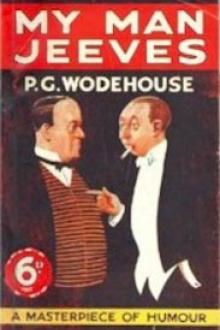

My Man Jeeves by P. G. Wodehouse (best biographies to read .txt) 📖

- Author: P. G. Wodehouse

Book online «My Man Jeeves by P. G. Wodehouse (best biographies to read .txt) 📖». Author P. G. Wodehouse

Jeeves was happy, partly because he loves to exercise his giant brain, and partly because he was having a corking time among the bright lights. I saw him one night at the Midnight Revels. He was sitting at a table on the edge of the dancing floor, doing himself remarkably well with a fat cigar and a bottle of the best. I’d never imagined he could look so nearly human. His face wore an expression of austere benevolence, and he was making notes in a small book.

As for the rest of us, I was feeling pretty good, because I was fond of old Rocky and glad to be able to do him a good turn. Rocky was perfectly contented, because he was still able to sit on fences in his pyjamas and watch worms. And, as for the aunt, she seemed tickled to death. She was getting Broadway at pretty long range, but it seemed to be hitting her just right. I read one of her letters to Rocky, and it was full of life.

But then Rocky’s letters, based on Jeeves’s notes, were enough to buck anybody up. It was rummy when you came to think of it. There was I, loving the life, while the mere mention of it gave Rocky a tired feeling; yet here is a letter I wrote to a pal of mine in London:

“DEAR FREDDIE,—Well, here I am in New York. It’s not a bad place. I’m not having a bad time. Everything’s pretty all right. The cabarets aren’t bad. Don’t know when I shall be back. How’s everybody? Cheer-o!—Yours,

“BERTIE.

“PS.—Seen old Ted lately?”

Not that I cared about Ted; but if I hadn’t dragged him in I couldn’t have got the confounded thing on to the second page.

Now here’s old Rocky on exactly the same subject:

“DEAREST AUNT ISABEL,—How can I ever thank you enough for giving me the opportunity to live in this astounding city! New York seems more wonderful every day.

“Fifth Avenue is at its best, of course, just now. The dresses are magnificent!”

Wads of stuff about the dresses. I didn’t know Jeeves was such an authority.

“I was out with some of the crowd at the Midnight Revels the other night. We took in a show first, after a little dinner at a new place on Forty-third Street. We were quite a gay party. Georgie Cohan looked in about midnight and got off a good one about Willie Collier. Fred Stone could only stay a minute, but Doug. Fairbanks did all sorts of stunts and made us roar. Diamond Jim Brady was there, as usual, and Laurette Taylor showed up with a party. The show at the Revels is quite good. I am enclosing a programme.

“Last night a few of us went round to Frolics on the Roof——”

And so on and so forth, yards of it. I suppose it’s the artistic temperament or something. What I mean is, it’s easier for a chappie who’s used to writing poems and that sort of tosh to put a bit of a punch into a letter than it is for a chappie like me. Anyway, there’s no doubt that Rocky’s correspondence was hot stuff. I called Jeeves in and congratulated him.

“Jeeves, you’re a wonder!”

“Thank you, sir.”

“How you notice everything at these places beats me. I couldn’t tell you a thing about them, except that I’ve had a good time.”

“It’s just a knack, sir.”

“Well, Mr. Todd’s letters ought to brace Miss Rockmetteller all right, what?”

“Undoubtedly, sir,” agreed Jeeves.

And, by Jove, they did! They certainly did, by George! What I mean to say is, I was sitting in the apartment one afternoon, about a month after the thing had started, smoking a cigarette and resting the old bean, when the door opened and the voice of Jeeves burst the silence like a bomb.

It wasn’t that he spoke loudly. He has one of those soft, soothing voices that slide through the atmosphere like the note of a far-off sheep. It was what he said made me leap like a young gazelle.

“Miss Rockmetteller!”

And in came a large, solid female.

The situation floored me. I’m not denying it. Hamlet must have felt much as I did when his father’s ghost bobbed up in the fairway. I’d come to look on Rocky’s aunt as such a permanency at her own home that it didn’t seem possible that she could really be here in New York. I stared at her. Then I looked at Jeeves. He was standing there in an attitude of dignified detachment, the chump, when, if ever he should have been rallying round the young master, it was now.

Rocky’s aunt looked less like an invalid than any one I’ve ever seen, except my Aunt Agatha. She had a good deal of Aunt Agatha about her, as a matter of fact. She looked as if she might be deucedly dangerous if put upon; and something seemed to tell me that she would certainly regard herself as put upon if she ever found out the game which poor old Rocky had been pulling on her.

“Good afternoon,” I managed to say.

“How do you do?” she said. “Mr. Cohan?”

“Er—no.”

“Mr. Fred Stone?”

“Not absolutely. As a matter of fact, my name’s Wooster—Bertie Wooster.”

She seemed disappointed. The fine old name of Wooster appeared to mean nothing in her life.

“Isn’t Rockmetteller home?” she said. “Where is he?”

She had me with the first shot. I couldn’t think of anything to say. I couldn’t tell her that Rocky was down in the country, watching worms.

There was the faintest flutter of sound in the background. It was the respectful cough with which Jeeves announces that he is about to speak without having been spoken to.

“If you remember, sir, Mr. Todd went out in the automobile with a party in the afternoon.”

“So he did, Jeeves; so he did,” I said, looking at my watch. “Did he say when he would be back?”

“He gave me to understand, sir, that he would be somewhat late in returning.”

