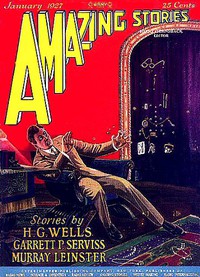

The Red Dust by Murray Leinster (free children's ebooks pdf .TXT) 📖

- Author: Murray Leinster

Book online «The Red Dust by Murray Leinster (free children's ebooks pdf .TXT) 📖». Author Murray Leinster

Burl stood still, drooping in discouragement upon his spear, the feathery moth's antenn� bound upon his forehead shadowed darkly against the graying sky. Soon the mushrooms would begin to burst—

Then, suddenly, he lifted his head, encouragement and delight upon his features. He had heard the ripple of running water. His followers looked at him with dawning hope. Without a word, Burl began to run, and they followed him more slowly. His voice came back to them in a shout of delight.

Then they, too, broke into a jog-trot. In a moment they had emerged from the thick tangle of brownish-red stalks and were upon the banks of a wide and swiftly running river, the same river whose gleam Burl had caught the day before from the farther side of the mushroom forest.

Once before Burl had floated down a river upon a mushroom raft. Then his journey had been involuntary and unlooked for. He had been carried far from his tribe and far from Saya, and his heart had been filled with desolation.

Now he viewed the swiftly running current with eager delight. He cast his eyes up and down the bank. Here and there the river-bank rose in a low bluff, and thick shelf-growths stretched out above the water.

Burl was busy in an instant, stabbing the hard growths with his spear and striving to wrench them free. The tribesmen stared at him, uncomprehending, but at an order from him they did likewise.

Soon a dozen thick masses of firm, light fungus lay upon the shore where it shelved gently into the water. Burl began to explain what they were to do, but one or two of the men dared remonstrate, saying humbly that they were afraid to part from him. If they might embark upon the same thing with him, they would be safe, but otherwise they were afraid.

Burl cast an apprehensive glance at the sky. Day was coming rapidly on. Soon the red mushrooms would begin to shoot their columns of deadly dust into the air. This was no time to pause and deliberate. Then Saya spoke softly.

Burl listened, and made a mighty sacrifice. He took his gorgeous velvet cloak from his shoulders—it was made from the wing of a great moth—and tore it into a dozen long, irregular pieces, tearing it along the lines of the sinews that reinforced it. He planted his spear upright in the largest piece of shelf-fungus and caused his followers to do likewise, then fastened the strips of sinew and velvet to his spear-shaft, and ordered them to do the same to the other spears.

In a matter of minutes the dozen tiny rafts were bobbing on the water, clustered about the larger, central bit. Then, one by one, the tribefolk took their places, and Burl shoved off.

The agglomeration of cranky, unseaworthy bits of shelf-fungus moved slowly out from the shore until the current caught it. Burl and Saya sat upon the central bit, with the other trustful but somewhat frightened pink-skinned people all about them. And, as they began to move between the mushroom-lined banks of the river and the mist of the night began to lift from its surface, far in the interior of the forest of the red fungoids a column of sullen red leaped into the air. The first of the malignant growths had cast its cargo of poisonous dust into the still-humid atmosphere.

The conelike column spread out and grew thin, but even after it had sunk into the earth, a reddish taint remained in the air about the place where it had been. The deadly red haze that hung all through the day over the red forest was in process of formation.

But by that time the unstable fungus rafts were far down the river, bobbing and twirling in the current, with the wide-eyed people upon them gazing in wonderment at the shores as they glided by. The red mushrooms grew less numerous upon the banks. Other growths took their places. Molds and rusts covered the ground as grass had done in ages past. Mushrooms showed their creamy, rounded heads. Malformed things with swollen trunks and branches in strange mockery of the trees they had superseded made their appearance, and once the tribesmen saw the dark bulk of a hunting spider outlined for a moment upon the bank.

All the long day they rode upon the current, while the insect life that had been absent in the neighborhood of the forest of death made its appearance again. Bees once more droned overhead, and wasps and dragon-flies. Four-inch mosquitoes made their appearance, to be fought off by the tribefolk with lusty blows, and glittering beetles and shining flies, whose bodies glittered with a metallic luster, buzzed and flew above the water.

Huge butterflies once more were seen, dancing above the steaming, festering earth in an apparent ecstasy from the mere fact of existence, and all the thousand and one forms of insect life that flew and crawled, and swam and dived, showed themselves to the tribesmen on the raft.

Water-beetles came lazily to the surface, to snap with sudden energy at mosquitoes busily laying their eggs in the nearly stagnant water by the river-banks. Burl pointed out to Saya, with some excitement, their silver breast-plates that shone as they darted under the water again. And the shell-covered boats of a thousand caddis-worms floated in the eddies and back-waters of the stream. Water-boatmen and whirligigs—almost alone among insects in not having shared in the general increase of size—danced upon the oily waves.

The day wore on as the shores flowed by. The tribefolk ate of their burdens of mushroom and meat, and drank from the fresh water of the river. Then, when afternoon came, the character of the country about the stream changed. The banks fell away, and the current slackened. The shores became indefinite, and the river merged itself into a swamp, a vast swamp from which a continual muttering came which the tribesmen heard for a long time before they saw the swamp itself.

The water seemed to turn dark, as black mud took the place of the clay that had formed its bed, and slowly, here and there, then more frequently, floating green things that were stationary, and did not move with the current, appeared. They were the leaves of water-lilies, that had remained with the giant cabbages and a very few other plants in the midst of a fungoid world. The green leaves were twelve feet across, and any one of them would have floated the whole of Burl's tribe.

