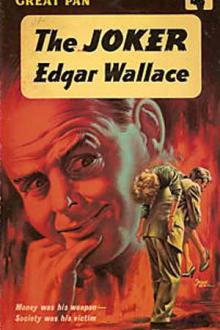

The Joker by Edgar Wallace (books to read in your 20s .TXT) 📖

- Author: Edgar Wallace

- Performer: -

Book online «The Joker by Edgar Wallace (books to read in your 20s .TXT) 📖». Author Edgar Wallace

things that may not be written about… he could not think back without

feeling physically sick. In truth he would not have stretched out his

hand if, by so doing, he could have opened those cell doors and released

to the world the social sweepings whom it was his professed mission to

salve.

His work finished, he lit a cigarette, fitted it carefully into an amber

holder and, adjusting the cushions, lay down on the settee and smoked and

thought till the telephone bell roused him and he got up.

The voice that spoke to him was quite unfamiliar. ‘Is that Mr Ingle?’

‘Yes,’ he said shortly.

‘Will you make a sacrifice of your principles?’ was the astonishing

request, and the man smiled sourly.

‘What I have left, yes. What do you wish?’

It might be an old friend in need of money, in which case the

conversation would be short. For Arthur Ingle had no foolish ideas about

charity.

‘Could you meet me tonight on the sidewalk immediately opposite Horse

Guards Parade?’

‘In the park, you mean?’ asked Ingle, astonished. ‘Who are you? I’ll tell

you before you go any further that I’m not inclined to go out of my way

to meet strangers. I’m a pretty tired man tonight.’

‘My name is—’ a pause—‘Harlow.’

Involuntarily, Ingle uttered an exclamation.

‘Stratford Harlow?’ he asked incredulously.

‘Yes, Stratford Harlow.’

There was a long pause before Arthur Ingle spoke. ‘It’s rather an

extraordinary request, but I realise that it isn’t an idle one. How do I

know you’re Harlow?’

‘Call me up in ten minutes at my house and ask for me,’ said the voice.

‘Will you come?’

Again Mr Ingle hesitated. ‘Yes, I’ll come,’ he said. ‘At what time?’

‘At ten o’clock exactly. I won’t keep you hanging about this cold night.

You can get into my car and we’ll drive somewhere.’

Ingle hung up the telephone a little bewildered. He was a cautious man

and after ten minutes had expired he put through the number he discovered

in the phone directory, and the same voice answered him. ‘Are you

satisfied?’

‘Yes, I’ll be there—ten o’clock,’ he said.

He had two hours to wait. The charwoman did not arrive till nine. He gave

her instructions, made arrangements for the following day; and went back

to the dining-room to think out the extraordinary request which Stratford

Harlow had made of him. And the more he thought, the less inclined he as

to keep the appointment. At last he turned to his writing table, took out

a sheet of paper and scrawled a note.

“DEAR MR HARLOW,

“I am afraid I must disappoint you. I am in such a position, being an

ex-convict, that I cannot afford to take the slightest risk. I will tell

you I frankly that what I have in my mind is that this may be a frame-up

organised by my friends the police, and I think that it would be, to say

the least, foolish on my part to go any farther until I know your

requirements, or at least have written proof that you have approached me.

“Yours sincerely,

“ARTHUR INGLE.”

He put the letter in an envelope, addressed it, and marked in the corner

in bold letters ‘By hand. Urgent.’ Even now he was not satisfied. He went

to the telephone to call a district messenger, but he did not lift the

receiver. His curiosity was piqued. He felt he must know, with the least

possible delay, just why Stratford Harlow had summoned Arthur Ingle, late

of Dartmoor convict establishment. And why should the meeting be secret?

A man of Harlow’s standing would not lose caste, even if he sent for him

to go to his house. He came to a sudden resolve, pitched the letter on to

the table, went into his bedroom and changed into a dark suit.

By the time he had climbed into his overcoat he was satisfied that he was

taking the wisest course. The charwoman was in the kitchen and he opened

the door to pass his last admonition. She was on her knees,

scrubbing-brush in hand, and he looked down into a long, weak face over

which strayed lank wisps of grey-black hair.

‘I’m going out. You needn’t wait. Finish your work and be here in the

morning before eight,’ he barked and slammed the door on this

inconsiderable member of the proletariat and went down the stairs in a

spirit of adventure that made him feel almost young.

As the Horse Guards clock was chiming the three-quarters he came into

Birdcage Walk and turned along the lonely footpath that runs parallel

with the House Guards and flanks the broad parade ground. There was no

hurry; he fell into a gentle stroll, fast enough to keep him warm and to

avoid any suspicion of loitering within the meaning of the act.

It could not be a frame-up, he had decided. A man of Harlow’s character

would hardly lend himself to such a plot; and in his heart of hearts, for

all his bitter gibes at the police, he did not believe seriously in the

prison legend of innocent men being trapped by cunning police plots.

He looked at his watch under a street standard; it was five minutes to

ten, and he strolled back the way he had come, and stopped immediately in

a line with the gates that closed the arch of the Horse Guards. As he did

so a car came noiselessly along the sidewalk from the direction of

Westminster.

