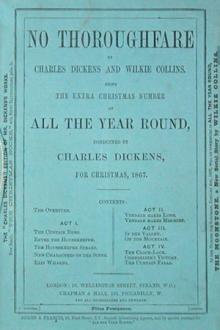

No Thoroughfare by Wilkie Collins (interesting books to read TXT) 📖

- Author: Wilkie Collins

- Performer: -

Book online «No Thoroughfare by Wilkie Collins (interesting books to read TXT) 📖». Author Wilkie Collins

“Countrymen,” he explained, as he attended Vendale to the door. “Poor compatriots. Grateful and attached, like dogs! Good-bye. To meet again. So glad!”

Two more light touches on his elbows dismissed him into the street.

Sweet Marguerite at her frame, and Madame Dor’s broad back at her telegraph, floated before him to Cripple Corner. On his arrival there, Wilding was closeted with Bintrey. The cellar doors happening to be open, Vendale lighted a candle in a cleft stick, and went down for a cellarous stroll. Graceful Marguerite floated before him faithfully, but Madame Dor’s broad back remained outside.

The vaults were very spacious, and very old. There had been a stone crypt down there, when bygones were not bygones; some said, part of a monkish refectory; some said, of a chapel; some said, of a Pagan temple. It was all one now. Let who would make what he liked of a crumbled pillar and a broken arch or so. Old Time had made what HE liked of it, and was quite indifferent to contradiction.

The close air, the musty smell, and the thunderous rumbling in the streets above, as being, out of the routine of ordinary life, went well enough with the picture of pretty Marguerite holding her own against those two. So Vendale went on until, at a turning in the vaults, he saw a light like the light he carried.

“O! You are here, are you, Joey?”

“Oughtn’t it rather to go, ‘O! YOU’RE here, are you, Master George?’ For it’s my business to be here. But it ain’t yourn.”

“Don’t grumble, Joey.”

“O! I don’t grumble,” returned the Cellarman. “If anything grumbles, it’s what I’ve took in through the pores; it ain’t me. Have a care as something in you don’t begin a grumbling, Master George. Stop here long enough for the wapours to work, and they’ll be at it.”

His present occupation consisted of poking his head into the bins, making measurements and mental calculations, and entering them in a rhinoceros-hide-looking note-book, like a piece of himself.

“They’ll be at it,” he resumed, laying the wooden rod that he measured with across two casks, entering his last calculation, and straightening his back, “trust ‘em! And so you’ve regularly come into the business, Master George?”

“Regularly. I hope you don’t object, Joey?”

“I don’t, bless you. But Wapours objects that you’re too young. You’re both on you too young.”

“We shall got over that objection day by day, Joey.”

“Ay, Master George; but I shall day by day get over the objection that I’m too old, and so I shan’t be capable of seeing much improvement in you.”

The retort so tickled Joey Ladle that he grunted forth a laugh and delivered it again, grunting forth another laugh after the second edition of “improvement in you.”

“But what’s no laughing matter, Master George,” he resumed, straightening his back once more, “is, that young Master Wilding has gone and changed the luck. Mark my words. He has changed the luck, and he’ll find it out. I ain’t been down here all my life for nothing! I know by what I notices down here, when it’s a-going to rain, when it’s a-going to hold up, when it’s a-going to blow, when it’s a-going to be calm. I know, by what I notices down here, when the luck’s changed, quite as well.”

“Has this growth on the roof anything to do with your divination?” asked Vendale, holding his light towards a gloomy ragged growth of dark fungus, pendent from the arches with a very disagreeable and repellent effect. “We are famous for this growth in this vault, aren’t we?”

“We are Master George,” replied Joey Ladle, moving a step or two away, “and if you’ll be advised by me, you’ll let it alone.”

Taking up the rod just now laid across the two casks, and faintly moving the languid fungus with it, Vendale asked, “Ay, indeed? Why so?”

“Why, not so much because it rises from the casks of wine, and may leave you to judge what sort of stuff a Cellarman takes into himself when he walks in the same all the days of his life, nor yet so much because at a stage of its growth it’s maggots, and you’ll fetch ‘em down upon you,” returned Joey Ladle, still keeping away, “as for another reason, Master George.”

“What other reason?”

“(I wouldn’t keep on touchin’ it, if I was you, sir.) I’ll tell you if you’ll come out of the place. First, take a look at its colour, Master George.”

“I am doing so.”

“Done, sir. Now, come out of the place.”

He moved away with his light, and Vendale followed with his. When Vendale came up with him, and they were going back together, Vendale, eyeing him as they walked through the arches, said: “Well, Joey? The colour.”

“Is it like clotted blood, Master George?”

“Like enough, perhaps.”

“More than enough, I think,” muttered Joey Ladle, shaking his head solemnly.

“Well, say it is like; say it is exactly like. What then?”

“Master George, they do say—”

“Who?”

“How should I know who?” rejoined the Cellarman, apparently much exasperated by the unreasonable nature of the question. “Them! Them as says pretty well everything, you know. How should I know who They are, if you don’t?”

