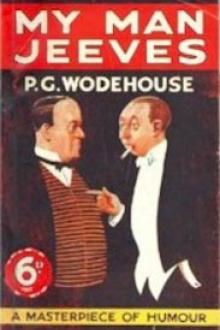

My Man Jeeves by P. G. Wodehouse (best biographies to read .txt) 📖

- Author: P. G. Wodehouse

Book online «My Man Jeeves by P. G. Wodehouse (best biographies to read .txt) 📖». Author P. G. Wodehouse

The next night I came home early, after a lonely dinner at a place which I’d chosen because there didn’t seem any chance of meeting Motty there. The sitting-room was quite dark, and I was just moving to switch on the light, when there was a sort of explosion and something collared hold of my trouser-leg. Living with Motty had reduced me to such an extent that I was simply unable to cope with this thing. I jumped backward with a loud yell of anguish, and tumbled out into the hall just as Jeeves came out of his den to see what the matter was.

“Did you call, sir?”

“Jeeves! There’s something in there that grabs you by the leg!”

“That would be Rollo, sir.”

“Eh?”

“I would have warned you of his presence, but I did not hear you come in. His temper is a little uncertain at present, as he has not yet settled down.”

“Who the deuce is Rollo?”

“His lordship’s bull-terrier, sir. His lordship won him in a raffle, and tied him to the leg of the table. If you will allow me, sir, I will go in and switch on the light.”

There really is nobody like Jeeves. He walked straight into the sitting-room, the biggest feat since Daniel and the lions’ den, without a quiver. What’s more, his magnetism or whatever they call it was such that the dashed animal, instead of pinning him by the leg, calmed down as if he had had a bromide, and rolled over on his back with all his paws in the air. If Jeeves had been his rich uncle he couldn’t have been more chummy. Yet directly he caught sight of me again, he got all worked up and seemed to have only one idea in life—to start chewing me where he had left off.

“Rollo is not used to you yet, sir,” said Jeeves, regarding the bally quadruped in an admiring sort of way. “He is an excellent watchdog.”

“I don’t want a watchdog to keep me out of my rooms.”

“No, sir.”

“Well, what am I to do?”

“No doubt in time the animal will learn to discriminate, sir. He will learn to distinguish your peculiar scent.”

“What do you mean—my peculiar scent? Correct the impression that I intend to hang about in the hall while life slips by, in the hope that one of these days that dashed animal will decide that I smell all right.” I thought for a bit. “Jeeves!”

“Sir?”

“I’m going away—to-morrow morning by the first train. I shall go and stop with Mr. Todd in the country.”

“Do you wish me to accompany you, sir?”

“No.”

“Very good, sir.”

“I don’t know when I shall be back. Forward my letters.”

“Yes, sir.”

As a matter of fact, I was back within the week. Rocky Todd, the pal I went to stay with, is a rummy sort of a chap who lives all alone in the wilds of Long Island, and likes it; but a little of that sort of thing goes a long way with me. Dear old Rocky is one of the best, but after a few days in his cottage in the woods, miles away from anywhere, New York, even with Motty on the premises, began to look pretty good to me. The days down on Long Island have forty-eight hours in them; you can’t get to sleep at night because of the bellowing of the crickets; and you have to walk two miles for a drink and six for an evening paper. I thanked Rocky for his kind hospitality, and caught the only train they have down in those parts. It landed me in New York about dinner-time. I went straight to the old flat. Jeeves came out of his lair. I looked round cautiously for Rollo.

“Where’s that dog, Jeeves? Have you got him tied up?”

“The animal is no longer here, sir. His lordship gave him to the porter, who sold him. His lordship took a prejudice against the animal on account of being bitten by him in the calf of the leg.”

I don’t think I’ve ever been so bucked by a bit of news. I felt I had misjudged Rollo. Evidently, when you got to know him better, he had a lot of intelligence in him.

“Ripping!” I said. “Is Lord Pershore in, Jeeves?”

“No, sir.”

“Do you expect him back to dinner?”

“No, sir.”

“Where is he?”

“In prison, sir.”

Have you ever trodden on a rake and had the handle jump up and hit you? That’s how I felt then.

“In prison!”

“Yes, sir.”

“You don’t mean—in prison?”

“Yes, sir.”

I lowered myself into a chair.

“Why?” I said.

“He assaulted a constable, sir.”

“Lord Pershore assaulted a constable!”

“Yes, sir.”

I digested this.

“But, Jeeves, I say! This is frightful!”

“Sir?”

“What will Lady Malvern say when she finds out?”

“I do not fancy that her ladyship will find out, sir.”

“But she’ll come back and want to know where he is.”

“I rather fancy, sir, that his lordship’s bit of time will have run out by then.”

“But supposing it hasn’t?”

“In that event, sir, it may be judicious to prevaricate a little.”

“How?”

“If I might make the suggestion, sir, I should inform her ladyship that his lordship has left for a short visit to Boston.”

“Why Boston?”

“Very interesting and respectable centre, sir.”

“Jeeves, I believe you’ve hit it.”

“I fancy so, sir.”

“Why, this is really the best thing that could have happened. If this hadn’t turned up to prevent him, young Motty would have been in a sanatorium by the time Lady Malvern got back.”

“Exactly, sir.”

