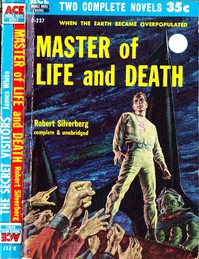

Master of Life and Death by Robert Silverberg (best fiction books to read .TXT) 📖

- Author: Robert Silverberg

Book online «Master of Life and Death by Robert Silverberg (best fiction books to read .TXT) 📖». Author Robert Silverberg

Hurriedly he gathered up the space-flight documents and jammed them in a file drawer near the data on terraforming. He surveyed his office; it looked neat, presentable. Glancing around, he made sure no stray documents were visible, documents which might reveal the truth about the space drive.

"Send in Dr. Lamarre," he said.

Dr. Lamarre was a short, thin, pale individual, with an uncertain wave in his sandy hair and a slight stoop of his shoulders. He carried a large, black leather portfolio which seemed on the point of exploding.

"Mr. Walton?"

"That's right. You're Dr. Lamarre?"

The small man handed him an engraved business card.

T. ELLIOT LAMARRE

Gerontologist

Walton fingered the card uneasily and returned it to its owner. "Gerontologist? One who studies ways of increasing the human life-span?"

"Precisely."

Walton frowned. "I presume you've had some previous dealings with the late Director FitzMaugham?"

Lamarre gaped. "You mean he didn't tell you?"

"Director FitzMaugham shared very little information with his assistants, Dr. Lamarre. The suddenness of my elevation to this post gave me little time to explore his files. Would you mind filling me in on the background?"

"Of course." Lamarre crossed his legs and squinted myopically across the desk at Walton. "To be brief, Mr. FitzMaugham first heard of my work fourteen years ago. Since that time, he's supported my experiments with private grants of his own, public appropriations whenever possible, and lately with money supplied by Popeek. Naturally, because of the nature of my work I've shunned publicity. I completed my final tests last week, and was to have seen the director yesterday. But—"

"I know. I was busy going through Mr. FitzMaugham's files when you called yesterday. I didn't have time to see anyone." Walton wished he had checked on this man Lamarre earlier. Apparently it was a private project of FitzMaugham's and of some importance.

"May I ask what this 'work' of yours consists of?"

"Certainly. Mr. FitzMaugham expressed a hope that someday man's life span might be infinitely extended. I'm happy to report that I have developed a simple technique which will provide just that." The little man smiled in self-satisfaction. "In short," he said, "what I have developed, in everyday terms, is immortality, Mr. Walton."

VIIIWalton was becoming hardened to astonishment; the further he excavated into the late director's affairs, the less susceptible he was to the visceral reaction of shock.

Still, this stunned him for a moment.

"Did you say you'd perfected this technique?" he asked slowly. "Or that it was still in the planning stage?"

Lamarre tapped the thick, glossy black portfolio. "In here. I've got it all." He seemed ready to burst with self-satisfaction.

Walton leaned back, spread his fingers against the surface of the desk, and wrinkled his forehead. "I've had this job since 1300 on the tenth, Mr. Lamarre. That's exactly two days ago, minus half an hour. And in that time I don't think I've had less than ten major shocks and half a dozen minor ones."

"Sir?"

"What I'm getting at is this: just why did Director FitzMaugham sponsor this project of yours?"

Lamarre looked blank. "Because the director was a great humanitarian, of course. Because he felt that the human life was short, far too short, and he wished his fellow men to enjoy long life. What other reason should there be?"

"I know FitzMaugham was a great man ... I was his secretary for three years." (Though he never said a word about you, Dr. Lamarre, Walton thought.) "But to develop immortality at this stage of man's existence...." Walton shook his head. "Tell me about your work, Dr. Lamarre."

"It's difficult to sum up readily. I've fought degeneration of the body on the cellular level, and my tests show a successful outcome. Phagocyte stimulation combined with—the data's all here, Mr. Walton. I needn't run through it for you."

