Genre Fiction. Page - 283

e were in some way to blame. Behind her, with the same offended look, stood a wealthy young man, and examining magistrate, whom Peter Ivanovich also knew and who was her fiance, as he had heard. He bowed mournfully to them and was about to pass into the death-chamber, when from under the stairs appeared the figure of Ivan Ilych's schoolboy son, who was extremely like his father. He seemed a little Ivan Ilych, such as Peter Ivanovich remembered when they studied law together. His tear-stained eyes had in them the look that is seen in the eyes of boys of thirteen or fourteen who are not pure-minded. When he saw Peter Ivanovich he scowled morosely and shamefacedly. Peter Ivanovich nodded to him and entered the death-chamber. The service began: candles, groans, incense, tears, and sobs. Peter Ivanovich stood looking gloomily down at his feet. He did not look once at the dead man, did not yield to any depressing influence, and was one of the first to leave the room. There was no one in the anteroom, but Gerasim da

lins, and haunted fields, and haunted brooks, and haunted bridges, and haunted houses, and particularly of the headless horseman, or Galloping Hessian of the Hollow, as they sometimes called him. He would delight them equally by his anecdotes of witchcraft, and of the direful omens and portentous sights and sounds in the air, which prevailed in the earlier times of Connecticut; and would frighten them woefully with speculations upon comets and shooting stars; and with the alarming fact that the world did absolutely turn round, and that they were half the time topsy-turvy!

But if there was a pleasure in all this, while snugly cuddling in the chimney corner of a chamber that was all of a ruddy glow from the crackling wood fire, and where, of course, no spectre dared to show its face, it was dearly purchased by the terrors of his subsequent walk homewards. What fearful shapes and shadows beset his path, amidst the dim and ghastly glare of a snowy night! With what wistful look did he eye every trembling ra

"Look sharp, Marco! The quadruple knot!"

Before he had even time to stand on the defensive, Rudolf Kesselbach was tied up in a network of cords that cut into his flesh at the least attempt which he made to struggle. His arms were fixed behind his back, his body fastened to the chair and his legs tied together like the legs of a mummy.

"Search him, Marco."

Marco searched him. Two minutes after, he handed his chief a little flat, nickel-plated key, bearing the numbers 16 and 9.

"Capital. No morocco pocket-case?"

"No, governor."

"It is in the safe. Mr. Kesselbach, will you tell me the secret cypher that opens the lock?"

"No."

"You refuse?"

"Yes."

"Marco!"

"Yes, governor."

"Place the barrel of your revolver against the gentleman's temple."

"It's there."

"Now put your finger to the trigger."

"Ready."

"Well, Kesselbach, old chap, do you intend to speak?"

"No."

"I'll give you ten secon

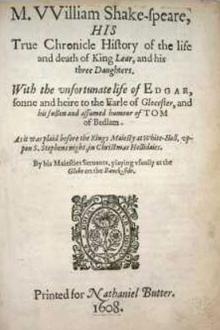

her worth. In my true heart

I find she names my very deed of love;

Only she comes too short,--that I profess

Myself an enemy to all other joys

Which the most precious square of sense possesses,

And find I am alone felicitate

In your dear highness' love.

Cor.

[Aside.] Then poor Cordelia!

And yet not so; since, I am sure, my love's

More richer than my tongue.

Lear.

To thee and thine hereditary ever

Remain this ample third of our fair kingdom;

No less in space, validity, and pleasure

Than that conferr'd on Goneril.--Now, our joy,

Although the last, not least; to whose young love

The vines of France and milk of Burgundy

Strive to be interess'd; what can you say to draw

A third more opulent than your sisters? Speak.

Cor.

Nothing, my lord.

Lear.

Nothing!

Cor.

Nothing.

Lear.

Nothing can come of nothing: speak again.

Cor.

Unhappy that I am, I cannot heave

My heart into my mouth

thin a tiny oasis. Close by was an Arab douar of some eight or ten tents.

I had come down from the north to hunt lion. My party consisted of a dozen children of the desert--I was the only "white" man. As we approached the little clump of verdure I saw the man come from his tent and with hand-shaded eyes peer intently at us. At sight of me he advanced rapidly to meet us.

"A white man!" he cried. "May the good Lord be praised! I have been watching you for hours, hoping against hope that THIS time there would be a white man. Tell me the date. What year is it?"

And when I had told him he staggered as though he had been struck full in the face, so that he was compelled to grasp my stirrup leather for support.

