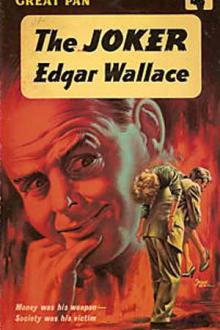

The Joker by Edgar Wallace (books to read in your 20s .TXT) 📖

- Author: Edgar Wallace

- Performer: -

Book online «The Joker by Edgar Wallace (books to read in your 20s .TXT) 📖». Author Edgar Wallace

The chauffeur uttered a tut of impatience. ‘Go ahead, Bluebeard!’ he

said.

Apparently one hundred and forty pounds of femininity was not too great a

tax on the chauffeur’s strength, for as he walked behind the weeping

little man, one hand on the scruff of his collar, he was whistling softly

to himself.

Up the stone steps he walked and into the hall. The ancient maid came

peeping round the corner, and almost fell down the kitchen stairs in her

excitement, for something was happening at Royalton House—where nothing

had happened before.

The chauffeur lowered the girl into a little armchair. Her eyes were

open; she was feeling deathly ill.

‘There is nothing in the world like a cup of tea,’ suggested the

chauffeur, and called in the maid, so imperiously that she never even

glanced at her master. He seemed dwindled in stature. In his hand he

still held the wet haft of the axe.

He was rather a pathetic little man.

‘I think you had better put that axe away,’ said the chauffeur gently.

Aileen only then became aware of his presence. He had a funny moustache,

walrus-like and black, and as he spoke it waggled up and down. She wanted

to laugh, but she knew that laughter was halfway to hysteria. Her eyes

wandered to the axe; a cruel-looking axe—the handle was all wet and

slippery. With a shiver she returned her attention to the chauffeur; he

was holding forth in an oracular manner that reminded her of somebody.

She discovered that he was watching her too, and this made her uneasy.

‘You’ve got to help me, young lady,’ said the man gravely.

She nodded. She was quite willing to help him, realising that she would

not be alive at that moment but for him.

The chauffeur rolled his eyes round to Ellenbury.

‘O, what a tangled web we weave, When first we practise to deceive!’ he

said reproachfully; and stripped his black moustache with a grimace of

pain.

‘Thank God that’s gone!’ he said, and pulled up a chair to the fire. ‘I

was once very useful to Nova—Nova has this day paid his debt and lost a

client. Why don’t you take off your overcoat? It’s steaming.’

He glanced at the axe, its wet haft leaning against the fireplace and

then, reaching out his hand, took it on to his knees and felt its edge.

‘Not very sharp, but horribly efficient,’ he said, and laid his hand on

the shoulder of the shrinking man. ‘Ellenbury, my man, you’ve been

dreaming!’ Ellenbury said nothing. ‘Nasty dreams, eh? My fault. I had you

tensed up—I should have let you down months ago.’

Now Ellenbury spoke in a whisper.

‘You’re Harlow?’

‘I’m Harlow, yes.’ He scarcely gave any attention to the two suitcases;

one glance, and he did not look at them again. ‘Harlow the Splendid. The

Robber Baron of Park Lane. There’s a good title for you if you ever write

that biography of mine!’

Mr Harlow glanced round at the girl and smiled; it was a very friendly

smile.

Ellenbury offered no resistance when the big man relieved him of his wet

coat and held up the dressing-gown invitingly. ‘Take off your shoes.’ The

old man obeyed; he always obeyed Harlow. ‘When are you leaving?’

‘Tomorrow,’ The admission was wrung from him. He had no resistance.

‘One suitcase full of money is enough for any man,’ said Harlow. ‘I’ll

take a chance—you shall have first pick.’

‘It’s yours!’ Ellenbury almost shouted the words.

‘No—anybody’s. Money belongs to the man who has it. That is my

pernicious doctrine-you will go to Switzerland, get as high up the

mountains as you can. St Moritz is a good place. Very likely you’re mad.

I think you are. But madness cannot be cured by daily association with

other madmen. It would be stupid to hide you up in an asylum—stupid and

wicked. And if you will not think of killing people any more, Ellenbury.

You—are—not—to—think—about—killing!’

‘No!’ The old man was weeping foolishly.

‘Our friend Ingle leaves for the Continent tomorrow—join him. If he

starts talking politics, pull the alarm cord and have him arrested. I

don’t know where he is going—anywhere but Russia, I guess… ‘

All the time he was talking, Aileen sensed his anxiety. Just then the

maid brought in the tea and the big fellow relaxed.

‘Drink that hot,’ he ordered, and when the servant had gone he moved

nearer to the girl and lowered his voice. ‘He doesn’t respond. You

noticed that? No reflexes, I’m certain. I dare not try; he’d think I was

assaulting him. It was my own fault. I kept him too tense—too keyed up.

If I had let him down… umph!’ He shook his head; the thick lips pursed

and drooped. Presently he spoke again. ‘I’ll have to bring you both

away—you can be very helpful. If you insist upon going to Carlton and

telling him about… this’—he nodded to the unconscious man by the

fire—‘I shan’t stop you. This is the finish, anyway.’

‘Of what?’ she asked.

‘Harlow the Joker,’ he said. ‘Don’t you see that? Here’s a man who tried

to murder you—a madman. Why? Because he thought you knew he was bolting.

Here’s Harlow the magnificent masquerading like a fiction detective with

a comic moustache! Why? Imagine the police asking all these questions.