It stopped in front of him and the door opened.

‘Will you come in, Mr Ingle?’ said a low voice; and without a word he

stepped inside, pulling the door close after him and sank down on a soft

seat by the side of a man who, he at once recognised, was that Splendid

Harlow, whose name, even in Dartmoor, symbolised wealth beyond dreams.

The car, gathering speed, turned into the Mall, swung round towards

Buckingham Palace and across the Corner into Hyde Park. It slackened

speed now, and Stratford Harlow began to talk…

For an hour the car moved at a leisurely pace round the Circle. Sleet was

falling. Ingle listened like a man in a dream to the amazing proposition

which his companion advanced.

He, at any rate, sat in comfort. Inspector Jim Carlton, following in an

aged convertible was chilled and wet, and the highly sensitive microphone

which he had placed in Harlow’s car failed to transmit the talk it was so

vital he should hear.

Arthur Ingle arrived home at his flat soon after eleven. The cleaner had

gone and he was glad; dull clod and unimaginative as she was she yet

might have read and interpreted the light that shone in his eyes or have

sensed the exultation of his heart.

Brewing himself some coffee, he sat down at his desk and in to make

notes. Once he rose and, entering his bedroom, turned on the light above

his dressing-table and stared at himself for five minutes in the glass.

The scrutiny seemed to afford him a certain amount of satisfaction, for

he; smiled and returned to his notemaking.

That smile did not leave his lips; and once he laughed out loud.

Evidently something had happened that afforded him the most exquisite

happiness.

‘Could you please come and see me in the lunch hour?—A.R.’

JIM CARLTON looked at the ‘A.R.’ blankly before he placed ‘A’ as

indicating Aileen—he was under the impression that she spelt her name

with an ‘E’. It had been delivered at Scotland Yard by a messenger half

an hour before he arrived. Literally he was waiting on the mat when she

came out; and she seemed very glad to see him.

‘You will probably be very angry that I’ve sent for you about such a

little thing,’ she said, ‘and you’re so busy—’

‘I won’t tell you how I feel about it,’ he interrupted, ‘or you’ll think

I’m not sincere.’

‘You see, you are the only policeman I know and I don’t know you very

well, but I thought you wouldn’t mind. Mrs Gibbins has disappeared; she

didn’t go home last night nor the night before.’

‘I’m thrilled,’ he said. ‘And her husband fears the worst?’

‘She hasn’t a husband; she’s a widow. Her landlady came in to see me this

morning. She’s dreadfully upset.’

‘But who’s Mrs Gibbins?’

‘Mrs Gibbins is the charwoman at Uncle’s flat. Rather a wretched-looking

lady with untidy hair. I’m rather worried about it because she’s a woman

without friends. I called up my Uncle’s flat this morning and he was

almost polite, and told me that she didn’t arrive yesterday morning and

she hasn’t been there today.’

‘She may have met with an accident,’ was his natural suggestion.

‘I’ve telephoned to the big hospitals, but nothing has been heard of her.

I want you to tell me what I can do next. It’s such a little matter that

I’ll listen meekly to any rude comment you care to think up!’

He was not interested in Mrs Gibbins; the case of a lonely woman who

disappears as from the face of the earth was so common a phenomenon in

the life of any great city that he could hardly work up enthusiasm for

the search. But Aileen was so concerned that he would have been a brute

to have treated her request lightly; and after lunch, the day being his

own, he went to Stanmore Rents in Lambeth, a little riverside slum and

made a few inquiries at first hand.

Mrs Gibbins had lived there, the slatternly landlady told him, for five

years. She was a good, sober, honest woman, never went out, had no

friends, and subsisted on what she earned and a pound a week which was

paid to her quarterly by some distant relation. In fact, she was due to

receive the money on the following Monday. Her chief virtue was that she

paid her rent every Monday morning and gave no trouble.

‘Do you mind if I search her room?’

The landlady wished that and showed him the way; it gave her a nice

feeling of authority to be present during the operation.

Jim was shown into a small back room, scrupulously clean, with a bed and

a sort of home-made hanging cupboard that had been fixed in one corner

and was shrouded by a cheap curtain. Here was the meagre wardrobe of the

missing charwoman: a skirt or two, a light summer coat that had seen its

brightest days, and a best hat. He tried the chest of drawers and found

one drawer locked. This he opened with the first key on his own bunch, to

the awe and admiration of the landlady. Here was proof of the woman’s

affluence—a post office bank-book showing �87 to her credit, four new �1

Treasury notes, and a threadbare bag with a broken catch.

Inside this were one or two proofs of the vanity of the eternal

feminine—a greasy powder-puff, a cheap trinket or two, and between

lining and outer cover a folded paper of some sort.

It had not got there by accident, he saw, when he carried the bag to the

light, for it was carefully sewn into the lining. He took out his pocket

knife and, picking the stitches, extracted what he thought was one sheet

of paper, lightly folded. When he opened the paper out he found there

were two sheets.

The landlady ducked her head sideways in an effort to catch a glimpse of

the writing, but Jim was aware of this manoeuvre.

Comments (0)