"It cannot be!" he cried after a moment. "It cannot be! Tell me that you are mistaken, or that you are but joking."

"I am telling you the truth, my friend," I replied. "Why should I deceive a stranger, or attempt to, in so simple a matter as the date?"

For some time h

Professor Carbonic was diligently at work in his spacious laboratory, analyzing, mixing and experimenting. He had been employed for more than fifteen years in the same pursuit of happiness, in the same house, same laboratory, and attended by the same servant woman, who in her long period of service had attained the plumpness and respectability of two hundred and ninety pounds.

[Illustration: The electric current lighted up everything in sight!]

"Mag Nesia," called the professor. The servant's name was Maggie Nesia--Professor Carbonic had contracted the title to save time, for in fifteen years he had not mounted the heights of greatness; he must work harder and faster as life is short, and eliminate such shameful waste of time as putting the "gie" on Maggie.

"Mag Nesia!" the professor repeated.

The old woman rolled slowly into the room.

"Get

y the sea.

CATHLEENHow would they be Michael's, Nora. How would he go the lengthof that way to the far north?

NORAThe young priest says he's known the like of it. "If it'sMichael's they are," says he, "you can tell herself he's got aclean burial by the grace of God, and if they're not his, letno one say a word about them, for she'll be getting her death,"says he, "with crying and lamenting."

[The door which Nora half closed is blown open by a gust ofwind.]

CATHLEEN[Looking out anxiously.]

Did you ask him would he stop Bartley going this day with thehorses to the Galway fair?

NORA"I won't stop him," says he, "but let you not be afraid.Herself does be saying prayers half through the night, and theAlmighty God won't leave her destitute," says he, "with no sonliving."

CATHLEENIs the sea bad by the white rocks, Nora?

NORAMiddling bad, God help us. There's a great roaring in thewest, and it's worse it'll be getting when the tide's turned tothe wind.

[She goes over to

am not to blame, mother, believe that. Only (it is not a pleasant thing to tell) Mrs. Englehart has taken it into that supremely foolish head of hers to be jealous of me--of poor, plain Joan Kennedy! The major, a kind old soul, has spoken a friendly word or two in passing and--behold the result! Don't let us talk about it. I'll start out to-morrow morning and search all Quebec, and get a situation or perish in the attempt. And now, Mistress Jessie, I'll take a cup of tea."

I threw off my shawl and bonnet, laughing for fear I should break down and cry, and took my seat. As I did so, there came a loud knock at the door. So loud, that Jessie nearly dropped the snub-nosed teapot.

"Good gracious, Joan! who is this?"

I walked to the door and opened it--then fell back aghast. For firelight and candlelight streamed full across the face of the lady I had seen at the House to Let.

"May I come in?"

She did not wait for permission. She walked in past me, straight to the fire, a

ulled up at the kerb.

The driver leant over the shining apron which partially protected him from the weather, and shouted:

"Is Miss Beale there?"

The girl started in surprise, taking a step toward the cab.

"I am Miss Beale," she said.

"Your editor has sent me for you," said the man briskly.

The editor of the Megaphone had been guilty of many eccentric acts. He had expressed views on her drawing which she shivered to recall. He had aroused her in the middle of the night to sketch dresses at a fancy dress ball, but never before had he done anything so human as to send a taxi for her. Nevertheless, she would not look at the gift cab too closely, and she stepped into the warm interior.

The windows were veiled with the snow and the sleet which had been falling all the time she had been in the theatre. She saw blurred lights flash past, and realised that the taxi was going at a good pace. She rubbed the windows and tried to look out after a while. Then she e

of the slaves, or to march to Mexico--see if I would go"; and yet these very men have each, directly by their allegiance, and so indirectly, at least, by their money, furnished a substitute. The soldier is applauded who refuses to serve in an unjust war by those who do not refuse to sustain the unjust government which makes the war; is applauded by those whose own act and authority he disregards and sets at naught; as if the state were penitent to that degree that it hired one to scourge it while it sinned, but not to that degree that it left off sinning for a moment. Thus, under the name of Order and Civil Government, we are all made at last to pay homage to and support our own meanness. After the first blush of sin comes its indifference; and from immoral it becomes, as it were, unmoral, and not quite unnecessary to that life which we have made.

The broadest and most prevalent error requires the most disinterested virtue to sustain it. The slight reproach to which the virtue of patriotism is commonly