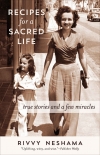

Recipes for a Sacred Life: True Stories and a Few Miracles Rivvy Neshama (best short books to read .TXT) 📖

- Author: Rivvy Neshama

Book online «Recipes for a Sacred Life: True Stories and a Few Miracles Rivvy Neshama (best short books to read .TXT) 📖». Author Rivvy Neshama

She arrived in a white taxi and stepped out holding her bag. John and I ran to greet her. Then the taxi driver got out and walked toward us, offering his hand. “Juan,” he said with a big warm smile. We all shook hands. I thought he would say more or give us his card, but that was it, and he drove away.

That’s when Gwen told us she had kept the driver waiting twenty minutes when he picked her up.

“I apologized to him several times,” she said. “He was nervous because he had another pickup to do right after me.”

She paused and then added, “What a nice man. He was worried and rushed, yet he still took time to meet you, a minute to connect.”

YOUNG BABES AND OLD BROADS

Most of us spend time with people our age. Here’s what can happen when you don’t.

YOUNG BABES

It was Christmas week, which explained it: John and I were stuck for hours in an endless line at customs in Gatwick Airport, London. We were lost in a mass of families, most of them Muslim. The women were wearing black or white hijabs, scarves that covered their hair and neck, and holding onto their children, who looked tired and cranky.

I was feeling the same—and also nervous, since this was the year of the shoe bomber and other plots by Islamic extremists. In fact, I was about to succumb to a very dark mood when I spotted in front of us a little Pakistani boy propped on his mother’s back and crying. He looked about two years old and was surrounded by family members; but none were paying him attention as they, too, looked ready to cry.

So I stepped into my best routine: hiding. I ducked behind John’s back and then popped my head above his right shoulder with a big smile and a “boo!” Then I hid again, this time appearing above John’s left shoulder. Well, I got the baby’s attention, and before long he stopped crying. In fact, he started to smile and soon was chortling. Cool, I thought, we’re playing peek-a-boo in Pakistani!

Then his young mother turned around, and she smiled too. She spoke to others who were with her, and they nodded at me as I nodded back.

In that moment, in that interminable line at that crowded airport, I felt happy: connected to a whole group of people I had stopped seeing as “family” and to this sweet baby boy who helped make me see.

HUM

One winter, John went to Africa, to a rural village in Mali. A European company was celebrating its centennial there by helping the villagers plant trees—one million trees—and John was invited to cover the story.

To launch the project, there was an outdoor ceremony near the pond, and every tribal chief and elder was present. After listening to four chiefs speak, and spotting five others lined up to follow, John drifted away to view a mud-built, castle-like mosque near the arc of huts where most people lived.

Soon after he started walking, John felt something warm and gentle in his hand. Looking down, he saw a young, barefoot boy, who held tightly onto his hand and smiled. John pointed to himself and said “John.” Then he pointed to the little boy, who said “Hum.”

And for the next two hours, wherever John went, Hum went, never letting go of his hand. They wandered through the village, into the school, and even planted a tree together and named it “Hum John.”

“He had such trust,” John later told me. “I think it’s because of the village. It felt so open and safe, as if all the adults were there for all the children.” I remembered the African saying “It takes a village to raise a child.”

John was moved by the warmth of the Mali people, by their music and their easy smiles. But what he’ll never forget is Hum, the little boy who took his hand.

TWENTY-SOMETHING

Another good thing about mixing the ages is it keeps you in tune with the changing times and expressions. I had a twenty-something guitar teacher named Dylan, who would always say to me, “No worries.”

Whenever I changed our appointment, whenever I forgot what he taught me, whenever I did anything wrong, that’s what he said: “No worries.”

It’s a kind phrase, I think, and reassuring. It makes me feel good about this new generation.

“But Dylan,” I told him one day, “I’m Jewish, I worry!”

He smiled at me and said, “No worries.” And now I’m saying it too.

VISITING OUR ELDERS

Visiting our elders is a mitzvah (see “Mitzvah” recipe). It’s one of those things I feel I’m meant to do, and it’s what I hope others will feel they’re meant to do when I’m older. It’s also, almost always, a source of joy: There’s the joy you give them, and the joy you feel seeing their joy, and the joy they give you with their stories and inspiration.

Now, some elders are more fun than others. So it goes. Katherine, a ninety-something neighbor, wasn’t a great talker, which meant it was sometimes a strain to keep the conversation going. If I asked her what was happening, she usually told me about her back pain.

Not a great topic. But we all need someone to complain to, right? So I would take off my sweater and listen.

The reason I took off my sweater was because Katherine, like many older people, kept the thermostat at about eighty-five degrees, winter and summer, which made her house as warm as Miami and also made me sleepy. But she was my next-door neighbor, so I tried to visit once a week. I mean, imagine what it’s like to live alone when you’re old and don’t get out much or have many friends still alive, so you just sit there most of the time, watching television. You’d welcome

Comments (0)