He vanished; and the aunt took the chair which I’d forgotten to offer her. She looked at me in rather a rummy way. It was a nasty look. It made me feel as if I were something the dog had brought in and intended to bury later on, when he had time. My own Aunt Agatha, back in England, has looked at me in exactly the same way many a time, and it never fails to make my spine curl.

“You seem very much at home here, young man. Are you a great friend of Rockmetteller’s?”

“Oh, yes, rather!”

She frowned as if she had expected better things of old Rocky.

“Well, you need to be,” she said, “the way you treat his flat as your own!”

I give you my word, this quite unforeseen slam simply robbed me of the power of speech. I’d been looking on myself in the light of the dashing host, and suddenly to be treated as an intruder jarred me. It wasn’t, mark you, as if she had spoken in a way to suggest that she considered my presence in the place as an ordinary social call. She obviously looked on me as a cross between a burglar and the plumber’s man come to fix the leak in the bathroom. It hurt her—my being there.

At this juncture, with the conversation showing every sign of being about to die in awful agonies, an idea came to me. Tea—the good old stand-by.

“Would you care for a cup of tea?” I said.

“Tea?”

She spoke as if she had never heard of the stuff.

“Nothing like a cup after a journey,” I said. “Bucks you up! Puts a bit of zip into you. What I mean is, restores you, and so on, don’t you know. I’ll go and tell Jeeves.”

I tottered down the passage to Jeeves’s lair. The man was reading the evening paper as if he hadn’t a care in the world.

“Jeeves,” I said, “we want some tea.”

“Very good, sir.”

“I say, Jeeves, this is a bit thick, what?”

I wanted sympathy, don’t you know—sympathy and kindness. The old nerve centres had had the deuce of a shock.

“She’s got the idea this place belongs to Mr. Todd. What on earth put that into her head?”

Jeeves filled the kettle with a restrained dignity.

“No doubt because of Mr. Todd’s letters, sir,” he said. “It was my suggestion, sir, if you remember, that they should be addressed from this apartment in order that Mr. Todd should appear to possess a good central residence in the city.”

I remembered. We had thought it a brainy scheme at the time.

“Well, it’s bally awkward, you know, Jeeves. She looks on me as an intruder. By Jove! I suppose she thinks I’m someone who hangs about here, touching Mr. Todd for free meals and borrowing his shirts.”

“Yes, sir.”

“It’s pretty rotten, you know.”

“Most disturbing, sir.”

“And there’s another thing: What are we to do about Mr. Todd? We’ve got to get him up here as soon as ever we can. When you have brought the tea you had better go out and send him a telegram, telling him to come up by the next train.”

“I have already done so, sir. I took the liberty of writing the message and dispatching it by the lift attendant.”

“By Jove, you think of everything, Jeeves!”

“Thank you, sir. A little buttered toast with the tea? Just so, sir. Thank you.”

I went back to the sitting-room. She hadn’t moved an inch. She was still bolt upright on the edge of her chair, gripping her umbrella like a hammer-thrower. She gave me another of those looks as I came in. There was no doubt about it; for some reason she had taken a dislike to me. I suppose because I wasn’t George M. Cohan. It was a bit hard on a chap.

“This is a surprise, what?” I said, after about five minutes’ restful silence, trying to crank the conversation up again.

“What is a surprise?”

“Your coming here, don’t you know, and so on.”

She raised her eyebrows and drank me in a bit more through her glasses.

“Why is it surprising that I should visit my only nephew?” she said.

Put like that, of course, it did seem reasonable.

“Oh, rather,” I said. “Of course! Certainly. What I mean is——”

Jeeves projected himself into the room with the tea. I was jolly glad to see him. There’s nothing like having a bit of business arranged for one when one isn’t certain of one’s lines. With the teapot to fool about with I felt happier.

“Tea, tea, tea—what? What?” I said.

It wasn’t what I had meant to say. My idea had been to be a good deal more formal, and so on. Still, it covered the situation. I poured her out a cup. She sipped it and put the cup down with a shudder.

“Do you mean to say, young man,” she said frostily, “that you expect me to drink this stuff?”

“Rather! Bucks you up, you know.”

“What do you mean by the expression ‘Bucks you up’?”

“Well, makes you full of beans, you know. Makes you fizz.”

“I don’t understand a word you say. You’re English, aren’t you?”

I admitted it. She didn’t say a word. And somehow she did it in a way that made it worse than if she had spoken for hours. Somehow it was brought home to me that she didn’t like Englishmen, and that if she had had to meet an Englishman, I was the one she’d have chosen last.

Conversation languished again after that.

Then I tried again. I was becoming more convinced every moment that you can’t make a real lively salon with a couple of people, especially if one of them lets it go a word at a time.

“Are you comfortable at your hotel?” I said.

“At which hotel?”

“The hotel you’re staying at.”

“I am not staying at an hotel.”

“Stopping with friends—what?”

“I am naturally stopping with my nephew.”

I didn’t get it for the moment; then it hit me.

“What! Here?” I gurgled.

“Certainly! Where else should I go?”

The full horror of the situation rolled over me like a wave. I couldn’t see what on earth I was to do. I couldn’t explain that this wasn’t Rocky’s flat without giving the poor old chap away hopelessly, because she would then ask me where he did live, and then he would be right in the soup. I was trying to induce the old bean to recover from the shock and produce some results when she spoke again.

“Will you kindly tell my nephew’s man-servant to prepare my room? I wish to lie down.”

“Your nephew’s man-servant?”

“The man you call Jeeves. If Rockmetteller has gone for an automobile ride, there is no need for you to wait for him. He will naturally wish to be alone

Comments (0)