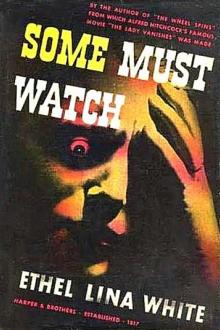

Genre Fiction. Page - 225

-glass.

"Tell Colonel Flanagan to see to it, Stephen," said the general; and thegalloper sped upon his way. The colonel, a fine old Celtic warrior, wasover at C Company in an instant.

"How are the men, Captain Foley?"

"Never better, sir," answered the senior captain, in the spirit thatmakes a Madras officer look murder if you suggest recruiting hisregiment from the Punjab.

"Stiffen them up!" cried the colonel. As he rode away a colour-sergeantseemed to trip, and fell forward into a mimosa bush. He made no effortto rise, but lay in a heap among the thorns.

"Sergeant O'Rooke's gone, sorr," cried a voice. "Never mind, lads,"said Captain Foley. "He's died like a soldier, fighting for his Queen."

"Down with the Queen!" shouted a hoarse voice from the ranks.

But the roar of the Gardner and the typewriter-like clicking of thehopper burst in at the tail of the words. Captain Foley heard them, andSubalterns Grice and Murphy heard them; but there are times when a deafear is a gift

daub on the easel.

"Ask him, then, if he would not like to learn French."

"To learn French?"

"To take lessons."

"To take lessons, my daughter? From thee?"

"From you!"

"From me, my child? How should I give lessons?"

"Pas de raisons! Ask him immediately!" said Mademoiselle Noemie, with soft brevity.

M. Nioche stood aghast, but under his daughter's eye he collected his wits, and, doing his best to assume an agreeable smile, he executed her commands. "Would it please you to receive instruction in our beautiful language?" he inquired, with an appealing quaver.

"To study French?" asked Newman, staring.

M. Nioche pressed his finger-tips together and slowly raised his shoulders. "A little conversation!"

"Conversation--that's it!" murmured Mademoiselle Noemie, who had caught the word. "The conversation of the best society."

"Our French conversation is famous, you know," M. Nioche ventured to continue. "It's a great talent."

"But

the empty ghost of a road, occasionally swigging some water from my canteen. It was rough in my bloody boots; now my ankles were chafed as well. I balanced the rucksack on my head to keep the sun off of it, but that didn't help, and the straps had already dug into my shoulders, so I took to swinging it, tossing it twenty yards in front of me, and then leisurely strolling over just to pick the sack up. No wonder I wasn't getting any nibbles from the few folks who did drive by.

It got dark fast; there was hardly any dusk at all. And behind me, I heard the roar of a convoy, but they weren't old trucks coming my way. Instead, it was wagons, sedans, curvy Studebakers, and even a few old crank cars with rumble seats and shivering fabric roofs. Town cars driving five abreast in tight formation across only two lanes of highway, eating up the shoulders, headlights suddenly blazing a terrible, beautiful amber. I cut into the wood and watched them zoom past from a little ditch I happened to fall into. Above the

s. They were careful to preserve the number of fighting men and women at 20,000, which is equal to that of the present military force. And so they passed their lives as guardians of the citizens and leaders of the Hellenes. They were a just and famous race, celebrated for their beauty and virtue all over Europe and Asia.

And now I will speak to you of their adversaries, but first I ought to explain that the Greek names were given to Solon in an Egyptian form, and he enquired their meaning and translated them. His manuscript was left with my grandfather Dropides, and is now in my possession...In the division of the earth Poseidon obtained as his portion the island of Atlantis, and there he begat children whose mother was a mortal. Towards the sea and in the centre of the island there was a very fair and fertile plain, and near the centre, about fifty stadia from the plain, there was a low mountain in which dwelt a man named Evenor and his wife Leucippe, and their daughter Cleito, of whom Poseidon became

ture upon his dome as well as the colour decorations!"

"'Tis true, my ancient?" another asked of me.

I made no repartee, continuing to sit with my chin dependent upon my cravat, but with things not the same in my heart as formerly to the arrival of that grey pongee, the grey glove, and the beautiful voice.