“True. Go on.”

“They do say that the man that gets by any accident a piece of that dark growth right upon his breast, will, for sure and certain, die by murder.”

As Vendale laughingly stopped to meet the Cellarman’s eyes, which he had fastened on his light while dreamily saying those words, he suddenly became conscious of being struck upon his own breast by a heavy hand. Instantly following with his eyes the action of the hand that struck him—which was his companion’s—he saw that it had beaten off his breast a web or clot of the fungus even then floating to the ground.

For a moment he turned upon the Cellarman almost as scared a look as the Cellarman turned upon him. But in another moment they had reached the daylight at the foot of the cellar-steps, and before he cheerfully sprang up them, he blew out his candle and the superstition together.

EXIT WILDINGOn the morning of the next day, Wilding went out alone, after leaving a message with his clerk. “If Mr. Vendale should ask for me,” he said, “or if Mr. Bintrey should call, tell them I am gone to the Foundling.” All that his partner had said to him, all that his lawyer, following on the same side, could urge, had left him persisting unshaken in his own point of view. To find the lost man, whose place he had usurped, was now the paramount interest of his life, and to inquire at the Foundling was plainly to take the first step in the direction of discovery. To the Foundling, accordingly, the wine-merchant now went.

The once familiar aspect of the building was altered to him, as the look of the portrait over the chimney-piece was altered to him. His one dearest association with the place which had sheltered his childhood had been broken away from it for ever. A strange reluctance possessed him, when he stated his business at the door. His heart ached as he sat alone in the waiting-room while the Treasurer of the institution was being sent for to see him. When the interview began, it was only by a painful effort that he could compose himself sufficiently to mention the nature of his errand.

The Treasurer listened with a face which promised all needful attention, and promised nothing more.

“We are obliged to be cautious,” he said, when it came to his turn to speak, “about all inquiries which are made by strangers.”

“You can hardly consider me a stranger,” answered Wilding, simply. “I was one of your poor lost children here, in the bygone time.”

The Treasurer politely rejoined that this circumstance inspired him with a special interest in his visitor. But he pressed, nevertheless for that visitor’s motive in making his inquiry. Without further preface, Wilding told him his motive, suppressing nothing. The Treasurer rose, and led the way into the room in which the registers of the institution were kept. “All the information which our books can give is heartily at your service,” he said. “After the time that has elapsed, I am afraid it is the only information we have to offer you.”

The books were consulted, and the entry was found expressed as follows:

“3d March, 1836. Adopted, and removed from the Foundling Hospital, a male infant, named Walter Wilding. Name and condition of the person adopting the child—Mrs. Jane Ann Miller, widow. Address— Lime-Tree Lodge, Groombridge Wells. References—the Reverend John Harker, Groombridge Wells; and Messrs. Giles, Jeremie, and Giles, bankers, Lombard Street.”

“Is that all?” asked the wine-merchant. “Had you no after-communication with Mrs. Miller?”

“None—or some reference to it must have appeared in this book.”

“May I take a copy of the entry?”

“Certainly! You are a little agitated. Let me make a copy for you.”

“My only chance, I suppose,” said Wilding, looking sadly at the copy, “is to inquire at Mrs. Miller’s residence, and to try if her references can help me?”

“That is the only chance I see at present,” answered the Treasurer. “I heartily wish I could have been of some further assistance to you.”

With those farewell words to comfort him Wilding set forth on the journey of investigation which began from the Foundling doors. The first stage to make for, was plainly the house of business of the bankers in Lombard Street. Two of the partners in the firm were inaccessible to chance-visitors when he asked for them. The third, after raising certain inevitable difficulties, consented to let a clerk examine the ledger marked with the initial letter “M.” The account of Mrs. Miller, widow, of Groombridge Wells, was found. Two long lines, in faded ink, were drawn across it; and at the bottom of the page there appeared this note Account closed, September 30th,

1837.”

So the first stage of the journey was reached—and so it ended in No Thoroughfare! After sending a note to Cripple Corner to inform his partner that his absence might be prolonged for some hours, Wilding took his place in the train, and started for the second stage on the journey—Mrs. Miller’s residence at Groombridge Wells.

Mothers and children travelled with him; mothers and children met each other at the station; mothers and children were in the shops when he entered them to inquire for Lime-Tree Lodge. Everywhere, the nearest and dearest of human relations showed itself happily in the happy light of day. Everywhere, he was reminded of the treasured delusion from which he had been awakened so cruelly—of the lost memory which had passed from him like a reflection from a glass.

Inquiring here, inquiring there, he could hear of no such place as Lime-Tree Lodge. Passing a house-agent’s office, he went in wearily, and put the question for the last time. The house-agent pointed across the street to a dreary mansion of many windows, which might have been a manufactory, but which was an hotel. “That’s where Lime-Tree Lodge stood, sir,” said the man, “ten years ago.”

The second stage reached, and No Thoroughfare again!

But one chance was left. The clerical reference, Mr. Harker, still remained to be found. Customers coming in at the moment to occupy the house-agent’s attention, Wilding went down the

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)