Genre Fiction. Page - 259

d the three were immediately admitted.

Gowing called to me across the gate, and said: "We shan't be a minute." I waited for them the best part of an hour. When they appeared they were all in most excellent spirits, and the only one who made an effort to apologise was Mr. Stillbrook, who said to me: "It was very rough on you to be kept waiting, but we had another spin for S. and B.'s." I walked home in silence; I couldn't speak to them. I felt very dull all the evening, but deemed it advisable NOT to say anything to Carrie about the matter.

April 16.--After business, set to work in the garden. When it got dark I wrote to Cummings and Gowing (who neither called, for a wonder; perhaps they were ashamed of themselves) about yesterday's adventure at "The Cow and Hedge." Afterwards made up my mind not to write YET.

April 17.--Thought I would write a kind little note to Gowing and Cummings about last Sunday, and warning them against Mr. Stillbrook. Afterwards, thinking the matter over, tore up t

to play their very best to win against us. He also admitted that there was open betting going on, with heavy odds on Harmony."

Jack sighed.

"That all agrees with what came to me in a side way," he explained. "In other words, the way things stand, there will be a big lot of money change hands in case Harmony does win. And those sporting men who came up from the city wouldn't think it out of the way to pay a good fat bribe if they could make sure that some player on the Chester team would throw the game, in case it began to look bad for Harmony!"

Toby almost fell off his seat on hearing Jack say that.

"My stars! and do you suspect Fred of entering into such a base conspiracy as that would be, Jack?" he demanded, hoarsely; while Steve held his very breath as he waited for the other to reply.

"Remember, not one word of this to a living soul," cautioned Jack; "give me your solemn promise, both of you, before I say anything more."

Both boys held up a right hand pro

He found his companions dining, and joining them, he made a good meal, and at its conclusion all hands repaired to the bar again, and indulged in several more drinks.

Jesse then startled his companions by pulling out his big wad of bills, and paying the landlord for their fare.

The moment the gang got him alone, Frank whispered:

"Where did you get the roll, Jess?"

"From Jack Wright," laughed the outlaw.

"Tell us about it!"

"Certainly. It was the easiest game I ever played, and I got $5,000 out of it, too. Ha, ha, ha!"

Looks of intense astonishment appeared on the faces of his friends.

He then explained what he had done.

A roar of delight went up from the gang when he finished.

"Bully for you, Jess!"

"Oh, Lord, what a game!"

"You've done splendidly."

"What a roasting for the bank!"

was turned to other objects; namely, to wonderful slave women who were waiting for the bathers. Two of them, Africans, resembling noble statues of ebony, began to anoint their bodies with delicate perfumes from Arabia; others, Phrygians, skilled in hairdressing, held in their hands, which were bending and flexible as serpents, combs and mirrors of polished steel; two Grecian maidens from Kos, who were simply like deities, waited as vestiplicæ, till the moment should come to put statuesque folds in the togas of the lords.

"By the cloud-scattering Zeus!" said Marcus Vinicius, "what a choice thou hast!"

"I prefer choice to numbers," answered Petronius. "My whole 'familia' [household servants] in Rome does not exceed four hundred, and I judge that for personal attendance only upstarts need a greater number of people."

"More beautiful bodies even Bronzebeard does not possess," said Vinicius, distending his nostrils.

"Thou art my relative," answered Petronius, with a certain friend

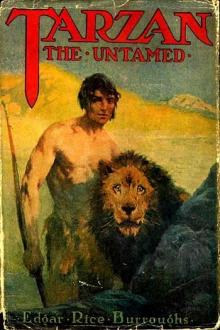

ization meant to Tarzan of the Apes a curtailment of freedom in all its aspects--freedom of action, freedom of thought, freedom of love, freedom of hate. Clothes he abhorred--uncomfortable, hideous, confining things that reminded him somehow of bonds securing him to the life he had seen the poor creatures of London and Paris living. Clothes were the emblems of that hypocrisy for which civilization stood--a pretense that the wearers were ashamed of what the clothes covered, of the human form made in the semblance of God. Tarzan knew how silly and pathetic the lower orders of animals appeared in the clothing of civilization, for he had seen several poor creatures thus appareled in various traveling shows in Europe, and he knew, too, how silly and pathetic man appears in them since the only men he had seen in the first twenty years of his life had been, like himself, naked savages. The ape-man had a keen admiration for a well-muscled, well-proportioned body, whether lion, or antelope, or man, and it had ever bee

d is a mother apiece.