Since King Charles the Mad, in Paris no one has been completely free from lunacy while the spring-time is happening. There is something in the sun and the banks of the Seine. The Parisians drink sweet and fruity champagne because the good wines are already in their veins. These Parisians are born intoxicated and remain so; it is not fair play to require them to be like other human people. Their deepest feeling is for the arts; and, as everyone had declared, they are farceurs in their tragedies, tragic in their comedies. They prepare the last epigram in the tumbril; they drown themselves with enthusiasm about the alliance with Russia. In death they are witty; in war they have poetic spas

g himself into liberty and a pension at last, or hadto go out of his gas-lighted grave straight into that other dark onewhere nobody would want to intrude. My humanity was pleased to discoverhe had so much kick left in him, but I was not comforted in the least. Itoccurred to me that if Mr. Powell had the same sort of temper . . .However, I didn't give myself time to think and scuttled across the spaceat the foot of the stairs into the passage where I'd been told to try.And I tried the first door I came to, right away, without any hangingback, because coming loudly from the hall above an amazed and scandalizedvoice wanted to know what sort of game I was up to down there. "Don'tyou know there's no admittance that way?" it roared. But if there wasanything more I shut it out of my hearing by means of a door markedPrivate on the outside. It let me into a six-feet wide strip between along counter and the wall, taken off a spacious, vaulted room with agrated window and a glazed door givin

She disliked and rather despised James Houghton, saw in him elements of a hypocrite, detested his airy and gracious selfishness, his lack of human feeling, and most of all, his fairy fantasy. As James went further into life, he became a dreamer. Sad indeed that he died before the days of Freud. He enjoyed the most wonderful and fairy-like dreams, which he could describe perfectly, in charming, delicate language. At such times his beautifully modulated voice all but sang, his grey eyes gleamed fiercely under his bushy, hairy eyebrows, his pale face with its side-whiskers had a strange lueur, his long thin hands fluttered occasionally. He had become meagre in figure, his skimpy but genteel coat would be buttoned over his breast, as he recounted his dream-adventures, adventures that were half Edgar Allan Poe, half Andersen, with touches of Vathek and Lord Byron and George Macdonald: perhaps more than a touch of the last. Ladies were always struck by these accounts. But Miss Frost never felt so strongly

od tea. When shall I knock into your skull that tea's a luxury--a drink wot's only meant for swells? Perhaps you don't know what a power of money tea costs!"

"Come, now," giggled the landlady, "not to us, Mister Mipps. Not the way we gets it."

"I don't know what you means," snapped the wary sexton. "But I do wish as how you'd practise a-keepin' your mouth shut, for if you opens it much more that waggin' tongue of yours'll get us all the rope."

"Whatever is the matter?" whimpered the landlady.

"Will you do as I tell you?" shrieked the sexton.

"0h, Lord!" cried Mrs. Waggetts, dropping the precious teapot in her agitation and running out of the back door toward the school. Mipps picked up the teapot and put it on the table; then lighting his short clay pipe he waited by the window.

In the bar sat Denis Cobtree, making little progress with a Latin book that was spread open on his knee. From the other side of the counter Imogene was watching him.

She was a tall, sli

the residential quarter of a prosperous town. It should have been surrounded by an acre of well-kept garden, and situated in a private road, with lamp-posts and a pillar-box.

For all that, it offered a solidly resistant front to the solitude. Its state of excellent repair was evidence that no money was spared to keep it weather-proof. There was no blistered paint, no defective guttering. The whole was somehow suggestive of a house which, at a pinch, could be rendered secure as an armored car.

It glowed with electric-light, for Oates' principal duty was to work the generating plant. A single wire overhead was also a comfortable reassurance of its link with civilization.

Helen no longer felt any wish to linger outside. The evening mists were rising so that the evergreen shrubs, which clumped the lawn, appeared to quiver into life. Viewed through a veil of vapor, they looked black and grim, like mourners assisting at a funeral.

"If I don't hurry, they'll get between me and the house,

down into the stress and worry of life, when I found you so highabove it? And what can I offer you in exchange?' These are thethoughts which come back and back all day, and leave me in theblackest fit of despondency. I confessed to you that I had darkhumours, but never one so hopeless as this. I do not wish my worstenemy to be as unhappy as I have been to-day.

Write to me, my own darling Maude, and tell me all you think, yourvery inmost soul, in this matter. Am I right? Have I asked too muchof you? Does the change frighten you? You will have this in themorning, and I should have my answer by the evening post. I shallmeet the postman. How hard I shall try not to snatch the letter fromhim, or to give myself away. Wilson has been in worrying me withfoolish talk, while my thoughts were all of our affairs. He workedme up into a perfectly homicidal frame of mind, but I hope that Ikept on smiling and was not discourteous to him. I wonder which isright, to be polite but hypocritical, or