The more I looked at it in that way, the sounder this prison wheeze seemed to me. There was no doubt in the world that prison was just what the doctor ordered for Motty. It was the only thing that could have pulled him up. I was sorry for the poor blighter, but, after all, I reflected, a chappie who had lived all his life with Lady Malvern, in a small village in the interior of Shropshire, wouldn’t have much to kick at in a prison. Altogether, I began to feel absolutely braced again. Life became like what the poet Johnnie says—one grand, sweet song. Things went on so comfortably and peacefully for a couple of weeks that I give you my word that I’d almost forgotten such a person as Motty existed. The only flaw in the scheme of things was that Jeeves was still pained and distant. It wasn’t anything he said or did, mind you, but there was a rummy something about him all the time. Once when I was tying the pink tie I caught sight of him in the looking-glass. There was a kind of grieved look in his eye.

And then Lady Malvern came back, a good bit ahead of schedule. I hadn’t been expecting her for days. I’d forgotten how time had been slipping along. She turned up one morning while I was still in bed sipping tea and thinking of this and that. Jeeves flowed in with the announcement that he had just loosed her into the sitting-room. I draped a few garments round me and went in.

There she was, sitting in the same arm-chair, looking as massive as ever. The only difference was that she didn’t uncover the teeth, as she had done the first time.

“Good morning,” I said. “So you’ve got back, what?”

“I have got back.”

There was something sort of bleak about her tone, rather as if she had swallowed an east wind. This I took to be due to the fact that she probably hadn’t breakfasted. It’s only after a bit of breakfast that I’m able to regard the world with that sunny cheeriness which makes a fellow the universal favourite. I’m never much of a lad till I’ve engulfed an egg or two and a beaker of coffee.

“I suppose you haven’t breakfasted?”

“I have not yet breakfasted.”

“Won’t you have an egg or something? Or a sausage or something? Or something?”

“No, thank you.”

She spoke as if she belonged to an anti-sausage society or a league for the suppression of eggs. There was a bit of a silence.

“I called on you last night,” she said, “but you were out.”

“Awfully sorry! Had a pleasant trip?”

“Extremely, thank you.”

“See everything? Niag’ra Falls, Yellowstone Park, and the jolly old Grand Canyon, and what-not?”

“I saw a great deal.”

There was another slightly frappé silence. Jeeves floated silently into the dining-room and began to lay the breakfast-table.

“I hope Wilmot was not in your way, Mr. Wooster?”

I had been wondering when she was going to mention Motty.

“Rather not! Great pals! Hit it off splendidly.”

“You were his constant companion, then?”

“Absolutely! We were always together. Saw all the sights, don’t you know. We’d take in the Museum of Art in the morning, and have a bit of lunch at some good vegetarian place, and then toddle along to a sacred concert in the afternoon, and home to an early dinner. We usually played dominoes after dinner. And then the early bed and the refreshing sleep. We had a great time. I was awfully sorry when he went away to Boston.”

“Oh! Wilmot is in Boston?”

“Yes. I ought to have let you know, but of course we didn’t know where you were. You were dodging all over the place like a snipe—I mean, don’t you know, dodging all over the place, and we couldn’t get at you. Yes, Motty went off to Boston.”

“You’re sure he went to Boston?”

“Oh, absolutely.” I called out to Jeeves, who was now messing about in the next room with forks and so forth: “Jeeves, Lord Pershore didn’t change his mind about going to Boston, did he?”

“No, sir.”

“I thought I was right. Yes, Motty went to Boston.”

“Then how do you account, Mr. Wooster, for the fact that when I went yesterday afternoon to Blackwell’s Island prison, to secure material for my book, I saw poor, dear Wilmot there, dressed in a striped suit, seated beside a pile of stones with a hammer in his hands?”

I tried to think of something to say, but nothing came. A chappie has to be a lot broader about the forehead than I am to handle a jolt like this. I strained the old bean till it creaked, but between the collar and the hair parting nothing stirred. I was dumb. Which was lucky, because I wouldn’t have had a chance to get any persiflage out of my system. Lady Malvern collared the conversation. She had been bottling it up, and now it came out with a rush:

“So this is how you have looked after my poor, dear boy, Mr. Wooster! So this is how you have abused my trust! I left him in your charge, thinking that I could rely on you to shield him from evil. He came to you innocent, unversed in the ways of the world, confiding, unused to the temptations of a large city, and you led him astray!”

I hadn’t any remarks to make. All I could think of was the picture of Aunt Agatha drinking all this in and reaching out to sharpen the hatchet against my return.

“You deliberately——”

Far away in the misty distance a soft voice spoke:

“If I might explain, your ladyship.”

Jeeves had projected himself in from the dining-room and materialized on the rug. Lady Malvern tried to freeze him with a look, but you can’t do that sort of thing to Jeeves. He is look-proof.

“I fancy, your ladyship, that you have misunderstood Mr. Wooster, and that he may have given you the impression that he was in New York when his lordship—was removed. When Mr. Wooster informed your ladyship that his lordship had gone to Boston, he was relying on the version I had given him of his lordship’s movements. Mr. Wooster was away, visiting a friend in the country, at the time, and knew nothing of the matter till your ladyship informed him.”

Lady Malvern gave a kind of grunt. It didn’t rattle Jeeves.

“I feared Mr. Wooster might be disturbed if he knew the truth, as he is so attached to his lordship and has taken such pains to look after him, so I took the liberty of telling him that his lordship had gone away for a visit. It might have been hard for Mr. Wooster to believe that his lordship had gone to prison voluntarily and from the best motives, but your ladyship, knowing him better, will readily understand.”

“What!” Lady Malvern goggled at him. “Did you say that Lord Pershore went to prison voluntarily?”

“If I might explain, your ladyship. I think that your ladyship’s parting words made a deep impression on his lordship. I have frequently heard him speak to Mr. Wooster of his desire to do something to follow your ladyship’s instructions and collect material for your ladyship’s book on

Comments (0)