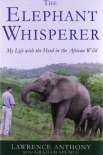

The Elephant Whisperer: My Life With the Herd in the African Wild Lawrence Anthony (speld decodable readers txt) 📖

- Author: Lawrence Anthony

Book online «The Elephant Whisperer: My Life With the Herd in the African Wild Lawrence Anthony (speld decodable readers txt) 📖». Author Lawrence Anthony

Fortunately Françoise was there and took over. She did so reluctantly as rural Zulu society is polygamous and uncompromisingly masculine. No man wants to be seen listening to a woman.

Chauvinism? Sure, but that’s the way it is out in the sticks. It took skill and charm for Françoise to hold her ground. Eventually the chief relented, admitting he had no real concerns.

With approval from the amakhosi secured, we selected seventy of the fittest-looking recruits and in record time were up and running. Singing ancient martial songs, the Zulu gangs started work and despite the impossible deadline, as the fence slowly crept across the countryside, I began to breathe easier.

Then just as we started to see progress we ran up against a wall.

David came sprinting into the office. ‘Bad news, boss. Workers on the western boundary have downed tools. They say they’re being shot at. Everyone’s too scared to work.’

I stared at him, uncomprehendingly. ‘What do you mean? Why would anyone shoot at a gang of labourers?

David shrugged. ‘I dunno, boss. Sounds like it has to be a cover for something else, perhaps a strike for more money …’

I doubted that, as the workers were paid a decent rate already. The reason for the strike was more likely to be muthi, or witchcraft.

In rural Zululand belief in the supernatural is as commonas breathing, and muthi is all-powerful. It can either be benevolent or malevolent, just as sangomas – witchdoctors – can be both good and evil. To resist bad muthi you need to get a benign sangoma to cast a more potent counter spell. Sangomas charge for their services, of course, and sometimes initiate stories of malevolent muthi for exactly that purpose – and that’s what could be happening here.

‘What do we do, boss?’

‘Let’s try and find out what’s going on. In the meantime we don’t have much choice. Pay off those too spooked to work and let’s get replacements. We’ve got to keep moving.’

I also gave instructions for a group of security guards to be placed on standby to protect the remaining labourers.

The next morning David once more came running into the office.

‘Man, we’ve got real problems,’ he said, catching his breath. ‘They’re shooting again and one of the workers is down.’

I grabbed my old Lee – Enfield .303 rifle and the two of us sped to the fence in the Land Rover. Most of the labourers were crouching behind trees while a couple tended to their bleeding colleague. He had been hit in the face by heavy shotgun pellets.

After checking that the injury was not life-threatening, we started criss-crossing the bush until we picked up the tracks – or spoor as it is called in Africa. It belonged to a single gunman – not a group, as we had initially feared. I called Bheki and my security induna Ngwenya, whose name means crocodile in Zulu, two of our best and toughest Zulu rangers. Bheki is the hardest man I have ever met, slim with quiet eyes and a disarmingly innocent face, while Ngwenya, thickset and muscular, had an aura of quiet authority about him which influenced the rest of the rangers in his team.

‘You two go ahead and track the gunman. David and I will stay here to protect the rest of the workers.’

They nodded and inched their way through the thornveld until they believed they were behind the shooter. They slowly cut back and waited … and waited.

Then Ngwenya saw a brief glint of sunlight flash off metal. He signalled to Bheki, pointing to the sniper’s position. Lying low in the long grass, they rattled off a volley of warning shots. The sniper dived behind an anthill, fired two blasts from his shotgun, then disappeared into the thick bush.

But the guards had seen him – and to their surprise, they knew him. He was a ‘hunter’ from another Zulu village some miles away.

We drove the shot labourer to hospital and called the police. The guards identified the gunman and the cops raided his thatched hut, seizing a dilapidated shotgun. Amazingly, he confessed without any hint of shame that he was a ‘professional poacher’ – and then heaped the blame on us, saying that erecting an electric fence would deprive him of his livelihood. He no longer could break into Thula Thula so easily. He denied trying to kill anyone, he just wanted to scare the workers off and stop the fence being built. Not surprisingly, that didn’t cut much ice with the authorities.

I asked to see the shotgun and the cops obliged. It was a battered double-barrel 12-bore, as ancient as its owner. The stock, held together with vinyl electrical tape, was scratched and chipped from thousands of scrapes in the bush. The barrel was rusted and pitted. There was no way this was the person responsible for our major poaching problem.

So who was?

With that disruption behind us the construction continued from dawn to dusk, seven days a week. It was back-breaking work, sweaty and dirty with temperatures soaring to 110 degrees Fahrenheit. But mile by torturous mile, the electric fence started to take shape, inching northwards, then cuttingeast and gathering momentum as the workers’ competency levels increased.

Building a boma was equally gruelling, albeit on a far smaller scale. We measured out 110 square yards of virgin bush and cemented 9-foot-tall, heavy-duty eucalyptus poles into concrete foundations every 12 yards. Then coils of tempered mesh and a trio of cables as thick as a man’s thumb were strung onto the poles, tensioned by the simple expedient of attaching the ends to the Land Rover bumper and ‘revving’ it taut.

But no matter how thick the cables, no bush fence will hold a determined elephant. So the trump card is the ‘hot wires’. The electrification process is deceptively simple. All it consists of is four live wires bracketed onto the poles so they run inside the structure, while two

Comments (0)