I plunged into this thing lightly enough, partly because you were too persuasive, and mostly, I honestly think, because that scurrilous Gordon Hallock laughed so uproariously at the idea of my being able to manage an asylum. Between you all you hypnotized me. And then of course, after I began reading up on the subject and visiting all those seventeen institutions, I got excited over orphans, and wanted to put my own ideas into practice. But now I'm aghast at finding myself here; it's such a stupendous undertaking. The future health and happiness of a hundred human beings lie in my hands, to say nothing of their three or four hundred children and thousand grandchildren. The thing's geometrically progressive. It's awful. Who am I to undertake this job? Look, oh, look for another superintendent!

Jane says dinner's ready. Having eaten two of your institution meals, the thought of another doesn't excite me.

LATER.

The staff had mutton hash and spinach, with tapioca

ormed." say, "to perform."

"He drinks wine at dinner," means that such is his habit; "he is drinking wine at dinner," refers to one particular time and occasion.

Adverbs are often inelegantly used instead of adjectives; as, "the then ministry," for "the ministry of that time."

Of the phrases "never so good," or, "ever so good," as to whether one is preferable to the other, authority is divided. Modern usage inclines to the latter, while ancient preferred the former, as in the Scriptural expression, "charm he never so wisely."

Yea and nay are not equivalent to yes and no; the latter are directly affirmative and negative, while the former are variously employed.

Of prepositions, it has been frequently said, that no words in the language are so liable to be incorrectly used. For example, "The love of God," may mean either "His love to us," or, "our love to Him."

rike Europe. Piff! My cig's out. I can'tsmoke the truck the steward sells. Any gen'elman got a realTurkish cig on him?"

The chief engineer entered for a moment, red, smiling, and wet."Say, Mac," cried Harvey cheerfully, "how are we hitting it?"

"Vara much in the ordinary way," was the grave reply. "The youngare as polite as ever to their elders, an' their elders are e'entryin' to appreciate it."

A low chuckle came from a corner. The German opened hiscigar-case and handed a skinny black cigar to Harvey.

"Dot is der broper apparatus to smoke, my young friendt," he said."You vill dry it? Yes? Den you vill be efer so happy."

Harvey lit the unlovely thing with a flourish: he felt that he wasgetting on in grownup society.

"It would take more 'n this to keel me over," he said, ignorant thathe was lighting that terrible article, a Wheeling 'stogie'.

"Dot we shall bresently see," said the German. "Where are wenow, Mr. Mactonal'?"

"Just there or thereabouts, Mr. Schaefer," said the eng

napping sound from below, and David's foot was released. He unstuck the snag from his shirt, pushed his way out of the thicket, and sat down weakly on the grass. Whew! At least the bird was not going to harm him. It seemed to be quite a kindly creature, really. He had just frightened it and made it angry by bursting out of the bushes so suddenly.

He heard a flailing in the thicket, followed by the bird's anxious voice: "Hello! Are you still there?"

"Yes. What--?"

There were more sounds of struggle. "This is rather awkward. I--the fact is, I am afraid, that I am stuck myself. Could you--"

"Yes, of course," said David. He smiled to himself, a little shakily, and re-entered the thicket. When he had disentangled the bird, the two of them sat down on the grass and looked at each other. They hesitated, not quite sure how to begin.

"I trust," said the bird at last, "that you are not of a scientific turn of mind?"

"I don't know," said David. "I'm interested in things, if that

m in the office."

"God grant it!" the clerk said fervently.

For the moment, Sir Giles was staggered. "Have you heard something that you haven't told me yet?" he asked.

"No, sir. I am only bearing in mind something which--with all respect--I think you have forgotten. The last tenant on that bit of land in Kerry refused to pay his rent. Mr. Arthur has taken what they call an evicted farm. It's my firm belief," said the head clerk, rising and speaking earnestly, "that the person who has addressed those letters to you knows Mr. Arthur, and knows he is in danger--and is trying to save your nephew (by means of your influence), at the risk of his own life."

Sir Giles shook his head. "I call that a far-fetched interpretation, Dennis. If what you say is true, why didn't the writer of those anonymous letters address himself to Arthur, instead of to me?"

"I gave it as my opinion just now, sir, that the writer of the letter knew Mr. Arthur."

"So you did. And what of that?"