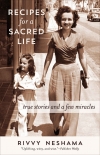

Recipes for a Sacred Life: True Stories and a Few Miracles Rivvy Neshama (best short books to read .TXT) 📖

- Author: Rivvy Neshama

Book online «Recipes for a Sacred Life: True Stories and a Few Miracles Rivvy Neshama (best short books to read .TXT) 📖». Author Rivvy Neshama

What I noticed was I judge almost always, and I didn’t know how to stop. I judge myself, I judge others, I judge myself for judging others. I judge friends, strangers, events. I judge neighbors, politicians, the weather . . . I’m an all-inclusive judge!

This was not good news. I wanted to move on to the second law, and the third, and fourth . . . and live a life of Harmony, Success, and Miracles. But I felt I couldn’t read further until I had the first law down cold. Otherwise, it would feel like cheating. Besides, it probably wouldn’t work.

So I kept rereading chapter 1. Then I would meditate, be silent, look at the birds . . . and watch myself judge. It was hopeless, and so was I.

It reminded me of the salsa class John and I took one winter. Our teacher, Carmen, made the lessons so easy that within a few weeks we were moving our hips, getting the rhythm, and feeling, hey, we can do this. But in the last two sessions, Carmen taught turns, and try as we would, this was not meant to be. John would turn one way, I would turn the other, and we’d never end up in the same place at the same time.

The next month, Carmen offered Level 2 classes, but knowing our problem with turns, we signed up for another go at Level 1. This worked out well. We got even better at the basics. So good, in fact, that Carmen said “Watch John and Rivvy” and made us dance at the front of the room. Our classmates were impressed with our style and savvy—until session five, when Carmen again taught turns. Well, I thought, we could just keep signing up for Level 1 and have a few weeks of glory.

With that same reasoning, I decided I could make Deepak’s first law my life’s practice. And then, one day, while yet again reading chapter 1, I noticed something he wrote that I must have skimmed over before. If a whole day of non-judging seems too daunting, he says, start smaller. Say something like “For the next two hours, I won’t judge at all.” Or lower the bar even more: “Just this hour, I will not judge.”

This sounded doable, and indeed, I could do it! For one hour, I would notice my judging, let it go, and move on. And as I stopped judging, I began to feel a wonderful lightness, a sense that everything, including myself, was okay.

At last, I was ready to move on to chapter 2, “The Law of Giving,” and step up my spiritual life. But the funny thing is, I’m still reading chapter 1, over and over, and practicing “The Law of Pure Potentiality.” It’s the basics, the footwork, the where to begin—just like Carmen’s first class got us out there and dancing.

GRATEFUL IN HARLEM

I don’t always feel that grateful. Sometimes, when things are really bad, I don’t even try. But then I remember the darkest time of my life, and meeting Billie, and learning the power of being grateful.

My first marriage, to the man I thought was my soul mate, had ended. We parted, he found a new place, and our two young children, Tony and Elise, moved back and forth between us, clutching their overnight bags and looking as confused and fragile as we were.

It wasn’t long after then that I began to have panic attacks. I didn’t know that’s what they were called. I only knew I couldn’t breathe and thought I was dying or going crazy. Night after night, I sat up in bed, praying for sleep or to make it through.

Most of all, I prayed for salvation. And it came through two things: my job and my children. They made me get up and keep moving; they gave me a purpose and a life.

The job was in Harlem. I was a community organizer helping school kids at risk. A team of us worked out of a church, and we were a motley crew: one ex-debutante, two guys from the ’hood, one church lady, and me—white girl with good intentions.

The men were a lively pair, always slapping each other and giving high fives. They seemed to bop more than walk, and their talk was fast and fluid. But what I liked most about them was they were real—no fake smiles, no pretense at all—and I found that comforting. They didn’t hide their pain: I saw it in their faces. I even saw it sometimes in the face of our boss, the activist reverend Dr. C. I once asked Dr. C how he was doing and he said, “I’m hangin’ in, honey, hangin’ in by a thread.”

The one who helped hold us up was the church lady, Billie, a handsome, hearty black woman whose humor was sharp but softened by her smile. She was my first live church lady, full of faith, and her own calm center helped me feel anchored and safe. And then there were her cakes, baked from scratch, awesome cakes with lemon icing that she’d bring to the church.

One day Billie found me crying and asked, “What’s wrong, child?”

What’s wrong seemed beyond words. I was lost, frightened, and deeply depressed. With my soul mate gone, I forgot who I was, and each day was a battle against my own pain.

What made the pain worse was that it felt unworthy, compared to what I saw daily in Harlem: junkies falling in slow motion on sidewalks, and young kids killing themselves or others.

“Your pain is your pain,” Billie said softly. “We’ve all got our struggle. But what you need, child, is to practice some gratefulness.” Then she gave me this recipe to help me begin.

Billie told me to get a journal and write down each night—free form, no thinking—two lists, as long as I could

Comments (0)