And Ellenbury of course would tell them quite a lot of things—some

silly, some sane. The police are rather clever—not very, but rather.

They’d smell—all sorts of jokes. I want a day if I can get it. Would you

come to Park Lane for a day?’

‘Willingly!’ she said; and he went red.

‘That is a million-pound compliment,’ he said. ‘You’ll have to sit on the

floor with a rug over you; you mustn’t be seen. As it is, if you are

missed, your impetuous lover—did you speak?’

‘I didn’t,’ she said emphatically.

‘If he learns that you have disappeared, my twenty-four hours will be

shortened.’

She glanced at Ellenbury. ‘What shall you do with… him?’ she asked.

‘He sits by my side; I dare not leave him here.’ He lifted up one of the

suitcases and weighed it in his hand. ‘Would you like half a million?’ he

asked pleasantly.

Aileen shook her head. ‘I don’t think there is much happiness in that

money,’ she said.

He laughed. ‘Forgive me! I’ve got a little joke at the back of my

mind—maybe I’ll tell you all about it!’

SHE TOLD Jim all about this as he drove her back to her rooms after she

had brought a policeman to release him.

‘He IS rather a darling,’ she repeated, and when he frowned she pressed

his arm and laughed. ‘Somehow I don’t think you will arrest him,’ she

said. ‘But if you do, hold him very tight!’

And she thought of Mr Harlow’s joke.

When, an hour later, a strong force of plain-clothes policemen descended

upon 704 Park Lane, they found only Mrs Edwins, erect and intractable as

ever, her hands folded over her waist.

‘Mr Harlow left for the country this morning,’ she said, and when they

searched the house they discovered neither the Splendid Harlow nor the

golden-bearded man called Marling.

‘Arrest me!’ she sneered. ‘It takes a clever policeman to arrest an old

woman. But you’ll not take Lemuel.’

‘Lemuel?’

She realised her mistake.

‘I called him Lemuel when he was a child, and I call him Lemuel now,’ she

said defiantly. ‘He’ll ruin every one of you—mark my words!’

She was still muttering threats when two detectives found her coat and

hat and led her, protesting, to the police station.

Mr Harlow’s landed possessions were not limited to his pied-a-terre in

Park Lane. He had a large estate in Hampshire, which he seldom visited,

though he retained a considerable staff for its upkeep. It was known that

he owned a luxurious flat in Brighton; and it was generally believed that

somewhere in London he kept another extensive suite of apartments.

Stratford Harlow was a far-thinker. He saw not only tomorrow but the day

after. For over twenty years he had lived in the knowledge that he was a

reprehensible jester, and that there was always a possibility, if not a

probability, that his supreme ‘joke’ would be detected.

He was at the mercy of many men, for only the mean thief may work

single-handed. He had perforce to employ people who must be taken—a

little—into his confidence.

But only one person knew the big truth.

His chauffeur, who knew so much, never dreamt the whole; to Ellenbury he

had been a crooked market-rigger; to Ingle he had been an admirable enemy

of society. To himself, what was he? That ‘joke’ idea persisted; almost

the description fitted his every action. When he had locked the grille on

Jim he knew that the ‘joke’ was on him. The machinery of the law had

begun to move, and there was nothing to be gained by dodging from one

hiding place to another. It was a case of night or nothing.

He went to the foot of the stairs and whistled; and soon Mrs Edwins came

into view with the tall, bearded man.

‘Marling, I am going to take you for a little drive,’ said Stratford

Harlow pleasantly. ‘You are at once a problem and a straw. You have

almost broken my neck and I am grasping at you.’ He laughed gently.

‘That’s a mixed illustration, isn’t it?’

‘Where are you going?’ asked Mrs Edwins.

He fixed her with his cold eyes.

‘You are very inquisitive and very stupid,’ he said. ‘What is worse, you

lack self-control, and that has nearly been my undoing. Not that I blame

you.’ A gesture of his white hand absolved her from responsibility.

‘Telephone to Reiss to bring the car. Possibly he will telephone in reply

that he is unable to bring the car. You may even hear the strange and

authoritative voice of a policeman.’

Her jaw dropped.

‘You don’t mean?’ she asked quickly.

‘Please telephone.’

He was very patient and cheerful. He did not look at her; his eyes, lit

with a glint of humour, focused upon the uncomfortable man who faced him.

‘I hope I’ve done nothing—’ began Marling.

‘Nothing at all—nothing!’ said Mr Harlow with the greatest heartiness.

‘I have told you before, and I tell you again, you have nothing to fear

from me. You are a victim of circumstances, incapable of a wrong action.

I would sooner die than that you suffered so much as a hurt! Injustice

pains me. That variety of justice which is usually called “poetical”

fills me with a deep and abiding peace of soul. Well?’ He snapped the

question at the woman in the doorway.

‘What am I to do with that girl?’ she asked.

‘Leave her alone,’ said the big man testily, ‘and at the earliest

opportunity restore her to her friends. Help Mr Marling on with his coat;

it is a cold night. And a scarf for his throat… Good!’

He peered through the ground-glass window.

‘Reiss has brought the car. Trustworthy fellow,’ he said, and beckoned

Marling to him. Together they left the house and were driven rapidly

away. For nearly a quarter of an hour Mrs Edwins stood in the deserted

vestibule, very upright, very forbidding, her gnarled hands folded,

staring at the door through which they had passed.

The car drove through Mayfair, turned into a side street and stopped. It

was a corner block, the lower floor occupied by a

Comments (0)