He began to hunt in the portfolio, fumbling for something. After a moment he extracted a folded quarto sheet, spread it out, and nudged it across the desk toward Walton.

The director glanced at the sheet; it was covered with chemical equations. "Spare me the technical details, Dr. Lamarre. Have you tested your treatment yet?"

"With the only test possible, the test of time. There are insects in my laboratories that have lived five years or more—veritable Methuselahs of their genera. Immortality is not something one can test in less than infinite time. But beneath the microscope, one can see the cells regenerating, one can see decay combated...."

Walton took a deep breath. "Are you aware, Dr. Lamarre, that for the benefit of humanity I really should have you shot at once?"

"What?"

Walton nearly burst out laughing; the man looked outrageously funny with that look of shocked incomprehension on his face. "Do you understand what immortality would do to Earth?" he asked. "With no other planet of the solar system habitable by man, and none of the stars within reach? Within a generation we'd be living ten to the square inch. We'd—"

"Director FitzMaugham was aware of these things," Lamarre interrupted sharply. "He had no intention of administering my discovery wholesale to the populace. What's more, he was fully confident that a faster-than-light space drive would soon let us reach the planets, and that the terraforming engineers would succeed with their work on Venus."

"Those two factors are still unknowns in the equation," Walton said. "Neither has succeeded, as of now. And we can't possibly let word of your discovery get out until there are avenues to handle the overflow of population already on hand."

"So you propose—"

"To confiscate the notes you have with you, and to insist that you remain silent about this serum of yours until I give you permission to announce it."

"And if I refuse?"

Walton spread his hands. "Dr. Lamarre, I'm a reasonable man trying to do a very hard job. You're a scientist—and a sane one, I hope. I'd appreciate your cooperation. Bear with me a few weeks, and then perhaps the situation will change."

Awkward silence followed. Finally Lamarre said, "Very well. If you'll return my notes, I promise to keep silent until you give me permission to speak."

"That won't be enough. I'll need to keep the notes."

Lamarre sighed. "If you insist," he said.

When he was again alone, Walton stored the thick portfolio in a file drawer and stared at it quizzically.

FitzMaugham, he thought, you were incredible!

Lamarre's immortality serum, or whatever it was, was deadly. Whether it actually worked or not was irrelevant. If word ever escaped that an immortality drug existed, there would be rioting and death on a vast scale.

FitzMaugham had certainly seen that, and yet he had sublimely underwritten development of the serum, knowing that if terraforming and the ultradrive project should fail, Lamarre's project represented a major threat to civilization.

Well, Lamarre had knuckled under to Walton willingly enough. The problem now was to contact Lang on Venus and find out what was happening up there....

"Mr. Walton," said the annunciator. "There's a coded message arriving for Director FitzMaugham."

"Where from?"

"From space, sir. They say they have news, but they won't give it to anyone but Mr. FitzMaugham."

Walton cursed. "Where is this message being received?"

"Floor twenty-three, sir. Communications."

"Tell them I'll be right down," Walton snapped.

He caught a lift tube and arrived on the twenty-third floor moments later. No sooner had the tube door opened than he sprang out, dodging around a pair of startled technicians, and sprinted down the corridor toward communications.

Here throbbed the network that held the branches of Popeek together. From here the screens were powered, the annunciators were linked, the phones connected.

Walton pushed open a door marked Communications Central and confronted four busy engineers who were crowded around a complex receiving mechanism.

"Where's that space message?" he demanded of the sallow young engineer who approached him.

"Still coming in, sir. They're repeating it over and over. We're triangulating their position now. Somewhere near the orbit of Pluto, Mr. Walton."

"Devil with that. Where's the message?"

Someone handed him a slip of paper. It said, Calling Earth. Urgent call, top urgency, crash urgency. Will communicate only with D. F. FitzMaugham.

"This all it is?" Walton asked. "No signature, no ship name?"

"That's right, Mr. Walton."

"Okay. Find them in a hurry and send them a return message. Tell them FitzMaugham's dead and I'm his successor. Mention me by name."

"Yes, sir."

