellows regarded him that gave Chandler grounds for suspicion. He had no time to worry about that; for in the same breath he felt himself occupied once more.

He did not rise. His own voice said to him, "You. Votever you name, you fellow vit de book! You go get de book verever you pud it and get on dat ship dere, you see?" His eyes turned toward the waiting aircraft. "And don't forget de book!"

He was released. "I won't," he said automatically, and then realized that there was no longer anyone there to hear his answer.

When he retrieved the Gibran volume from the car and approached the plane the loading crew said nothing. Evidently they knew what he was doing—either because they too had been given instructions, or because they were used to such things. He paused at the wheeled stairs. "Listen," he said, "can you at least tell me where I'm going?"

The four remaining men looked at him silently, with the same angry, worried expression he

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)