Presently they grew numerous so that the channel was made narrow, and the mushroom rafts passed between rows of the great leaves, with here and there a colossal, waxen blossom in which three men might have hidden and which exhaled an almost over-powering fragrance into the air.

And the muttering that had been heard far away grew in volume to an intermittent, incredibly deep bass roar. It seemed to come from the banks on either side, and actually was the discordant croaking of the giant frogs, grown to eight feet in length, which lived and loved in the huge swamp, above which golden butterflies danced in ecstasy, and which the transcendently beautiful blossoms of the water-lilies filled with fragrance.

The swamp was a place of riotous life. The green bodies of the colossal frogs—perched upon the banks in strange immobility and only opening their huge mouths to emit their thunderous croakings—the green bodies of the frogs blended queerly with the vivid color of the water-lily leaves. Dragon-flies fluttered in their swift and angular flight above the black and reeking mud. Green-bottles and blue-bottles and a hundred other species of flies buzzed busily in the misty air, now and then falling prey to the licking tongues of the frogs.

Bees droned overhead in flight less preoccupied and worried than elsewhere flitting from blossom to blossom of the tremendous water-lilies, loading their crops with honey and the bristles of their legs with yellow pollen.

Everywhere over the mushroom-covered world the air was never quite free from mist, and the steaming exhalations of the pools, but here in the swamps the atmosphere was so heavily laden with moisture that the bodies of the tribefolk were covered with glistening droplets, while the wide, flat water-lily leaves glittered like platters of jewels from the "steam" that had condensed upon their upper surfaces.

The air was full of shining bodies and iridescent wings. Myriads of tiny midges—no more than three or four inches across their wings—danced above the slow-flowing water. And butterflies of every imaginable shade and color, from the most delicate lavender to the most vivid carmine, danced and fluttered, alighting upon the white water-lilies to sip daintily of their nectar, skimming the surface of the water, enamored of their brightly tinted reflections.

And the pink-skinned tribesfolk, floating through this fairyland on their mushroom rafts, gazed with wide eyes at the beauty about them, and drew in great breaths of the intoxicating fragrance of the great white flowers that floated like elfin boats upon the dark water.

CHAPTER V Out of BondageThe mist was heavy and thick, and through it the flying creatures darted upon their innumerable businesses, visible for an instant in all their colorful beauty, then melting slowly into indefiniteness as they sped away. The tribefolk on the clustered rafts watched them as they darted overhead, and for hours the little squadron of fungoid vessels floated slowly through the central channel of the marsh.

The river had split into innumerable currents which meandered purposelessly through the glistening black mud of the swamp, but after a long time they seemed to reassemble, and Burl could see what had caused the vast morass.

Hills appeared on either side of the stream, which grew higher and steeper, as if the foothills of a mountain chain. Then Burl turned and peered before him.

Rising straight from the low hills, a wall of high mountains rose toward the sky, and the low-hanging clouds met their rugged flanks but half-way toward the peaks. To right and left the mountains melted into the tenuous haze, but ahead they were firm and stalwart, rising and losing their heights in the cloud-banks.

They formed a rampart which might have guarded the edge of the world, and the river flowed more and more rapidly in a deeper and narrower current toward a cleft between two rugged giants that promised to swallow the water and all that might swim in its depths or float upon its surface.

Tall, steep hills rose from either side of the swift current, their sides covered with flaking molds of an exotic shade of rose-pink, mingled here and there with lavender and purple. Rocks, not hidden beneath a coating of fungus, protruded their angular heads from the hillsides. The river valley became a gorge, and then little more than a ca�on, with beetling sides that frowned down upon the swift current running beneath them.

The small flotilla passed beneath an overhanging cliff, and then shot out to where the cliffsides drew apart and formed a deep amphitheater, whose top was hidden in the clouds.

And across this open space, on cables all of five hundred feet long, a banded spider had flung its web. It was a monster of its tribe. Its belly was swollen to a diameter of no less than two yards, and its outstretched legs would have touched eight points of a ten-yard circle.

It was hanging motionless in the center of the colossal snare as the little group of tribefolk passed underneath, and they saw the broad bands of yellow and black and silver upon its abdomen. They shivered as their little crafts were swept below.

Then they came to a little valley, where yellow sand bordered the river and there was a level space of a hundred yards on either side before the steep sides of the mountains began their rise. Here the cluster of mushroom rafts were caught in a little eddy and drawn out of the swiftly flowing current. Soon there was a soft and yielding jar. The rafts had grounded.

Led by Burl, the tribesmen waded ashore, wonderment and excitement in their hearts. Burl searched all about with his eyes. Toadstools and mushrooms, rusts and molds, even giant puff-balls grew in the little valley, but of the deadly red mushrooms he saw none.

A single bee was buzzing slowly over the tangled thickets of fungoids, and the loud voice of a cricket came in a deafening burst of sound, reechoed from the hillsides, but save for the far-flung web of the banded spider a mile or more away, there was no sign of the deadly creatures that preyed upon men.

Burl began to climb the hillside with his tribefolk after him. For an hour they toiled upward, through confused

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Have you ever thought about what fiction is? Probably, such a question may seem surprising: and so everything is clear. Every person throughout his life has to repeatedly create the works he needs for specific purposes - statements, autobiographies, dictations - using not gypsum or clay, not musical notes, not paints, but just a word. At the same time, almost every person will be very surprised if he is told that he thereby created a work of fiction, which is very different from visual art, music and sculpture making. However, everyone understands that a student's essay or dictation is fundamentally different from novels, short stories, news that are created by professional writers. In the works of professionals there is the most important difference - excogitation. But, oddly enough, in a school literature course, you don’t realize the full power of fiction. So using our website in your free time discover fiction for yourself.

Comments (0)