He stamped impatiently around the lab while they set to work beaming the message into the void. Space communication was a field that dazzled and bewildered Walton, and he watched in awe as they swung into operation.

Time passed. "You know of any ships supposed to be in that sector?" he asked someone.

"No, sir. We weren't expecting any calls except from Lang on Venus—" The technician gasped, realizing he had made a slip, and turned pale.

"That's all right," Walton assured him. "I'm the director, remember? I know all about Lang."

"Of course, sir."

"Here's a reply, sir," another of the nameless, faceless technicians said. Walton scanned it.

It read, Hello Walton. Request further identification before we report. McL.

A little shudder of satisfaction shook Walton at the sight of the initialed McL. at the end of the message. That could mean only McLeod—and that could mean only one thing: the experimental starship had returned!

Walton realized depressedly that this probably implied that they hadn't found any Earth-type worlds among the stars. McLeod's note to FitzMaugham had said they would search for a year, and would return home at the end of that time if they had no success. And just about a year had elapsed.

He said, "Send this return message: McLeod, Nairobi, X-72. Congratulations! Walton."

The technician vanished again, leaving Walton alone. He gazed moodily at the complex maze of equipment all around him, listened to the steady tick-tick of the communication devices, strained his ears to pick up fragments of conversation from the men.

After what seemed like an hour, the technician returned. "There's a message coming through now, sir. We're decoding it as fast as we can."

"Make it snappy," Walton said. His watch read 1429. Only twenty minutes had passed since he had gone down there.

A grimy sheet of paper was thrust under his nose. He read it:

Hello Walton, this is McLeod. Happy to report that experimental ship X-72 is returning home with all hands in good shape, after a remarkable one-year cruise of the galaxy. I feel like Ulysses returning to Ithaca, except we didn't have such a hard time of it.

I imagine you'll be interested in this: we found a perfectly lovely and livable world in the Procyon system. No intelligent life at all, and incredibly fine climate. Pity old FitzMaugham couldn't have lived to hear about it. Be seeing you soon. McLeod.

Walton's hands were still shaking as he pressed the actuator that would let him back into his office. He would have to call another meeting of the section chiefs again, to discuss the best method of presenting this exciting news to the world.

For one thing, they would have to explain away FitzMaugham's failure to reveal that the X-72 had been sent out over a year ago. That could be easily handled.

Then, there would have to be a careful build-up: descriptions of the new world, profiles of the heroes who had found it, etcetera. Someone was going to have to work out a plan for emigration ... unless the resourceful FitzMaugham had already drawn up such a plan and stowed it in Files for just this anticipated day.

And then, perhaps Lamarre could be called back now, and allowed to release his discovery. Plans buzzed in Walton's mind: in the event that people proved reluctant to leave Earth and conquer an unknown world, no matter how tempting the climate, it might be feasible to dangle immortality before them—to restrict Lamarre's treatment to volunteer colonists, or something along that line. There was plenty of time to figure that out, Walton thought.

He stepped into his office and locked the door behind him. A glow of pleasure surrounded him; for once it seemed that things were heading in the right direction. He was happy, in a way, that FitzMaugham was no longer in charge. Now, with mankind on the threshold of—

Walton blinked. Did I leave that file drawer open when I left the office? he wondered. He was usually more cautious than that.

The file was definitely open now, as were the two cabinets adjoining it. Numbly he swung the cabinet doors wider, peered into the shadows, groped inside.

The drawers containing the documents pertaining to terraforming and to McLeod's space drive seemed intact. But the cabinet in which Walton had placed Lamarre's portfolio—that cabinet was totally empty!

Someone's been in here, he thought angrily. And then the anger changed to agony as he remembered what had been in Lamarre's portfolio, and what would happen if that formula were loosed indiscriminately in the world.

IXThe odd part of it, Walton thought, was that there was absolutely nothing he could do.

He could call Sellors and give him a roasting for not guarding his office properly, but that wouldn't restore the missing portfolio.

He could send out a general

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)